Iraq's 'authoritarian' alcohol ban a boost to black market and blow to minorities

In the 1970s, when certain foreign journalists were allowed access to officials of the Iraqi state, then Vice President Saddam Hussein would regularly provide them with a tray of glasses filled with what he called his country's "national drink", Johnny Walker Black Label.

Saddam was such a fan of the whisky that numerous pictures of the Iraqi ruler show him enjoying a glass of the beverage, often with a rifle in his other hand.

Reports allege that towards the end of his rule, he had been using international aid programmes to import thousands of bottles of whisky a week for himself and his inner circle.

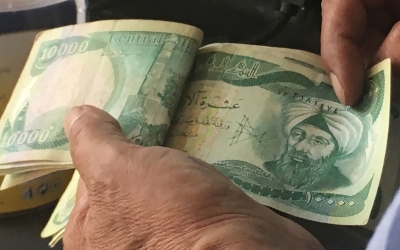

Times have changed, however. Last month, the Iraqi government published long-proposed legislation banning the import of alcoholic beverages into the country, no doubt including Saddam's beloved Johnny Walker Black Label.

'It is a violation of constitutional principles and rights and liberties, which are granted in the constitution, so I think the federal court should reject it'

- Ali al-Bayati, former rights chief

According to the new legislation, the sale or production of alcohol in Iraq is now illegal, while the General Customs Authority in a statement said it had "given orders to all customs centres to ban the entry of all types of alcoholic drinks".

The legislation, originally passed in 2016 but only becoming law after its publication in the official gazette on 20 February, is unlikely to affect the autonomous Kurdistan region that controls its own border crossings.

But the move is a blow to those who enjoy drinking alcohol, use it in their religious ceremonies, or produce and sell the beverages.

Even non-drinking Iraqis have said the restriction is a violation of civil liberties and a move to distract from the failings of the political class.

It is also seen as part of a creeping authoritarian trend in Iraq, coming on the heels of another new law criminalising the publication of material that "violates public integrity or decency" that has been used to crack down on social media influencers, comedians, and musicians.

Ali al-Bayati, the former head of Iraq's High Commission for Human Rights (IHCHR), agreed that the legislation was unconstitutional and another sign of an "authoritarian" creep in the country.

Bayati himself fled the country last year after being subjected to a legal complaint, purportedly stemming from comments made on a TV channel about the torture of detainees by an anti-corruption body.

He told Middle East Eye that he believed a lawsuit brought last week to the federal court by five Christian MPs would most likely be successful.

"Of course, it is a violation of constitutional principles and rights and liberties, which are granted in the constitution, so I think the federal court should reject it," he explained.

Smuggling and the black market

In regularly released assessments, Iraq is usually branded one of the most corrupt countries on Earth.

Since the overthrow of Saddam in 2003, large swathes of the economy, including the grey and black markets, have come under the control of the ascendent political parties and their allied militias.

Control over trade routes and border crossings is a source of income for many of these groups, and preventing legitimate imports of alcohol means more opportunities for organised crime.

Iraqi analyst Omar al-Nidawi suggested that while there was perhaps a "sliver of religious zeal" behind the move, the implementation was primarily about money and control.

"It will displace legitimate business owners and replace them with blackmarket operations that are either owned by or pay protection money to powerful armed militias, large elements of which have morphed into organised crime gangs after the territorial defeat of IS," he told MEE.

He also pointed out that the implementation of the alcohol ban comes shortly after a seemingly contradictory law that raised taxes on imported alcohol to 200 percent.

"This creates a bigger tax pile up for grabs, and the existence of an idle law that bans alcohol on the books created an opportunity for malign actors that have much de-facto control over official ports of entry and smuggling routes alike to displace the government and present traders with an option: pay us the equivalent of the tax, which has been made hefty by the government, or you will be out of business," he said.

Outside of the Kurdistan region, alcohol in Iraq is often already hard to come by, with most of the country's bars, clubs, and liquor stores located in cosmopolitan Baghdad.

It has long been an open secret that the various establishments in the city that do sell alcohol - particularly around the central Abu Nuwwas street and Bataween area - are either owned by or pay protection money to militias that publicly adhere to pious and sober Shia Islamist principles.

"I don't think Iraq is really going to go dry," said Fanar Haddad, an assistant professor at the University of Copenhagen and previously an advisor to former Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi.

"I think it will just work to the advantage of smuggling rings and those who control the liquor trade."

He pointed out that the example of historic prohibition, whether in the US or in other Muslim-majority countries, proved that acquiring and drinking alcohol would become more dangerous but not necessarily less widespread - and it often comes with a rise in deaths from homemade alcohol.

Another area that could potentially benefit is drug smuggling.

Iraq has in recent years been gripped by an epidemic of drug addiction, with many turning to narcotics to help them cope with the instability and lack of prospects that afflict many in the country.

Alcohol is already hard to come by in much of southern Iraq, with the likes of crystal meth and other unregulated drugs filling the gap.

"Banning alcohol will make it even more expensive, which in turn would increase the allure of relatively cheap drugs smuggled by the same militias from Iran or Syria," argued Nadawi.

Religious minorities lose out

The major losers as a result of the new legislation are likely to be religious minorities.

For many years in Iraq, licences to sell alcohol have only been issued to non-Muslims, resulting in Christians and Yazidis effectively cornering the market.

The loss of revenue as a result of the alcohol ban is likely, therefore, to be a further blow to two groups whose numbers have dwindled in Iraq since the 2003 invasion as a result of sectarian violence and instability.

Farouk Hanna Ato, an independent Christian MP and one of those bringing the lawsuit over the legislation to the federal court said the new law "contradicts the foundations of the Iraqi Constitution".

'What about non-Muslims who fancy a drink? This is curtailing social freedoms and personal freedoms in the name of Islamically-informed social conservatism'

- Fanar Haddad, analyst

"The Iraqi Constitution that emphasises individual freedoms cannot be violated,” he said in a statement last week.

So far, anecdotal evidence suggests that the numerous liquor stores around Baghdad have yet to shut up shop, despite the new law.

But, said Haddad, even if they manage to survive it certainly won't make life easier for them.

"They'll find a way around it. But as I said, this cannot be good for business in the grander scheme of things, which is why, again, I say that these sort of socially conservative measures do have authoritarian overtones and negative consequences," he added.

"I mean, it's not just about the economic consequences for Christian storeowners - what about non-Muslims who fancy a drink? Or what about the nominal Muslim who fancies a drink? Again, this is curtailing social freedoms and personal freedoms in the name of Islamically-informed social conservatism."

A complicated history

Iraq is widely believed to have been the country that invented beer, so it's safe to say its relationship with alcohol has been a long and complicated one.

Restrictions have been introduced and relaxed at various times in the country's history, usually to coincide with eras of political turmoil and stability, respectively.

The most recent legislation comes in the wake of a protest movement that began in 2019 calling for the overthrow of Iraq's political establishment.

Although that movement has, to a large extent, been suppressed, anger over corruption, the influence of foreign powers, and the lack of opportunities has not gone away.

The influence of Iran, in particular, has been a major point of contention for many Iraqis, who see their eastern neighbour as exerting disproportionate control over them through a mixture of energy and trade deals, and its funding of ideologically aligned political parties and militias.

Attempts to shut down alcohol sales in Iraq have long been seen as being modelled on Iran's own strict alcohol ban and many fear further emulation of the Islamic Republic's policies.

Ultimately, though, Bayati said the legislation was a means of distracting the public from the major issues actually affecting Iraq.

"The priority for the parliament, for the government, for all the state institutions should be focusing on the priorities of Iraqis, including combating poverty, combating corruption, elimination of non-state weapons and arms in the country, and many other priorities," he explained.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].