How Syria became Erdogan's Achilles heel

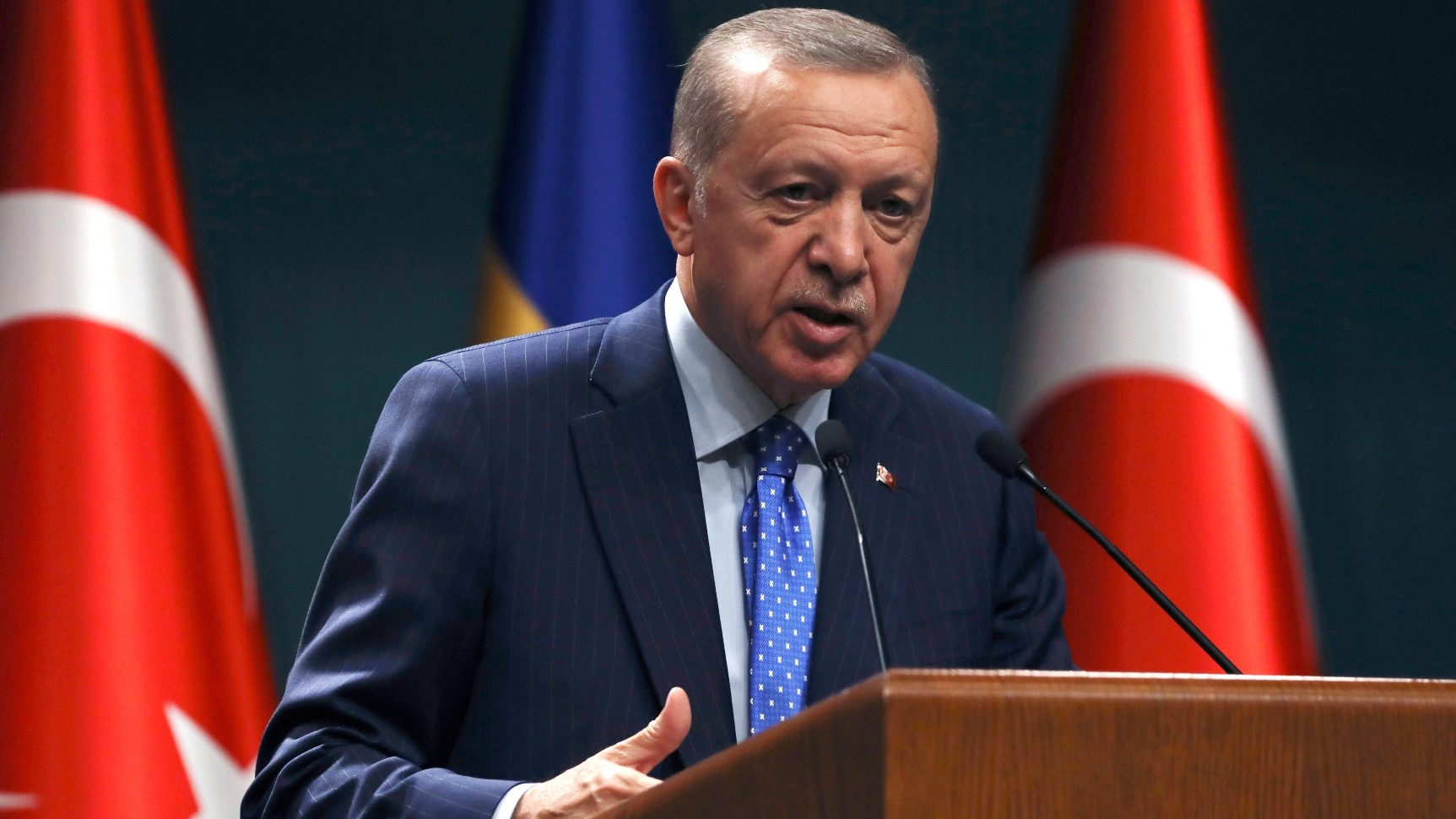

Much has been written recently about the Turkey-Syria rapprochement, meetings in Moscow, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's own statements on a potential meeting with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

While the word rapprochement might be overused, the real issue facing Turkey is a crisis of Erdogan's own creation. More than a decade ago, Erdogan called Assad his brother and thanked him for sorting out old border issues that had divided communities since the time of the foundation of the two republics.

Many Syrians are not keen on a rapprochement, given what they see as a historical invasion of Syrian land by the Turks

Two new books shed light on both Erdogan's war in Syria and the last days of the Ottoman Empire, which resulted in a fractured border, burdened with the same problems today as it was upon Turkey's founding. Erdogan's fortunes have fluctuated with the war in Syria, and the refugee crisis along the Turkey-Syria border is a rendering of what transpired a century ago - a problem that Erdogan himself once asserted that Assad had solved.

Gonul Tol's Erdogan's War offers a unique exploration of the Turkish president's rule, from his rise domestically to regionally, as a player upending decades of previous Turkish policy that had shied away from the Middle East and North Africa. Tol argues that the war in Syria and Erdogan's own ties with Damascus have shaped his domestic allies and foes.

Pivotal role

Though Tol is not the first to link the fates of Syria and Turkey over the last decade, she draws an interesting parallel: Erdogan used Damascus as his first Arab capital to rekindle Turkey's ties with the Arab world, before expanding to others, from Tripoli to Doha. Meanwhile, Assad abolished any camps and support in Syria, going back to his father's era, that aided groups opposing the Turkish state, including the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).

Assad also helped improve ties with the small but significant Assyrian and Orthodox communities in Mardin, Sanliurfa and Diyarbakir. With domestic threats contained, Erdogan took on the mantle of aiding reforms in the Arab world prior to the 2011 Arab Spring, and was viewed as a model for the region by most western countries and the Muslim world at large.

Syria under Assad played a pivotal role in helping Erdogan fight the PKK and forge an alliance with Turkish nationalists and the deep state, which had once doubted Erdogan's resolve.

Tol also examines the unravelling of Erdogan's political allies and the constant reshuffling of Turkish military generals. The breakdown of Turkey-Syria relations after the Syrian war began meant that there was now a two-pronged war, in addition to tensions with Russia, culminating with the 2015 downing of a Russian jet by Turkish forces and the killing of the Russian ambassador in Ankara, both linked directly with Erdogan's Syria policy.

Issues around Syrian refugees, demographic changes and economic woes have prompted Turkish opposition parties to push for reconciliation with Assad, contravening Erdogan's Syria policy. In addition, issues with Turkish Alevis, Kurds and the Christian community worsened as they fell afoul of Ankara's Syria policy. Armenia and Greece also revived old hostilities with Turkey, remembering their historical connections with Syria.

Stark parallels

The second book, Ryan Gingeras's The Last Days of the Ottoman Empire, draws stark parallels between those days and modern-day Syria, including issues with Armenians, Greeks, Arabs and Kurds - all themes that Tol discusses in relation to Erdogan's war in Syria.

When the Greeks were driven out of Ottoman lands, many found refuge in Syria. In the modern context, both the Greek and Armenian states clearly sided with Assad against Turkey. Communities in southern Turkey were not comfortable with Erdogan's war, as it upset the fragile balance that had held since peace with Syria was achieved in the mid-2000s.

Gingeras also talks about the sensitive issue of how Mustafa Kemal Ataturk wanted to "liberate" more areas under the French mandate, beyond just Hatay.

Indeed, the current war in Syria is viewed by many Syrians as yet another infringement on Syrian territory, echoing the process that unfolded decades earlier. Many Syrians are not keen on a rapprochement, given what they see as a historical invasion of Syrian land by the Turks.

It is thus important to remember that the Greek Orthodox and Armenian communities of Syria have allies in Athens and Yerevan, making this a regional issue for Turkey, just as it was in the last days of the Ottoman Empire. I have said before that the current situation is not about rapprochement, but rather about Erdogan needing Damascus. Tol and Gingeras bring both modern and historical relevance to how Syria became Turkey's Achilles heel.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].