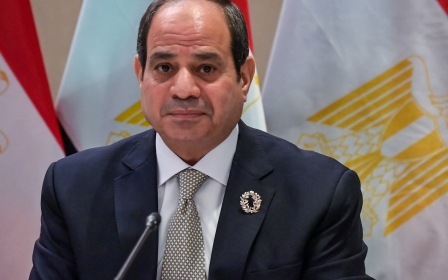

Egypt: How the military has usurped Sisi's power

This past April, during an event known as the Egyptian family iftar and in the presence of prominent opposition figures, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi announced the launch of a national dialogue process and a “presidential pardon committee”, sparking hopes for much-needed political and economic reforms that could ease the repression that has reigned for the better part of a decade.

Sisi’s announcement came amid a burgeoning economic crisis, which has seen the pound lose more than a third of its value this year, signalling the dire need for a shift away from the regime’s policy of debt-driven growth. Yet, more than six months later, no serious efforts towards reform appear to be underway.

This resistance to reform stems from a number of intertwined factors that have significantly weakened the presidency in Egypt

This can be attributed to structural constraints on the regime’s ability to initiate top-down reforms, the most notable of which is the weakness of the presidency vis-a-vis the military establishment and security services, which can act as a bulwark against reforms, regardless of the president’s intentions.

On the political front, the presidential pardon committee has been an abject failure. According to Amnesty International, 766 political prisoners were released between April and November - but over that same period, 1,540 more were arrested. This reflects the deepening of repression, a failure that might be partially attributed to the resistance of security services to release detainees, and the pardon committee’s lack of authority to make binding decisions.

In terms of resistance from security services, Kamal Abu Aita, a committee member and former labour minister, has voiced his frustration publicly on several occasions, citing open defiance of presidential release orders. In terms of institutional authority, the pardon committee collects the names of prisoners from family members and sends a list for potential release to security services to be approved over WhatsApp. The process remains extremely opaque, with no clear criteria for release.

Financing gap

On the economic front, resistance to possible reforms also became apparent during recent loan negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). On 27 October, the IMF announced that an initial agreement for a $3bn loan had been reached with the Egyptian regime, to be delivered over four years.

After the announcement was made, reports emerged that the regime had opted for a smaller loan amount, because a larger amount would have entailed more stringent conditions, chief among which was a reduction in the size of the military’s economic footprint and state intervention in the economy.

This decision seems counterintuitive, considering that the regime has an estimated $45bn financing gap. Indeed, Goldman Sachs has estimated that Egypt needs an IMF loan of at least $15bn to be able to cover its financing needs. Thus, the October announcement signals a strong commitment by the regime to continue its model of militarised capitalism, regardless of the accompanying economic crisis.

This resistance to reform stems from a number of intertwined factors that have significantly weakened the presidency in Egypt, robbing Sisi of the ability to balance conflicting forces. The clearest manifestation of this was the constitutional amendment of 2019, which vastly increased the power of the military establishment while weakening the presidency.

For example, Article 234 was changed to state that the defence minister could only be appointed after the approval of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. Effectively, that places the position beyond the president’s reach. In addition, an amendment to Article 200 notes that the military is responsible for protecting Egypt’s “constitution and democracy”, as well as the “basis and the secular nature of the state”. This further elevates the military to a paramount position above the president.

Escalating crises

The constitutional weakness of the presidency is compounded by the practical weakness of this position in terms of control over the state apparatus and a lack of civilian counterbalance. The state apparatus is heavily populated by retired members of the armed forces, not only at the highest levels of bureaucracy, but also at lower levels of local government and the public sector.

This phenomenon is not new, as it was part of a coup-proofing strategy under former President Hosni Mubarak - but unlike Mubarak, Sisi does not have a massive civilian ruling party that he can use to balance the military. Indeed, there is no evidence that the pro-Sisi majority party in parliament, Mostqabal Watan, plays an effective role in policymaking, nor does it appear to occupy any key government positions.

There is even evidence that the trend towards militarising local government has increased with a legal amendment in July 2020, which stipulates that each governorate should have a military adviser who acts as a local representative of the defence minister, liaising with the local community to solve problems. In essence, the state bureaucracy has fallen deeper into the clutches of the military establishment.

The regime that has evolved out of the 2013 coup is a military dictatorship par excellence. The position of the presidency has been weakened to such an extent that one would struggle to imagine a situation where the president could act against the interests of the military establishment without suffering severe consequences.

This is not to argue that the president is powerless, but the process of consolidating power and inoculating against popular pressure has led to a regime that is extremely resistant to elite-led reforms. This makes the regime ill-equipped to adapt and deal with popular pressures, and more prone to escalating crises, whether political or economic.

The regime seems set on a path that will only deepen the country’s crisis, leading to an eventual spillover of popular anger that it is not prepared to handle.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].