'We need to push back at art from the West': The Gulf as a cultural hub

For football fans visiting Qatar for the 2022 World Cup there was no shortage of museums and cultural offerings in which they could while away the hours between matches.

In addition to the Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of Qatar and the Museum of Islamic Art on Doha’s waterfront there is Souq Waqif, with its boutique galleries, and Katara, with its artist workshops and huge amphitheatre.

No fewer than three new museums are in the pipeline, including one in Lusail dedicated to hosting a huge collection of Orientalist art over four floors.

Neighbouring UAE is already home to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi Art, Art Dubai and the Sharjah Art Foundation.

More is to come over the next several years, including Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, due to open in 2025 in Saadiyat Island’s Cultural District; teamLab Phenomena Abu Dhabi; the Zayed National Museum; a multi-faith project called the Abrahamic Family House (inaugurated in March 2023), and a Natural History Museum.

The visually distinctive Museum of the Future opened in early 2022 in Dubai, a city where dozens of art galleries and spaces have launched since 2007, including the Jameel Arts Centre and The Third Line.

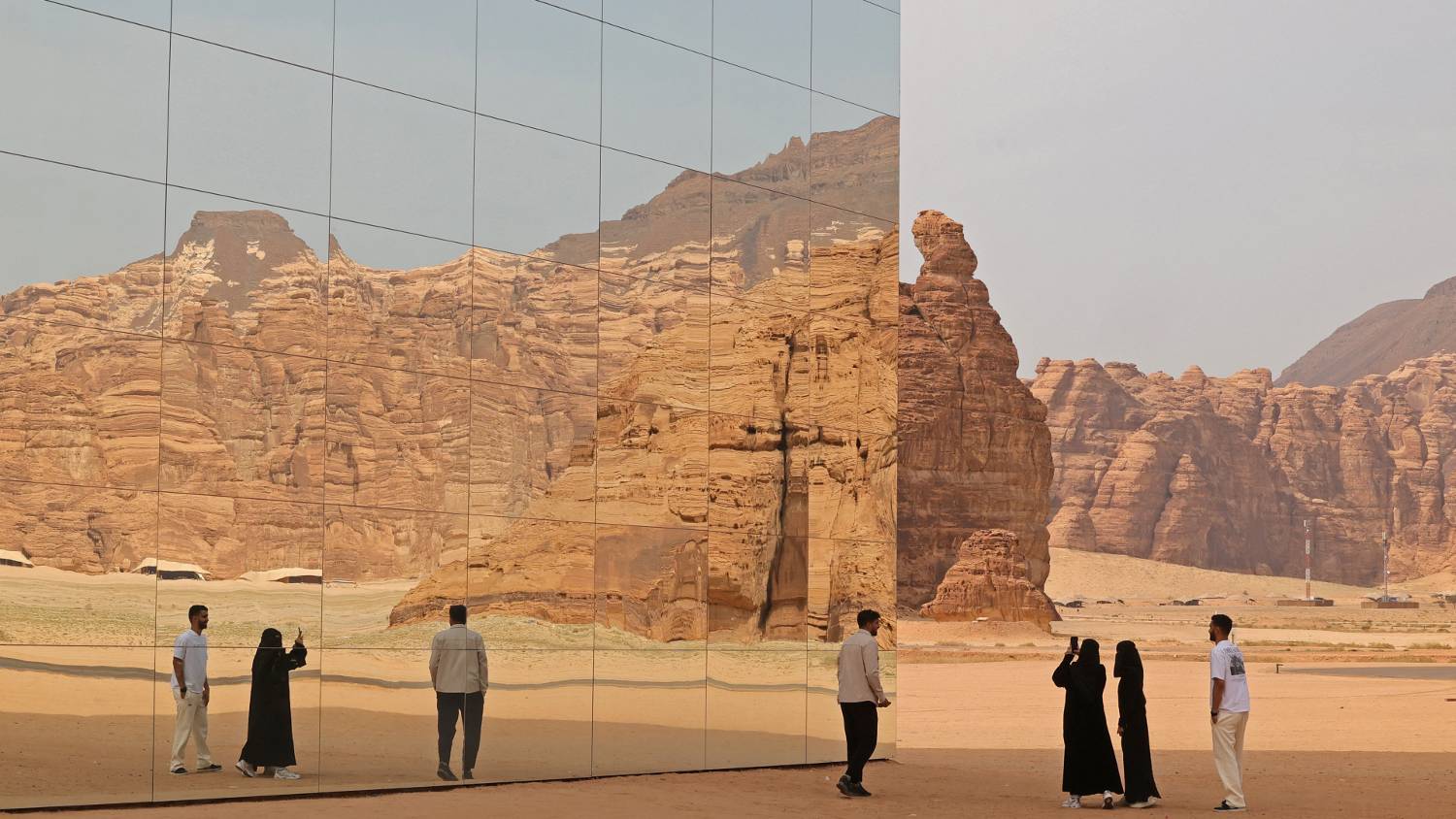

In Saudi Arabia, the first Islamic Arts Bienniale opened last January in Jeddah, and plans have recently been announced for an expansion of Paris's Pompidou Museum to the Al-Ula desert complex and archaeological site.

“FAME: Andy Warhol in AlUla” is currently exhibiting 70 celebrity paintings and prints of Andy Warhol at the AlUla Festival. These are artworks described by organisers as “most fascinating to many young people, including Saudi youth”.

In the digital space, too, new actors have made their entry, such as the online Khaleeji Art Museum, launched in 2020 by the co-founders of Sekka Magazine, Manar and Sharifah Alhinai.

These are just a few examples of a growing cultural scene across the Gulf region.

Government-led projects

The International Council of Museums (ICOM) updated its definition of museums in 2022, as “a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage".

It adds: "Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.”

Before one even glimpses their collections and programmes, museums in the Gulf have - like other significant architectural projects - begun with a building that often upholds state prestige.

The National Museum of Qatar was designed by Jean Nouvel, who won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1989 for the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris and also designed the Louvre Abu Dhabi. The Lusail Museum turned to “starchitect” Jacques Herzog of Swiss-based firm Herzog & de Meuron.

Similarly, Perspective Galleries, the Pompidou’s new project in Al-Ula, is expected to be designed by Beirut-born architect Lina Ghotmeh, who has been involved in a number of contemporary art projects in France and on the international scene.

This trend is not exclusive to museums - architect and writer Todd Reisz recalled that British architect John Harris completed Dubai’s town plan in 1960. In his recent book, Off Centre/On Stage, Reisz recontextualised before-and-after photographs away from linear myth-making and the common view of a "miraculous" journey from sand to cement.

“Khaleeji Ideology is a mode of state-sponsored futurecasting that emerged from the Gulf in the early decades of the twenty-first century,” writes Dubai-based critic Rahel Aima. “Can there be a future without government? Not here.”

Al-Ula’s transformation from desert into one of the largest museum spaces responds to a 15-year plan called Journey Through Time. Closely supervised by the Royal Commission for Al-Ula (2017), the Minister of Culture and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the plan is to create new districts to attract cultural and eco-tourism dividends in an area first inhabited tens of thousands of years ago.

Culture is key to a country’s development; it’s also a diplomatic tool. For example, France is a partner to the Royal Commission for Al-Ula via Afalula, its own agency for development within the Saudi project.

But despite strong government-backing and a feeling of limitless scope, these projects can be vulnerable to external factors.

Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, designed by prize-winner Frank Gehry to be over 10 times larger than its New York mothership, was supposed to open in 2012.

It is now anticipated to open in 2025 - a delay attributed to a range of economic and political factors, ranging from a recession to disputes over the labour conditions of migrant workers employed on the project, and various turnover of staff.

Culture for whom?

In the contemporary art scene, a challenge for these institutions will be to define their communities and audiences for long-term and meaningful growth.

“I think the question is what the goal is, and ultimately, to have something that is interesting and exciting, that needs to be located,” Holiday Powers, assistant professor in global modern and contemporary art at Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar, tells Middle East Eye.

She recalls that art communities are rarely created from the outside, but are born of artists themselves and long-standing networks.

The Sharjah Art Foundation, established in 2009 by Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, is a good example of nurturing a dynamic platform that bridges the global and the local.

It attracts artists, curators, academics, critics and other art professionals in a conversation building on the 30 years of the Sharjah Biennial, and the legacies of institutions such as the Emirates Fine Arts Society, established in 1980.

The idea of community can be subject to different interpretations: a territory, a class, a group that shares similar beliefs and attitudes.

From bringing art to local children via engaging with underserved populations, “community” can also touch upon more sensitive notions.

“There is a privileging of the local and a privileging of the national," says Dr Powers. "However, when we talk about Qatar, [the population is] only 8-12 percent nationals and virtually 90 percent non-nationals. Do you call the non-nationals in Qatar part of the local scene?”

It’s also important to stress the idiosyncrasies in play within different Gulf states. For instance, in Dubai - a main hub for the regional art market, and where a large number of foreigners live - contemporary galleries tended to be more skewed towards showing non-regional artists during the early part of the millenium. This was not as prevalent in Kuwait, where avant-garde galleries, such as the Sultan, have championed local artists since opening in 1969.

How these various institutions will interpret inclusion in their respective curatorial decisions remains to be seen.

Orientalist art in the Arabian Peninsula

One of the ways to “do things differently” could involve reinterpreting Orientalist art, a movement that peaked in the 19th century with western artists depicting sensualised and “othering” scenes from Morocco to Persia, often intertwined with colonial enterprises.

Orientalism is popular among Arab collectors and the focus of Qatar’s museum in Lusail.

Drawing on these Orientalist collections, there’s an opportunity for new art institutions in the Gulf to articulate local historiographies (rather than promote “extraterritoriality”) through the critical study of Arab and Muslim representations.

Such aspiration to localise (and often to decolonise) the scene is shared by prominent voices, such as Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, founder of the Sharjah-based Barjeel Art Foundation.

“The reality is that 95 percent of exhibitions are about other places,” he said last October, at the Culture Summit Abu Dhabi.

“Let us push art from our region against the surge of art coming to us," he added.

"We have been inundated all our lives with art from the West. We need to push back. Everybody has to push back.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].