Saudi-Iran reconciliation: US on the sidelines dismisses China's role

China's efforts to broker improved relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia have caught the US by surprise, with officials, and members of the Washington establishment, scrambling to brush off concerns that American influence in the region is waning.

On Monday, State Department Spokesperson Ned Price said the US supported the talks "every step of the way," and downplayed China's role in burying the hatchet between the regional foes.

"This was not about the PRC [People's Republic of China]. This was about what Iran and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia committed to."

'[The] Saudis' turn to Beijing highlights just how poor the state of relations between the Biden administration and Riyadh is'

- David Schenker, former State Department official

In private, US officials - disciplined at sticking to talking points even during the strictest of background interviews - offered platitudes when asked for their thoughts on what many analysts are calling a watershed moment for the region.

"We have always encouraged dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia, a de-escalation of tensions is in our interests too, but let's see what is actually achieved," a US official told Middle East Eye.

A former US official, who happened to be with MEE when news of the agreement broke, had initially questioned the credibility of the reporting - only demurring once they saw a statement had been published by the official Saudi news agency (SPA).

Aaron David Miller, another former US official, told MEE that the "Biden administration has been downright passive-aggressive on this."

"There is no way to get around the embarrassment when you have your foremost adversary - China - brokering a deal between your supposed Middle Eastern ally, Saudi Arabia, and your nemesis, Iran," added Miller, now a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Blindsided

On Friday, Iran and Saudi Arabia clinched a deal to restore diplomatic relations and re-open embassies, seven years after ties were severed over several issues.

China's role in mediating the reconciliation has now put a spotlight on Washington's tortuous relationship with Riyadh, just as some hoped it was improving.

The Biden administration appears to have backtracked on its pledge to retaliate against the kingdom over its decision to back an oil production cut in October that Washington slammed as favouring Russia amid the war in Ukraine.

In November, the Biden administration ruled that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had immunity from a lawsuit over the murder of Jamal Khashoggi.

Meanwhile, reports about a threat against Saudi Arabia emanating from Iran late last year gave the US a chance to nod at Saudi Arabia's security concerns.

A spokesperson from the National Security Council warned in November that the US would "not hesitate to act” in defence of its partners in the region.

Saudi Arabia reciprocated. In February, Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan made a historic visit to Kyiv, where he met Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and pledged $400m in humanitarian aid to the country.

In conversations with MEE, current and former US officials pointed to the visit - the first by an Arab foreign minister - as a small, but a hard-fought win for the administration.

Biden administration officials said the Saudis kept them informed about their talks in Beijing with Iran, but David Schenker, a senior State Department official during the Trump administration said the reconciliation deal reaffirmed the downward trend in US-Saudi ties.

"This deal proves wrong those who were calling the bottom on US-Saudi ties," Schenker, who is now a fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, told MEE.

"[The] Saudis' turn to Beijing highlights just how poor the state of relations between the Biden administration and Riyadh is."

Oil-for-security

Saudi Arabia has bemoaned what it sees as Washington's diminishing interest in its security concerns and lecturing on human rights issues.

While ties have hit new lows under the Biden administration, doubts in Riyadh about the United States' staying power go back to the Trump and Obama eras.

Saudi fears were crystallised in 2019 when Aramco oil facilities came under a drone and missile attack that US officials blamed on Iran. The strikes knocked out nearly half of the kingdom's daily oil production.

"The US energy-for-security pact had been described as moribund before 2019, but after the Aramco attack even more questions were raised in Riyadh," Adel Hamaizia, a visiting fellow at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University, told MEE.

In recent years, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have faced sporadic attacks from Yemen's Houthi rebels.

A Saudi-led coalition intervened in Yemen's civil war in March 2015, aiming to restore the internationally recognised government.

But the conflict has become mired in a deadlock with Saudi forces continuing to launch air raids inside the impoverished country.

The enduring, brutal conflict has undermined Saudi-US ties, with congressional criticism growing as Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman moves ahead with plans to diversify the energy-rich kingdom's economy away from its dependence on fossil fuels.

Saudi Arabia is building a $500bn megacity along the Red Sea coast. It wants to position itself as a global tourism and entertainment hub and is pushing through new laws to poach international businesses away from Dubai.

"It's harder to achieve so much when conflict is brewing next door," Hamaizia said.

"Saudi Arabia is having a great time right now with record oil profits. But it's thinking long term and is cognizant that the Iran factor and broader geopolitical risk feeds into global investors' calculus when it comes to Vision 2030 and FDI" Hamaizia added, referring to Saudi Arabia's plan to diversify its economy and push through promised social reforms.

Cinzia Bianco, a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, told MEE that China had capitalised on Saudi Arabia’s doubts that the US could provide the security it felt it needed.

"Saudi Arabia and the US did not find a mutually satisfying new formula to replace oil-for-security," Bianco said. "That is what created the vacuum that China filled."

Economic lifeline to Iran

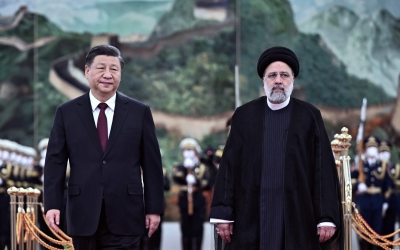

The Iran-Saudi deal is also a sign of how China's economic interests are slowly bringing it into a larger global role.

As the US continues to reduce its dependence on Gulf oil, China has become the region's biggest buyer, importing $43.9bn worth of crude from Saudi Arabia in 2021, which represented more than a quarter of the kingdom's total crude exports.

"The agreement with Iran is customer service for the Saudis," Karen Young, a senior research scholar at the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy, told MEE.

"China is their most important customer and they want to be responsive to China's requests."

At the same time, Beijing has also provided an economic lifeline to Iran, whose economy has been hit hard by Western sanctions. China is the biggest buyer of Iranian crude and has pledged to invest $400bn in the country over the next 25 years.

'The Chinese will have to lean on the Iranians to find a solution to Yemen'

- Douglas Silliman, former US ambassador to Kuwait and Iraq

"China has enormous leverage over Iran," Douglas Silliman, a former US ambassador to Kuwait and Iraq told MEE.

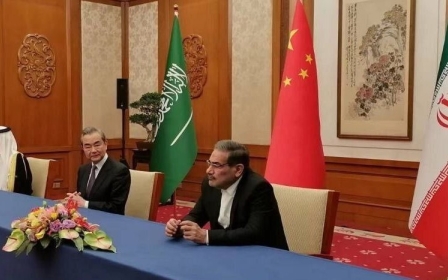

Iran and Saudi Arabia agreed to reopen their embassies and missions on each other's soil within two months and committed to non-interference in each other's internal affairs, according to a joint statement issued with Beijing.

But the main test, analysts say, will be whether Iran manages to convince its proxies in Yemen to halt attacks on Saudi Arabia.

"The Chinese will have to lean on the Iranians to find a solution to Yemen," Silliman, now president of the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington DC, told MEE. "That is going to be the main test of this agreement's success."

The deal underscores China's growing clout in the Middle East and also comes amid heightened tensions between Iran and the West over stalled talks to revive the 2015 nuclear deal and Tehran's support of Russia in the Ukraine war.

The deal is also a blow to US efforts to isolate Iran. Washington has been trying to promote greater security coordination between its Gulf allies and Israel by creating an integrated air defense system with an eye toward Iran.

'Beijing's geopolitical ambitions'

The Biden administration is trying to convince Riyadh to normalise ties with Israel, a move for which Saudi Arabia has demanded US security guarantees, access to civilian nuclear technology, and expedited arms sales in return.

Now, two parallel political tracks could be emerging in the Middle East.

Reluctant to revive the Iranian nuclear deal, the US may press Gulf states further into an alliance with Israel, while at the same time, China wants to bring them closer to Iran.

China is already working on a summit in Beijing between Gulf Arab monarchs and Iranian officials, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Analysts say far from heralding a new era of peace in the Middle East, the Beijing-brokered deal could be the harbinger of a more disordered region.

"The Middle East souk is open for business, it's a multipolar world where the Gulf states are open to the highest bidder," Miller, from Carnegie said.

China, along with Russia offers advantages that the US doesn't, such as a lack of Congressional oversight on arms sales and no questions on human rights.

"These guys are all members of the first autocrats club," Miller added.

To be sure, few are predicting that China will be able to supplant Washington’s security footprint anytime soon. As China brokers talks between Riyadh and Tehran, Washington continues to stop arms in the Gulf of Oman it says are en route to Yemen.

"China doesn't have a blue water navy," Silliman said, referring to a maritime force that can operate far from home. "It doesn’t have US readiness posture, or prepositioned troops. The US Navy still oversees the security of China’s oil flows."

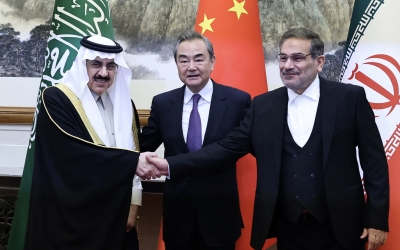

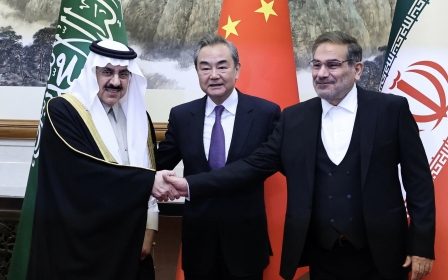

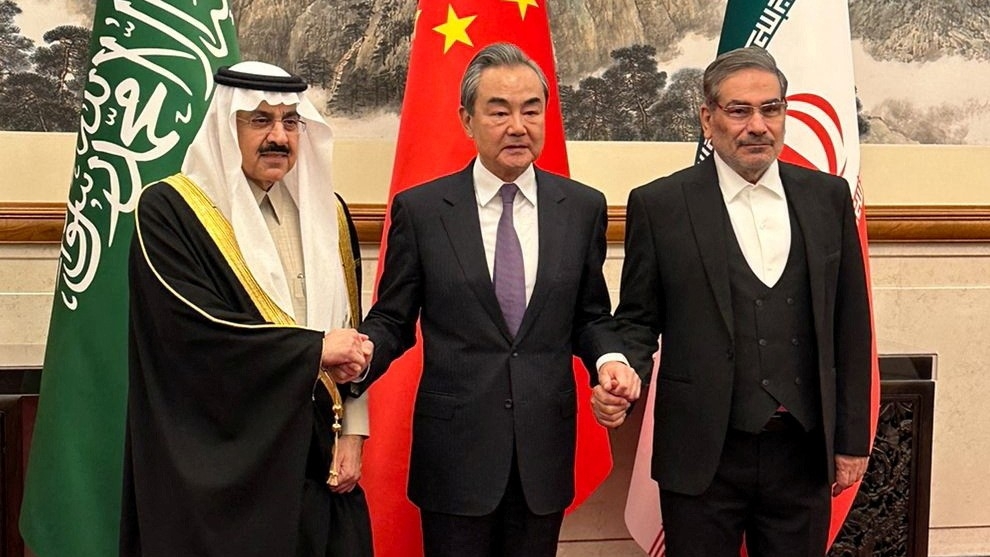

Still, analysts warn the photo of a smiling Wang Yi, China's top foreign policy official between Ali Shamkhani, the secretary of Iran's security council, and Musaad bin Mohammed Al Aiban, Saudi Arabia's minister of state, means the US better prepare for diplomatic therapy.

"The US has to recognise Beijing's geopolitical ambitions and credibility in the Gulf region and adapt its thinking to these new facts, rather than remaining hostage to outdated assumptions of its untouchable hegemony," Bianco said.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].