Why Israel's new and leaderless protest movement is different

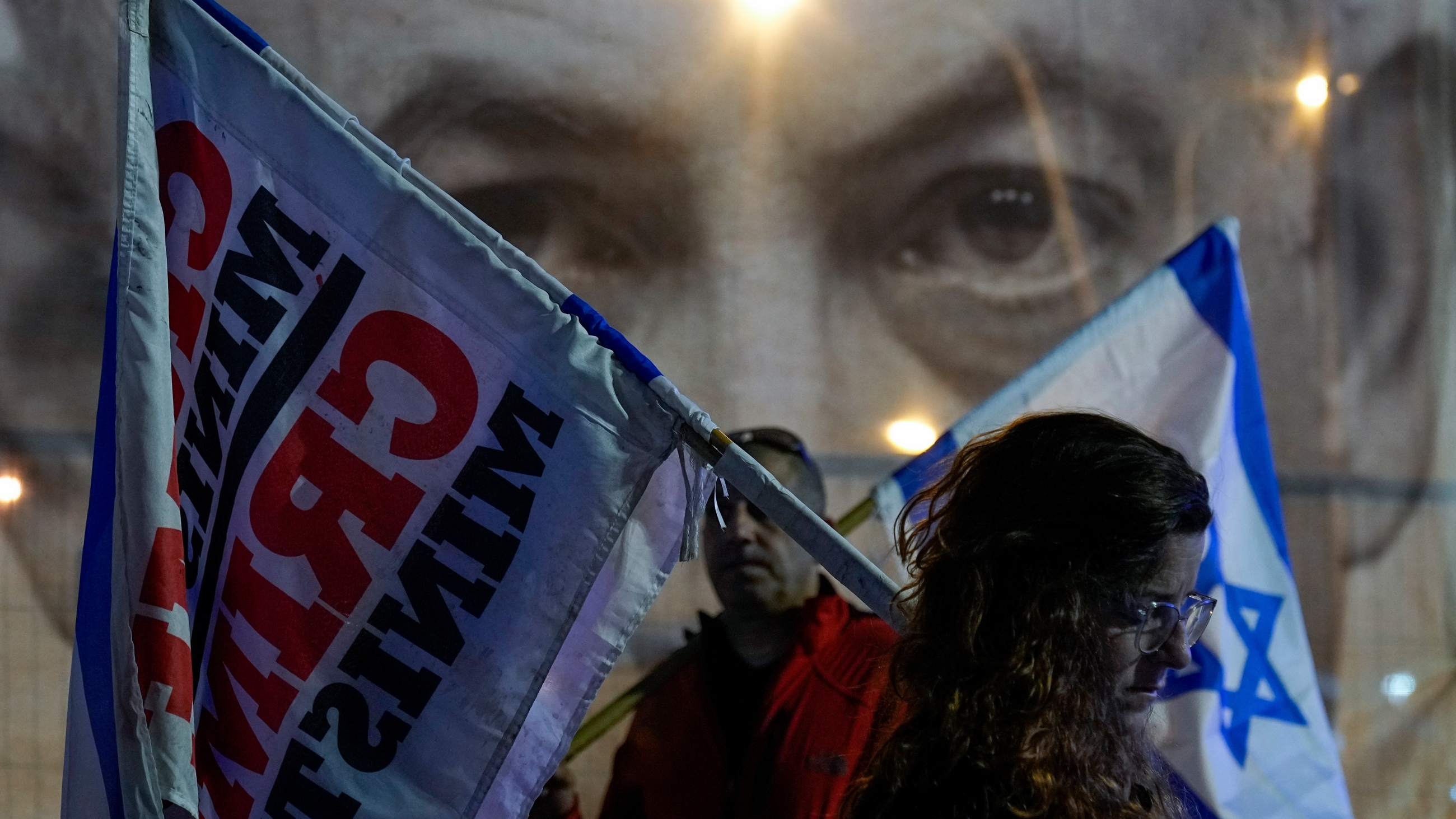

On Saturday night, for the fourth week in a row, thousands of Israelis took to the streets to protest against the upcoming "regime change", known officially as “judicial reform”.

That a mass demonstration took place hours after two attacks in which Israelis were killed marks a profound shift in the Israeli ethos.

For decades, a major tragedy like the shooting on Friday night in which seven people were killed outside a building used as a synagogue, in the settlement of Neve Yaakov, would put on hold any protest.

Those protesting sense that something much bigger is going on. They once read about it happening in Poland and Hungary, and in the same order

Faced with a choice between social rift or solidarity in times of war or grief, Israelis used to opt for solidarity.

Mandatory military service and long years of reserve service play a crucial role in shaping society, and solidarity in times of danger or sorrow was one of its most remarkable manifestations.

Years of cynical, self-serving leadership has eroded this sentiment. And now that the government is engaged in a brutal assault on half its people in the form of judicial reforms, the rules of the game have changed.

The mass protest began just days after Likud’s newly elected justice minister, Yariv Levin, presented his plan, which almost all the prosecutors and state attorneys who have served in Israel in the past half century have warned will “destroy” judicial independence if passed by parliament.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, bound by conflict of interest rules from getting involved with legislative matters that might affect his ongoing corruption trial, has openly promoted the plan.

The mass protest that kicked off less than a month ago with a few thousand people on the streets of Tel Aviv had reached an estimated 100,000 protesters by last Saturday night.

Most of them may not really understand the terminology and the subtleties of the law. What they do understand is that the newly elected government is on a mission to change their country. Just because they want to. Just because they can.

A different kind of protest

Over its 75 years of existence, Israel has known many protests, political and social. The political ones were divided between left and right; the social ones were defined by socio-economic status. Only a few have been even somewhat effective.

The wave of protests we are seeing now are different. Previous ones came as an after-the-fact response to a political or social development – a war without popular consent, ongoing ethnic discrimination, soaring prices, the Sabra and Shatila massacre of 1982, the Oslo accords, and so on.

The present protest wave is a preventative one that seeks to stop not only the upcoming judicial overhaul but also to hold onto what is left of the country and guard against further moves to erode what is left of its democracy.

Weekly mass rallies are now met with government threats to shut down the public broadcaster and block the publication of “sensitive information”.

Israelis hear Netanyahu publicly wave away warnings from the governor of the Bank of Israel, who has said that the planned judicial reforms would hurt the economy.

They listen to a coalition Knesset member calling for the imprisonment of both former Prime Minister Yair Lapid and former Defence Minister Benny Gantz, who are now both in opposition and are accused of “betraying” the ruling government.

The anti-democratic slide

Those protesting sense that something much bigger is going on. They once read about it happening in Poland and Hungary, and in the same order: leaders sidelining the judicial system, the media, opposition, restricting the civil rights of minorities, glorifying white or Polish or Catholic or Jewish supremacy.

They have even head about a similar process in Germany in the 1930s, though they will have been warned not to make that comparison.

They are angry and terrified, this time not only as individuals, but as sectors of society worried about the implications for their professions and their communities.

In an open letter, hundreds of economists, many of whom had previously been appointed by Netanyahu to leading positions, warned that the judicial overhaul could cripple the economy.

The majority of protesters still insist on divorcing the future of democracy from the basic question of 57 years of occupation

The prime minister rebuffed their claims. Just days later and major startups were moving their money and business out of Israel. Hundreds of tech workers - certainly not radical leftists - have held strikes, blocking roads in Tel Aviv.

There are many more examples of this kind of dissent, from doctors warning against the implications of judicial reform on the healthcare system to the education ministry issuing a warning to all teachers. Judges have resigned, retired pilots have rallied, students and architects have organised.

Netanyahu has been quick to refer to all these myriad responses as being “part of the leftist bloc”. Others call them “non-Zionist”, a term used to undermine their legitimacy.

While these sectors are identified, the forces behind the mass rallies are less obvious. Unlike in previous demonstrations there is no single organising organ.

Some of the movements previously instrumental in the long “Balfour protest” in front of the prime minister’s official Jerusalem residence - which helped remove Netanyahu from office in 2021 - are engaged in the new protest.

So too is the veteran grassroots organisation Movement for Quality Government. But these rallies have no active leadership and no acting politicians are invited to speak.

Parliamentary opposition is hardly visible and plays no role - other than in the presence of individuals - in the protest.

Palestinian involvement

Avigdor Lieberman, head of the Yisrael Beiteinu party, now in opposition, boycotts the rallies. He is against all demonstrations that feature Arabs and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) flags.

In fact, Lieberman has little to worry about. Palestinian citizens of Israel hardly take part in the mass rallies.

They have many reasons to be there, since what this racist government is planning - including a pending bill to ease disqualification of Arabs from the Knesset - will have a particular impact on their lives.

But they have more reasons to stay away. Israeli democracy has always worked for Jews mainly; thus a common struggle for its preservation cannot now be taken for granted.

Neither can they accept the tacit ban on flying Palestinian flags imposed by protesters terrified by their identification with “the enemy”. The search for a Palestinian flag amid thousands of Israeli flags has become a sort of sport for government supporters looking to delegitimize the protests.

'In the face of this darkness, only widespread civil disobedience will work'

- Yair Golan, retired general

Then there is the issue of occupation. The majority of protesters still insist on divorcing the future of democracy from the basic question of 57 years of occupation.

Many really don’t see the link. Others divorce the issue for tactical reasons, fearing that they could antagonise potential partners-in-arms.

The solution has been a territorial separation. One big rally takes place every Saturday evening on Habima Square in central Tel Aviv: Israeli flags only, consensual speakers only.

Another begins on Kaplan Street, near the government compound in Tel Aviv. This is where the radical, anti-occupation bloc finds its place.

Under the slogan “There is no democracy with occupation”, movements like Combatants for Peace, Machsom Watch, Peace Now and A Land for All mingle in the huge crowd and connect the current situation to the ongoing occupation.

The self-evident truth about occupation is still seen as a defiant statement. Even when it is accepted, it is not yet internalised.

In the northern city of Haifa, where both Jews and Palestinians live, the Hadash Arab party holds its own small demonstration with an emphasis on occupation, with almost no Jewish partners.

It could - and maybe should - be different now. Addressing a mass Tel Aviv rally a week ago, author David Grossman said that many Israelis now feel “exiled in their country”.

It is certainly not the same, and probably even unfair to compare, but this is the closest Israeli Jews have come to the sense of alienation and rejection that has been part of the lives of Palestinian citizens of Israel for decades.

This sentiment, newly acquired by many Israeli Jews, could bring the two societies together. It is not really happening - yet.

In 2019, at an opposition protest against Netanyahu’s government, then parliamentarian Moshe Ya'alon openly criticised the fact that Palestinian-Israeli politician Ayman Odeh was invited to deliver a speech, suggesting that potential Likud participants would leave.

Last Saturday, Ya'alon, a retired general who served as the Israeli army’s chief of staff, was the key speaker at the mass demonstration. This is just a small example of the complexity of Israeli politics and society in times when cohesion is much needed.

Heavyweight presence

Ya'alon is not alone. The involvement of retired military personnel in the protests stands out.

Ehud Barak, the former prime minister and one of the most decorated soldiers in the history of the Israeli army, is the most outspoken senior figure at the protests. He is also, according to some sources, one of the protest movement’s financiers.

Barak warned seven years ago that Israel had been “infected by the seeds of fascism”. Today, he says openly that the government “bears the signs of fascism” and calls for civil disobedience.

So has retired general Yair Golan, a former Meretz Knesset member.

Following the two deadly attacks in East Jerusalem, Golan tweeted: “I’ve been saying for months that Bibi will drag us all to some crisis - be it security, economy, whatever… the principle is simple - to prepare a platform for emergency legislation that will lead to cancellation of his trial. It’s so obvious… in the face of this darkness, only widespread civil disobedience will work."

In Israel in 2023, high military rank still confers on the bearer the privilege to say things many only dare to think.

Civil disobedience is the next step. Everybody talks about it, but nobody really knows what it means. There is no tradition of civil disobedience in Israel and so it is often confused with civil war, the literal Hebrew translation of which is “brothers war”.

In the meantime, the steps considered are mainly widespread strikes. Ya'alon calls for disobedience against the new laws, if they pass. The radical bloc calls for refusal to serve in the army.

What is clear is that there is now no time to waste. In fact, it is a race against time. Itamar Ben-Gvir, the far-right national security minister, has warned for weeks that another round of riots is to be expected.

After the two Jerusalem attacks, an escalation in violence is most likely. Nothing will serve this government better than that. They seem to be looking for it to kill the protests.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].