Abdel Fattah al-Burhan: Israel's man in Sudan

Israel’s foreign minister arrived in Khartoum earlier this month without much fanfare, but with a proud acknowledgement from Sudanese authorities. Eli Cohen first visited the city in January 2021 when he was serving as Israel’s intelligence minister. This time around, his delegation included Ronen Levy, the freshly appointed director general of the foreign ministry who was reportedly a critical behind-the-scenes operator for the Abraham Accords.

Sudan signed the Abraham Accords in January 2021, a step viewed as a condition for US munificence in removing Sudan’s name from its list of state sponsors of terrorism, and paving a loans-ridden route for Sudan’s reintegration into the global financial system after decades of exclusion.

The only credible dissenters in Khartoum are the young women and men who have been demonstrating on the capital's streets

Sudan had reached out to Israel a year earlier, when General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan - who came to power after countrywide popular demonstrations preceded a 2019 palace coup against former leader Omar al-Bashir - held a meeting in Uganda’s Entebbe with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in February 2020.

Burhan later switched partners in another coup in October 2021, which saw Sudan’s government collapse at the hands of the country’s military formations.

Of particular relevance is the challenging relationship between the two main armed formations in Sudan: the regular army under Burhan’s command, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. Burhan and Dagalo have to cooperate in the short term, while each of their long-term prospects is predicated on the subordination of the other.

Dagalo made himself a regional asset through his contribution to the Saudi-Emirati war effort in Yemen. The RSF is also fighting rebels in the Central African Republic in return for mineral rights, and it recently redeployed along the Sudan-Chad border as part of a scramble for gold alongside the Russian military firm Wagner.

Dagalo has publicly said Sudan should move ahead with a Bashir-era deal to install a Russian naval base on the Red Sea, but he does not have the means to see that proposal through, despite his considerable influence in western Sudan and beyond. Sovereignty over the coastline remains a prerogative of the military leadership.

Strengthening military ties

Burhan, on the other hand, is investing in the technical capabilities of the army by strengthening relations with traditional allies, primarily Egypt.

The two militaries carry out regular war games, and they formalised their cooperation through an agreement signed in Khartoum in March 2021. What the army needs are arms to help it monitor and secure the western hinterlands, but Sudan has been under a UN arms embargo since 2005 in relation to the war in Darfur. Sudanese diplomats have doggedly sought to end the embargo, citing the success of the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement.

The UN in Sudan operates politically through its Integrated Transition Assistance Mission (UNITAMS), which together with regional organisations has been playing the role of mediator to restore the status quo ante prior to Burhan’s October 2021 coup. These efforts recently crystallised into a framework agreement signed last year between the military bloc and opposition forces.

The proposed settlement includes a commitment by the military to hand over executive power to a civilian government. Military reforms and the eventual integration of the RSF would be carried out by the army leadership.

In a way, the agreement keeps the door open for the military to interfere in civilian affairs, but not vice versa. The military leadership would ultimately maintain power over whether, and how, to change the security apparatus.

Some rebel factions remain opposed to the framework agreement, and Burhan and his officers can manoeuvre among them. Burhan’s Egyptian allies recently organised a round of talks for opponents of the framework agreement in Cairo, after Egypt’s security boss, Abbas Kamel, visited Khartoum, likely with an eye to granting the counter-bloc greater visibility and political currency.

Dagalo, the deputy head of state, has also attempted mediation between the two blocs, probably in an effort to derail the pro-Burhan Egyptian machinations. Both seem to have failed.

Border zone

In Khartoum, Kamel reportedly asked Burhan to find ways to address Wagner’s use of Sudan as a base for operations in neighbouring countries - an objective that sets Burhan and his Egyptian allies directly at odds with Dagalo and his RSF.

Last month, Burhan visited Ndjamena, the capital of Chad, probably to discuss the security situation on the increasingly militarised Chad-Sudan-CAR border zone. Dagalo followed separately on his heels, probably to counteract whatever his boss was devising.

Cohen arrived in Khartoum at this moment, as competition between Burhan and Dagalo has been playing out in the context of domestic alliances and counter-alliances, and a regional tug-of-war along Sudan’s western border.

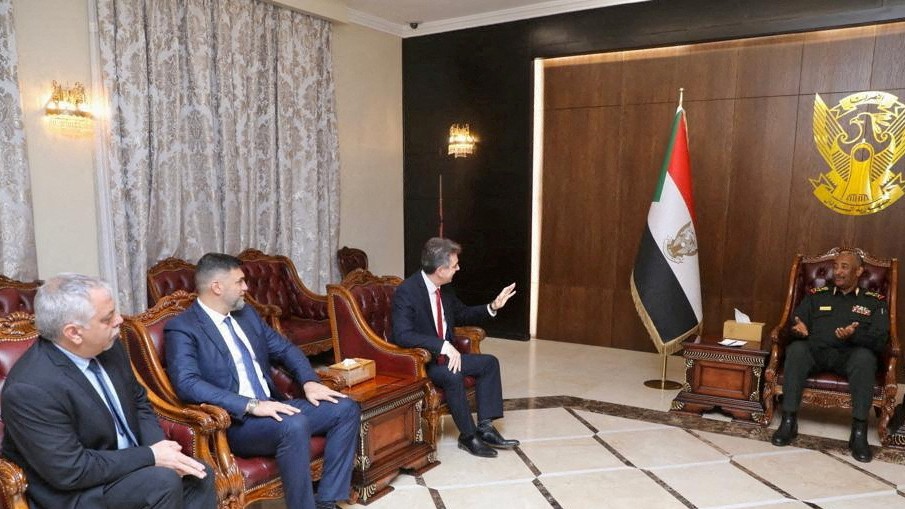

Ahead of Cohen’s visit, Sudan’s spy chief, Ahmed Ibrahim Mufaddal, concluded a brief trip to Washington for an audience with the US intelligence establishment. In Khartoum, Cohen was received by Burhan and other key defence officials - but remarkably, Dagalo said he was kept in the dark about the Israeli visit.

The declared outcome of Cohen’s visit was a pledge by the two sides to formalise their relations through a bilateral treaty that would include military, security and economic cooperation - an agreement to be signed as soon as a civilian government is in place.

Judging by the current circumstances, however, it would have to be Burhan’s civilian government.

Burhan has shown he is an asset to the formidable security regime around the Washington-Tel Aviv-Cairo axis. The only credible dissenters in Khartoum are the young women and men who have been demonstrating on the capital’s streets against this architecture of oppression.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].