Death of the peg: Why is Egypt's pound plunging?

Egypt’s pound is plummeting.

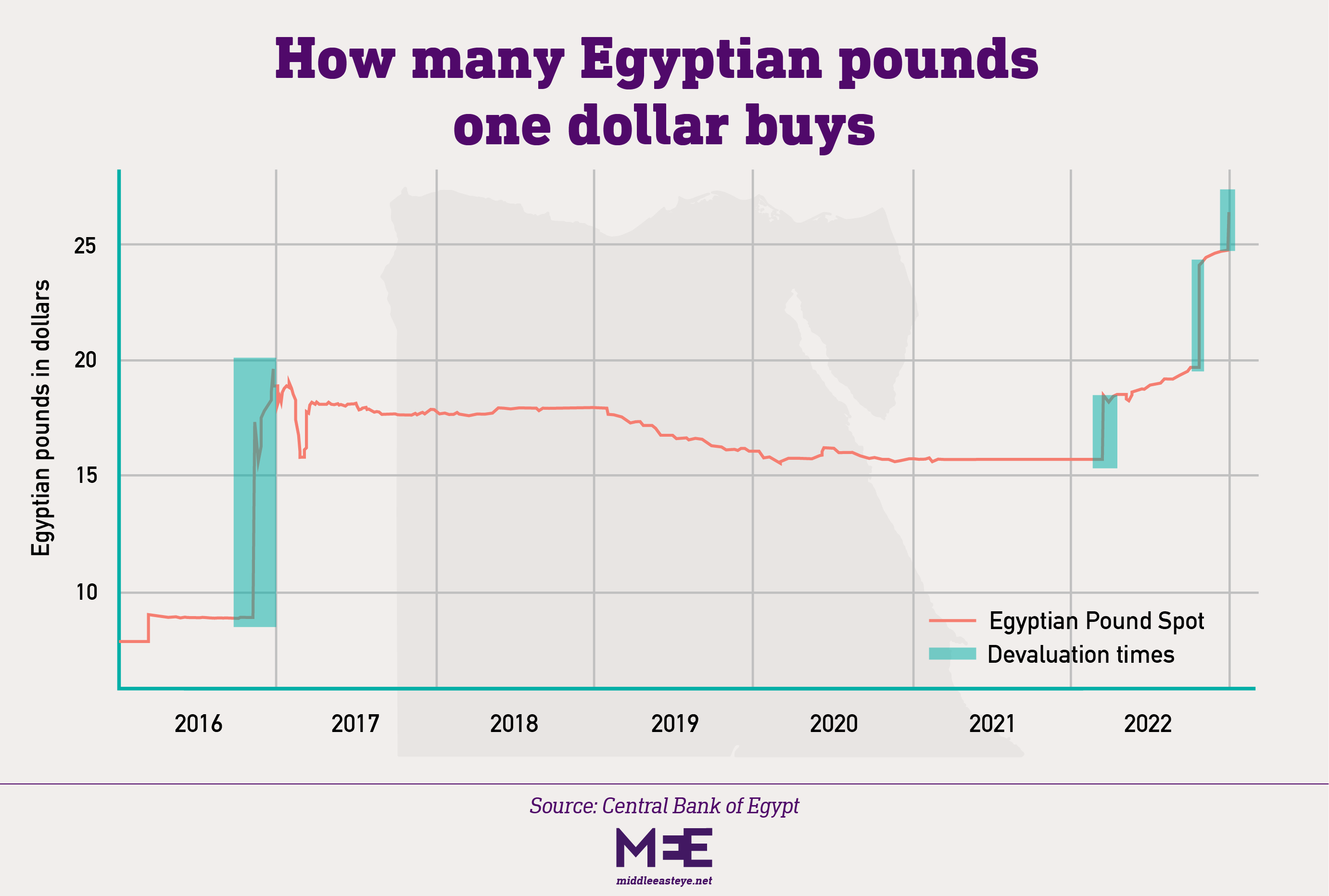

The pound plunged 40 percent against the dollar in 2022 - one of the worst performances of an emerging market currency last year - and this week, it kicked off 2023 by falling more than seven percent.

Middle East Eye spoke with economists and analysts to unpack why the currency of the Arab world’s most populous nation is falling - and why it's happening so abruptly.

The peg

The dramatic swings are the result of what Brad Setser, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and an expert on global trade and capital flows, calls Egypt’s attempts to move away from a “de facto dollar peg”.

Currencies like the US dollar, Euro, or British pound trade freely, meaning their value in relation to peers is determined by buyers and sellers agreeing to a price on the market. That’s why a chart tracking the Euro vs the US dollar zigzags up and down.

Not so for Egypt, where the government has tried to manage the pound’s rate of exchange. Between 2018 to 2021, a person could be confident that one US dollar would buy about 16 Egyptian pounds at the official rate of exchange.

“Egypt has traditionally linked its currency to the dollar,” Setser told Middle East Eye. There are lots of ways for governments to manage their rate of exchange, but the most straightforward is for central banks to use their foreign currency reserves.

“Egypt’s central bank will sell dollars into the market when they are in short supply or buy them when there are too many,” he said.

Currency pegs are common in the Middle East.

The Gulf states all peg their currencies to the dollar because much of their revenue comes from oil, which is priced in the greenback. Egypt also has foreign revenue sources - remittances from abroad, tourism profits and Suez Canal fees - but nowhere near the level of its wealthier neighbours.

Egypt’s government denies managing its currency, but analysts and economists say Cairo has supported the pound in an effort to keep prices stable and control inflation.

'The immediate impact is a drop in demand for imports'

- Charles Robertson, Renaissance Capital

“The peg means dollars are constantly flowing out of the country,” Charles Robertson, global chief economist at the frontier investment bank Renaissance Capital, told Middle East Eye.

“Egypt doesn’t have the foreign exchange reserves or foreign inflows to maintain a fixed exchange rate,” Setser added.

In an effort to conserve scarce dollars, Egypt's government had asked importers to provide letters of credit, creating a black market demand for dollars and a backlog of goods at ports. President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi said in December that the government would help banks secure foreign currency to clear the pileup.

Egypt has $45bn in debt payments due this year. But it’s struggling to find creditors. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, foreign investors pulled $22bn from its debt market. Rising interest rates in the West make Egypt a less desirable destination for foreign investors.

And its currency is just too high.

“Egypt has held its exchange rate at an artificially high level, at the same time they have huge debts coming due in dollars,” Patrick Curran, a senior economist at Tellimer Ltd, a firm that specialises in emerging-market research, told MEE.

“People we have as clients aren’t going to put their money into the country until the exchange rate is at a market clearing level,” Curran added. “Markets are still pricing in 20 percent depreciation over the next year and the currency is trading below the black market rate."

In December, Egypt turned to the IMF for its fourth loan from the lender in six years. As part of a $3bn deal, Cairo agreed to shift to a “flexible exchange rate regime", agreeing to let the pound's value be determined by market forces.

Since then there have been several abrupt devaluations in the pound.

“What we are seeing during the drops is the government taking their hands off the steering wheel, letting it (the pound) adjust in line with where supply and demand says it should be," Curran said.

As the pound decreases in value, imports become more expensive. In effect, it is a form of national belt-tightening. What Egypt must do, Robertson from Renaissance Capital says, is produce more and consume less, particularly from abroad.

“As the currency weakens, Egypt’s exports will become less expensive and more competitive, that’s a longer-term response,” he said. “The immediate impact is a drop in demand for imports.”

The pain is being borne by the Egyptian people, who are experiencing massive price hikes in everything from medicine to electronic appliances, as the pound drops in value.

The currency depreciation is also feeding into higher inflation, which Capital Economics, a London-based consultancy, expects to peak at 27 percent by the end of March. In November, Egypt’s inflation hit 18.7 percent.

Capital Economics says there are already signs that the depreciation is having an effect, with the country benefiting from increased competitiveness in exports. Gulf states, wary of a potential economic collapse, have also pledged billions of dollars to try and shore up the economy.

But Setser says a lot more pain is to come for ordinary Egyptians.

“The successful outcome is one where Egypt tightens its belt, gets additional help from its neighbours, and catches a break with food prices falling and tourism picking up.”

“The risk is that Egypt’s debts spiral out of control.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].