King Tut centenary: Where oh where are the Egyptians in Egyptology?

One century ago, the tomb of Tutankhamun was found. It was, and still is, the “blingiest” archaeological find of all time - and so, in 1922, Tut-mania was born.

A few months later, an English lord and an American millionaire associated with the tomb died; the hysteria was palpable. Tut’s “curse” hooked the media, and their list of “victims” kept growing. Even today, memes have circulated that jokingly beg Egyptologists not to enter newly discovered tombs because, well, perhaps the world has been through enough of late?

The curse of Tutankhamun clearly only affected posh white guys. I'm an Arab woman. I guess some of us are born lucky

For the centenary, I was asked to present an international two-part TV series. We wanted to look into the origins of the curse story (we suspected that media rivalry was a major factor) and delve into possible microbiological explanations. My sister was nervous; friends raised eyebrows (“was I scared?”); but almost immediately, I realised something they hadn’t.

I quickly explained to the production team that I, not they, should enter all tombs first. I told them not to call me brave, not to label me a hero. Within the first two minutes of research, I saw a pattern - the kind you can’t unsee. The curse of Tutankhamun clearly only affected posh white guys. I’m an Arab woman. I guess some of us are born lucky.

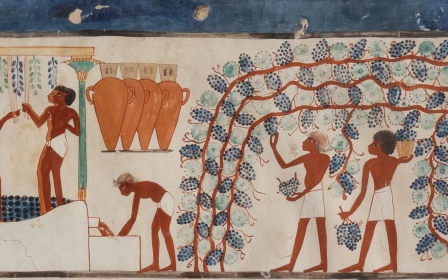

Tutankhamun was wearing a gold death mask and his tomb was filled to the rafters with treasure. As if that wasn’t enough, he was a boy king, the child of incest, married to his sister and the son of a religious revolutionary.

We archaeologists moan about the attention Tutankhamun gets, but let’s get real - our Neanderthal jaws or Roman walls can’t compete with that much gold and a telenovela backstory.

In the public’s imagination (and in Hollywood’s), Tutankhamun’s tomb is the archaeological benchmark. People want to know about him and are hungry for everything Egypt. Well, almost everything; that interest rarely extends to modern-day Egyptians. It’s as though a dead Egyptian is way more interesting than a living Egyptian.

Erasing Egyptians

Take “the curse”; the list of the dead was huge, some of the people whose deaths were attributed to the curse had never even been to the tomb, and yet, where oh where were the Egyptian names? Were there no Egyptians in Egypt that decade? Where had they all gone: Beirut? Damascus? Derbyshire?

None of us making the show believed in a curse, but are modern-day Egyptians so insignificant - is their erasure so extensive - that there is not even space for them in make-believe? Our incredible production team set to work, and found one Egyptian death attributed to the curse: Prince Ali Kamel Fahmy Bey. Just one guy, murdered by his French wife in the Savoy Hotel in London. He made it onto the list, while his wife, using a racist defence, never made it to a jail cell.

We suspected that conditions in the tomb, in particular a potentially toxic fungus called Aspergillus flavus, might have played a role in a few of the deaths. But a 100-year-old cold case isn’t the easiest thing to CSI. In the show, we pointed to a Polish tomb with a similar pattern of deaths - but here we were in Egypt, the land of tombs, so if they could be toxic, wouldn’t we find references to Egyptians dying in them over the years?

After much research, the team found a reference to a family around the time of Tutankhamun entering into an unopened tomb and dying.

I read this with absolute fascination, partly because the deaths were attributed to asphyxiation, jinn, etc - and partly because I realised that I urgently needed to rescind my first-person-in-the-tomb offer.

It took extensive research from our team, who held multiple degrees in archaeology and classics, to conclude something you would probably not have heard, read or watched - but yes, unfortunately, Arabs could die in tombs.

Racism and elitism

I kept replaying a question in my head: Egyptian workers on excavations outnumber archaeologists, so if tombs could be toxic, wouldn’t those on the front lines - the actual workers - be among the dead? What were their thoughts on microbes or the curse? We did something apparently revolutionary: we asked them. Who knew revolutions required so little work?

One foreman, Hassan, said he didn’t believe in curses or fear tombs, unless there was a mummy; he feared microbes. Egyptians, both workers and archaeologists, explained that upon discovering a mummy, they would vacate the tomb for a day or two and re-enter wearing masks and gloves.

Mahmoud Sayed, another foreman, explained that over the years, workers have developed safety protocols to deal with potential toxins.

The Tut toxic tomb theory is hard to prove, but Egyptian workers, famously not the most health-and-safety-conscious bunch, changing their protocols was as close to a smoking gun as I was going to get.

As the descendant of a Tut excavator, Sayed had one more insight, noting that when archaeologists realised what they had in Tutankhamun’s tomb, they pushed the workers aside. Foreign archaeologists were the first in, inadvertently reducing Egyptian exposure.

How is it that Egyptology and Egyptians are mutually exclusive? It doesn’t help that hieroglyphs and Arabic are unrelated, which means that Egyptologists get away with not learning Arabic and rarely speak it fluently. That’s quite unusual for those who study a region, and makes people removed from the descendants of the civilisation they study.

But let’s call it: this is also good old-fashioned colonialism, racism and elitism. From the beginning, the original archaeological team gave the Tut exclusive to the Times of London; the Egyptian media were shut out.

From the past to the future

Yet, this is far from a historical issue. The show Ancient Aliens, a History channel undertaking, plays with the idea that aliens built the pyramids. Apparently, for some, it is easier to believe that this remarkable ancient civilisation was built by beings from another planet than by the genius of brown earthlings.

We live in a world where we know how white people in London, Paris and New York viewed the discovery of Tutankhamun. Much has been written and filmed to that end. But have you ever heard about the contemporary Egyptian reaction? This gap seems particularly unfortunate and remarkable because 1922 was also the year that Egypt gained independence from Britain. Tut meant something for Egyptians - for their sense of national identity, pride and legitimacy.

Egyptians are all over Egyptology. They are obviously its past, but they are also its present and its future

Raphael Cormack, a specialist in 1920s Egypt, pointed me to a song by Mounira al-Mahdia in which she asserts: “Why do you think you are above us … Our father is Tutankhamen.”

I was forced to ask questions outside of the current paradigm, partly because I’m a British Arab. That doesn’t mean that only those with a connection to a place should be the ones to study or report on it; that would make us all poorer. Anyway, I’m Yemeni, not Egyptian. But the reverse is also true: it is time we start loudly asking where the Egyptians are in Egyptology.

If we never show Egyptians (both archaeologists and workers) on our TV shows; if we have no apparent interest in living, breathing Egyptians, then we are stuck in the past, but a past of our own construction - not one that really existed. A past where I’m sure Tutankhamun appears in our imagination as the product of skin-lightening cream.

There are, of course, many Egyptian Egyptologists, from Nora Shawki to Abdelrazek Elnaggar; their expertise runs the gamut. Egyptians are all over Egyptology. They are obviously its past, but they are also its present and its future.

Tutankhamun: Secrets of the Tomb, hosted by Ella al-Shamahi, is now available in the UK and Ireland on All 4 and is available now on National Geographic and Discovery Channel under the title "Tut's Toxic Tomb".

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].