Homeland Security: Two decades of terrorising people of colour

In a Twitter thread commemorating its 20th anniversary on 1 March, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said: "DHS was created in the wake of the 9/11 attacks to safeguard the US against terrorism...Today, homeland security is national security - and our mission to ensure a safer, more secure, and more resilient America remains the same."

While DHS has continued to maintain the facade that it exists to protect Americans - claiming in its bulletins to thwart threats against "racial and religious minorities" - it has spent the last two decades subjecting these very communities to its violent abuse.

Bush was preemptively legitimising all the violence that would be committed in the name of protecting US national security and his construct of an American 'homeland'

DHS was established in 2003 with a budget of $9.1bn. The department incorporated 22 agencies including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) - previously the Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Customs and Border Patrol, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the Secret Service.

While the government justified the need for DHS as a matter of efficiency and collaboration, it was not only a political tactic but also a rhetorical one to position three agencies that address immigration and migration under an institution whose mandate is to "protect" the American people - read: white Americans.

In 2011, DHS implemented the National Terrorism Advisory System as a replacement for the previous system of colour codes used to indicate threat levels.

Despite highlighting a threat to racial and religious minorities, absent from these alerts and bulletins is an acknowledgement of the consistent and destructive threat that the agency itself poses to these very communities. Regardless of the system and their theoretical goals of preventing threats to the US, both are telling about who the government is actually seeking to protect and from whom.

A homeland for whom?

The trajectory of the war on terror over the last two decades has more than abundantly revealed the government's aims and which citizens it values over others.

It is nevertheless important to examine the foundational narratives on which this dividing line - those in need of protection and those who constitute a threat - was built.

Nine days after 9/11, on 20 September 2001, then-US President George W Bush delivered one of the most consequential and pivotal speeches of his tenure.

Delivered to a joint session of Congress, it was in this speech that Bush would use the term "war on terror" for the first time while outlining his administration's vision for a massive military response that would far surpass the magnitude of the 11 September attacks.

It was also in this setting that Bush first referred to the "homeland". Directly preceding his statement announcing the creation of a Cabinet-level position in the Office of Homeland Security, he stated:

"Our nation has been put on notice: We're not immune from attack. We will take defensive measures against terrorism to protect Americans. Today, dozens of federal departments and agencies, as well as state and local governments, have responsibilities affecting homeland security. These efforts must be coordinated at the highest level."

Throughout the speech, Bush also constructed core narratives - ones that endure today - about why the US was attacked (freedom and democracy) and who carried them out (al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and others amorphously described as "the terrorists").

But, perhaps most significantly, Bush cemented the US's position as a victim targeted for inexplicable reasons. By laying claim to a unique status of victimhood, he preemptively legitimised all the violence that would be committed in the name of protecting US national security and his construct of an American "homeland".

The rhetorical theatrics of the term "homeland" would be weaponised once again about 14 months later when Bush announced that he was signing the Homeland Security Act of 2002. To this end, he asserted:

"We're fighting a new kind of war against determined enemies…With the Homeland Security Act, we're doing everything we can to protect America. We're showing the resolve of this great nation to defend our freedom, our security and our way of life. It's now my privilege to sign the Homeland Security Act of 2002."

Bush never explicitly defined what he meant by homeland. But from the cascading "war on terror" developments, it was clear that he was using the term as a warning to those it would deem as a threat - to say nothing of the obvious irony of claiming a homeland on a settler-colonial state.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary, for example, defines homeland as "a state or area set aside to be a state for a people of a particular national, cultural, or racial origin". In other words, homeland ties a particular identity together - and in the US, that has hardly meant Americans across the board. For whom then is protection reserved?

In their 2008 article, "Another Brick in the Wall? Neo-'Refoulement' and the Externalisation of Asylum by Australia and Europe", authors Jennifer Hyndman and Alison Mountz write that "the nationalistic production of home requires a constitutive outside, something against which home is defined".

In the context of the war on terror, the government intentionally used "homeland" to construct an identity of who belongs in the US and who doesn't, while also constructing which communities deserve protection versus those who constitute a threat to those deserving of protection.

A collective threat

Immigration and border regulation, as Nancy Hiemstra, a political geographer, notes, are fundamental to homeland security - security that is constructed as essential to protecting a white American nation.

With the Homeland Security Act in place and the full institutionalisation of the term homeland, nativism, racism, anti-blackness, xenophobia, and Islamophobia would come to constitute the war’s narrative infrastructure, and the laws and policies that have been and continue to be legitimised and implemented on this basis.

The government intentionally used the term 'homeland' to construct an identity of who belongs in the US and who doesn't

However, the Bush administration hardly waited for the Department of Homeland Security to be established before making it clear who the threat was. Wasting no time, in the weeks immediately after 9/11, many Arab and South Asian men started disappearing - many deported - and others detained, then deported.

While those targeted were innocent of any terrorist activity - singled out because they illegally entered the United States or overstayed their visas - it served the purpose of conflating immigration violations with criminality - and more to the point, a threat to homeland security.

A year later, in September 2002, the Bush administration implemented the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS) targeting male non-citizens from 25 countries - of which 24 were Muslim majority.

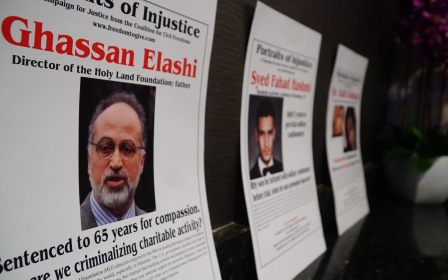

Forced to regularly check in with the government to provide residence and employment documentation, NSEERS resulted in 90,000 Muslims being registered. Though the programme was deemed unsuccessful because it resulted in no terrorism convictions, it allowed the US government to cement the entrenchment of Muslims and Arabs as a threat in the earliest days of the war on terror, as one of the central populations that threatened homeland security.

Since its inception, DHS "protected the homeland" by inflicting state violence on Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC), which includes, but is not limited to, the targeting of Black Lives Matter activists, the creation of the Countering Violent Extremism programme to surveil Muslims and other BIPOC communities, tearing families apart and putting them in cages, and executing foreign nationals across the border.

The commitment to targeting non-white populations based on the belief that they constituted the sole threat to the United States was made clearer by the fact it took the DHS 16 years to include white supremacist violent extremism in their strategic framework.

However, even when white supremacist extremism was included, they were compared to Islamic State to construct violence by groups identified as Muslim as the gold standard, while simultaneously preserving the idea of a certain character of whiteness that precludes any inherent propensity to violence or evil. In one example, a bulletin states: "Similar to how ISIS inspired and connected with potential radical Islamist terrorists, white supremacist violent extremists connect with like-minded individuals online."

In other words, even white people are legitimately a threat to homeland security, it’s only because of the precedent that non-white groups have set before them.

Resistance to actually tackling white supremacist extremism has continued while at the same time, the US government, regardless of administration, has continued to double down on non-whites as threats whether through the Muslim ban, or now the Covid-linked mass deportations under Title 42. This is no surprise, especially if we understand in certain terms what the purpose of counterterrorism is and has always been.

'American values'

In a more general sense, Professor Beatrice de Graaf, chair of the Utrecht University History of International Relations Section, defines counterterrorism as "a way of communicating to the audience what society should look like, what constitutes a collective threat, what actions are considered legal, and what is defined as alien and hostile".

It is these narratives that have continued to underwrite and justify state violence against Muslim and other BIPOC communities while simultaneously protecting white perpetrators of extremist violence.

It is these narratives that have continued to underwrite and justify state violence against Muslim and other BIPOC communities

Last Wednesday, Biden gave a speech at the Department of Homeland Security to commemorate its 20 years in operation, saying in part: "When I think of this department, I think of it in that way - standing up for American values."

The only American value that the DHS has consistently stood up for, however, is white supremacy. White supremacy is the raison d'etre for why this institution exists in the first place - never mind its violence over the last 20 years.

That’s why after 20 years, we must dismantle and abolish DHS. This means we have to consistently and collectively subvert and disrupt the problematic and demonising narratives of communities it has preyed on to justify its existence. Until we do, “homeland” will only serve as a weaponised proxy for white supremacy and the violence justified on this basis.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].