Lebanon: Cholera cases soar with refugee camp in north at centre of outbreak

Lebanon’s first cholera outbreak in 30 years is spreading across the country, with health officials fearing that the serious and potentially fatal disease is being transmitted through contaminated food and water.

The Ministry of Health recorded 718 cases on Monday, including 287 confirmed cases within 24 hours, with 11 deaths.

The majority of cases were recorded in Akkar and Bekaa, two regions that host thousands of refugees from Syria - where a cholera outbreak is sweeping over cities such as Idleb and Aleppo.

But patients have also been hospitalised in the cities of Beirut and Tripoli, as well as most other regions in the country. Tests of water samples confirmed that cholera was present all over Lebanon, according to the World Health Organisation.

According to a local official and medic, Lebanon’s northernmost region Akkar - which is also its poorest - is at the centre of the outbreak.

“In Bebnine alone, we’re recording 200 cases a day,” Kifah el-Kasser, the city’s mayor and a doctor at the al-Iman health centre, told Middle East Eye.

He warned that actual contaminations may be much higher than health ministry numbers.

“Last week alone, we treated 1,200 patients,” Kasser said.

According to his estimates, Lebanon may have recorded thousands of cases nationwide, by far exceeding official counts.

Similar patterns have also been seen in Halba, Akkar’s only government hospital, with 120 patients treated there on Saturday alone.

“Our services are very stretched, and we have to increase our capacity quickly to match the pace of contamination,” the hospital’s director, Mohammad Khadrine, told MEE.

The emergency services are under severe pressure as patients arrive in critical condition. Cholera causes acute diarrhoea and vomiting, with patients quickly becoming dehydrated. Without treatment, patients can lose up to 50 percent of bodily fluids and die within a few hours.

'Death's door'

On the first floor of the Halba hospital, men, women, and children filled the beds.

“My daughter was at death's door, her skin had changed colour and her eyes had sunk into their pockets,” Qyada Ahmad Murrha, a Lebanese citizen originally from Bebnine, told MEE.

Luckily, a simple IV drip with a rehydration solution usually helps patients heal quickly.

“Most severe cases can leave the hospital after a few hours,” a nurse, who wished to remain anonymous, told MEE.

For two years, Lebanon has been gripped by the worst economic crisis in its history. Its healthcare system used to be among the best in the region, but is now struggling to keep up with successive epidemics.

Lebanon’s caretaker health minister, Firas Abiad, has visited Halba’s public hospital several times during the last few weeks.

“It is on the frontline,” he said during a press conference at the hospital on Saturday, promising vaccines for hospital staff and 5m chlorine tablets for the region so that residents could disinfect their drinking water. He also highlighted the "frightening decline" in the level of basic services in Akkar.

Of the 145 pumping stations in northern Lebanon, only 22 are running on electricity provided by the state, he said, with the rest either running on private fuel supplies or not running at all. All of Akkar's rivers are polluted by waste and sewage, providing an ideal environment for the spread of cholera, according to the WHO.

With the poverty rate at 92 percent, according to UN figures, Akkar has been largely abandoned by the state for decades, with development funding largely going to Beirut and the other large cities.

“There is only one hospital and one waste collection company. The roads are in bad shape and many people don’t have running water,” Nadine Sabah, founder of the Akkar Network for Development, a local NGO, told MEE.

“Some houses have only recently got electricity for the first time,” she added.

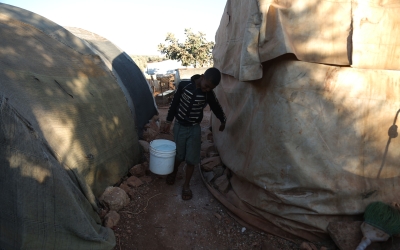

Refugee camps

In Syrian refugee camps, dilapidated sanitary conditions have led to infected sewage running into streams and contaminating neighbouring agricultural land.

“Our toilets are nothing more than a hole in the ground," said Hoda Ismail*, a Syrian woman originally from Qusayr who lives in one of Akkar’s refugee camps.

"When it rains, the sewage flows into the streets where our children play.”

'Our toilets are nothing more than a hole in the ground. When it rains, the sewage flows into the streets where our children play'

- Hoda Ismail*, Syrian refugee

In Bebnine’s Wadi Jamous neighbourhood, infections are being reported in nearly every family.

“All of my five children are sick, my wife too - and I just got better after a week of severe diarrhoea,” said Muhammad Awad Ibrahim, 62, also from Qusayr.

He said he could afford to pay for only one treatment, sending his wife to Halba’s hospital.

“I can barely pay the rent for my tent, so can you imagine all seven of us going to the doctor?” he said.

The government has pledged to pay for every Lebanese victim of cholera, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees covers the costs of treating Syrian nationals.

Yet, most patients MEE spoke to claimed they had been asked to pay for cholera tests or hospital admission.

“If you can’t pay, they’ll let you die at their doors,” Ismail said.

* Name changed by request

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].