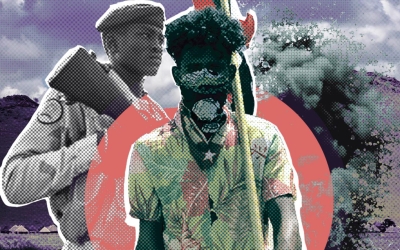

The Sudanese armed leader gaining power in the vital Red Sea region

In the Deim Madina neighbourhood near downtown Port Sudan, dozens of young men mill around an office full of weapons, drinking coffee and tea as they wait to get their IDs as militiamen.

A banner for the Beja Congress party hangs on the door and walls of the office, along with a slogan that reads “Armed struggle”.

Elsewhere in the building, young fighters are learning how to operate and disassemble light weapons, including pistols and guns.

Welcome to the operation of one of eastern Sudan’s most powerful men.

Dirar Ahmed Dirar, an armed leader with increasing influence in Sudan’s Red Sea region, has vowed to use weapons to liberate the Beja people, who are native to eastern Sudan, from “historical marginalisation” by governments in Khartoum.

Also known as “Shaiba Dirar”, the militiaman and his men openly carry weapons in the strategically vital Red Sea city of Port Sudan, the country’s major seaport, which handles about 90 percent of Sudan’s foreign trade.

Competition for resources and control of the ports is widespread and fierce in the Red Sea region, but the Sudanese authorities - including military intelligence, the security services and the police - are not stopping Dirar and his fighters from bearing arms in public.

This has led to questions about whether Dirar is being supported by the military government in Khartoum, and to a widespread belief that shipping and trade in the east of Sudan are now at the mercy of the armed leader.

Dirar welcomed Middle East Eye into his office for an exclusive interview and explained the exercises his men were performing in the yard.

“These are the light exercises, but we do shooting training in the mountains far from the city and you are welcome to join us, we have nothing to hide,” he said in the yard.

When MEE asked about the offer of going to the mountains to see this training, Dirar apologised and said he had to go to Khartoum for a meeting, but refused to reveal who he was meeting.

Inside the militia leader’s office were dozens of pistols, guns and manuals for bombs manufactured in Sudan, Israel, Russia and China. Among the weapons was teargas made by the Military Industry Corporation (MIC), Sudan’s state-run defence corporation.

'We don’t get support from anybody, but we won’t give up our secrecy - at least not now - because we are in the front line at the moment'

- Dirar Ahmed Dirar, armed leader

A small banner reading “Lieutenant General Dirar Ahmed Dirar” could be seen.

After a short conversation, Dirar told MEE to take photos of him carrying a gun, as well as of the weapons stored in the corner of his office.

He talked up his and the Beja Congress’s growing influence and the range of their activities.

“We have our military camps for our forces at the border between Sudan and Eritrea, in the areas of Talkook and other places around, and we have our military training areas in the mountains, far from the eyes of the authorities,” he said.

“We have thousands of forces from the former army of the Beja Congress party and others who joined us for different reasons - particularly because of feelings of unfairness, of the discrimination and inequality against the people of eastern Sudan.”

The armed leader did not disclose his sources of financing, logistics or supplies, including weapons.

“As the SPLA hero John Garang said, we always depend on our enemy to grab the weapons, uniform and supplies we need for our army,” Dirar said, laughing heartily.

“We don’t get support from anybody, but we won’t give up our secrecy - at least not now - because we are in the front line at the moment,” he said.

Eastern promises

There has been a prolonged struggle for power in Sudan’s resource-rich east, which is home to diamond and gold mines, as well as the vital Port Sudan.

Just as in Darfur and other parts of Sudan, local groups have long argued and fought for a restructuring of power that alleviates poverty in their region and transfers power from the capital, Khartoum.

Dirar is part of the Amarar tribe, which is part of the Beja ethnic group that considers itself the rightful possessor of the lands of eastern Sudan.

'He has given us salaries, weapons and protection, so why not, seeing as we don’t get anything from the government'

- Armed fighter in Port Sudan

In 2006, eastern Sudanese rebels, who had been allied to former southern rebels and those from Darfur, agreed a peace deal with the government of then-president Omar al-Bashir, who ruled Sudan from 1989 before finally being removed as part of a democratic uprising in 2019.

The deal, which ended a decade of low-level revolt in the east and ushered in a power-sharing agreement, was mediated in neighbouring Eritrea and became known as the Asmara peace agreement.

Now aged 60, Dirar was part of the Beja Congress delegation that signed the agreement with Bashir’s government. He then participated in the government of the Red Sea state.

The Asmara deal included a disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration programme, but hundreds of combatants were not subject to it and they have joined Dirar’s forces.

Three sources in Port Sudan, who requested anonymity for security reasons, revealed that they have military IDs from Dirar’s small army. They gave no further information about how these were obtained.

“I’m currently a colonel in Shaiba’s army. We believe that we have to do this as Beja people… you see now, after the signing of the Juba peace agreement, every group of people is defending their region, and you see the government has given a lot of privileges to the people of Darfur because they carried weapons,” one of the sources told MEE.

Another source told MEE hundreds of unemployed young people had been handed military IDs.

“He [Dirar] has given us salaries, weapons and protection, so why not, seeing as we don’t get anything from the government.”

'Freedom fighter'

“I’m not a militia leader or someone who wants to create troubles. I don’t have problems with anyone,” Dirar told MEE.

“But I’m a freedom fighter that wants to liberate eastern Sudan from this inequality. We want to stop this historical marginalisation and create equal citizenship.”

Shaiba warned that he wouldn’t just close the ports to exports and imports but might even close all three states of eastern Sudan: Red Sea, Kassala and Gedaref.

“We can’t stay and see our resources being looted by the centre of the country for ever, we will stop this one day,” he said.

Dirar is part of a group of tribal leaders who closed Port Sudan in 2021 to pave the way for the military coup. But he closed the port once again last December, as he rejected the civilian-military deal brokered by international sponsors.

Most of eastern Sudan’s tribal leaders have also rejected the track laid out by the 2020 Juba agreement signed by the Sudanese government and the country’s five main rebel groups, and have closed ports several times as a way of trying to get the Khartoum government to freeze the agreement.

The crisis in eastern Sudan is also one of the issues yet to be addressed by the framework agreement signed recently by military and civilian representatives in their attempt to beat a pathway back to something that resembles democratic government.

Tribal leaders, activists and military experts have doubts about whether Dirar is getting support from those aligned to the old Islamist regime of Bashir or from parts of the military that rejected the deal signed last December between the army and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) civilian-political coalition.

Mohammed Osman Sharif, deputy leader of the Amarar tribe, told MEE he thought the Sudanese “deep state” was behind the destabilisation of eastern Sudan, which had paved the way for wider instability in Sudan.

“They are aiming at obstructing the democratic path in general through eastern Sudan, as they did in October 2021,” Amir Hassan, a resistance committee member from Port Sudan, told MEE.

Military experts also warned that the use of military tactics, such as the arming of tribal leaders, would have serious consequences.

“This will lead to the spread of weapons, an uncontrollable security situation and chaos in this strategic area. These sabotage tactics were supposed to be stopped immediately by the intelligence services,” one expert, who asked to remain anonymous, told MEE.

“Political engagement, not arms, is the only solution for the problems of Sudan, particularly eastern Sudan,” the expert added.

Dirar's response is that he was not aiming to cause chaos, but that the only way to counter the weapons used by the central government over the years was to use weapons yourself.

Right now, he told MEE, he will keep fighting for eastern Sudan.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].