Iran-China: Deeper economic ties could lead to showdown with Washington

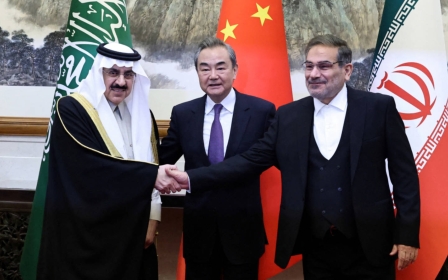

With China now playing a key role in Middle Eastern diplomacy, Beijing has become even more important to Iran's foreign policy. China seems to have retired its practice of staying above the fray of regional geopolitics, in favour of a more proactive approach that seeks to minimise tensions. In this context, detente with Saudi Arabia is a matter of secondary importance for Iran.

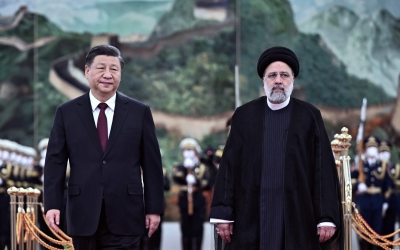

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi's trip to China last month might have helped to set the stage for Beijing's diplomatic coup, but he was also there to expand a sputtering Sino-Iranian economic relationship that is central to Iran's larger "look eastward" strategy, as well as to its approach to the West and US sanctions. For Iran, and especially for its leading conservative cadres, the country's economic ambitions and foreign policy priorities are increasingly pegged to whether this relationship with China can reach its full potential. This is still very much an open question.

The main purpose of Raisi's visit to China was to finalise agreements that would begin the process of operationalising their largely aspirational 25-year cooperation document signed in 2021. To that end, a range of new deals have been signed to bolster cooperation in various economic fields.

But the summit between the Chinese and Iranian leaders took place under the shadow of false starts and a lack of progress in recent years. Chinese investments in Iran have dropped precipitously since the US backed out of the nuclear deal: China has invested only $185m in Iranian projects since the new Raisi administration came to power. By comparison, China pledged $610m to projects in Iraq last year.

Chinese trade flows with other countries in the region, such as Saudi Arabia, vastly exceed the Sino-Iranian trade. Raisi briefly alluded to these issues in his remarks before departing for Beijing.

Chinese hydrocarbon work in Iran has also faced persistent problems. The breakdown of Chinese oil giant Sinopec's negotiations over an upstream oil project was announced while Raisi was in China.

Previous summits have resulted in the signing of memorandums of understanding that did not translate into serious action, creating the impression that Iran and China are engaging in palace diplomacy, with little actual momentum in their economic relationship.

The most important barrier towards greater Sino-Iranian ties is the fact that private Chinese firms and state-sponsored enterprises, particularly those with significant exposure to western markets, do not have the same appetite to ignore US sanctions as the Chinese government or some "teapot" oil refiners do. Sanctions are a major factor in Sino-Iranian economic ties.

Iran even has $20bn in funds frozen in Chinese banks due to western sanctions. The Chinese government is now reportedly allowing Iran to tap these funds, as part of an incentive package preceding the Iran-Saudi detente. Considering this move is unlikely to have been authorised by the US Treasury, it will be interesting to see how this will be structured, and whether it will attract scrutiny from Washington.

But Iranian conservatives don't merely blame China for the aforementioned false starts. A persistent criticism of the Rouhani administration was that it failed to recognise the importance of developing ties with eastern partners, China in particular, because it was too focused on re-establishing economic ties with the West through the nuclear deal. Such criticisms have originated from conservative officials and members of the business community.

The notion that Iran's trade must be balanced, building western and eastern ties simultaneously, was well represented by the Rouhani administration. This notion of balance has as much to do with economic development goals as it does with concerns over sovereignty and the possibility of becoming overly dependent on China.

If China is Iran's only investor and economic partner, wouldn't even limited cooperation generate dependency? This issue seems to have been at least one contributing factor to the limited appetite of the Raisi administration to build economic ties with China, while Iran's economic relations with the West remained anaemic.

Economic uncertainty

Raisi's rhetoric about rediscovering economic opportunities in the East has largely focused on addressing this conservative criticism. The Raisi administration has made the reduction of tensions with Arab Gulf states a priority, and it has been partially successful in this goal - a strategy that also likely aims to lower the Chinese perception of risk towards further engagement with Iran.

Yet, while some Iranian conservatives hoped that Raisi's efforts and East-facing approach would result in new Chinese investments and increased trade, that wish has not materialised. They are now having to push back against a perception that even elevation to membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation is largely symbolic and will not result in many tangible benefits for Iran.

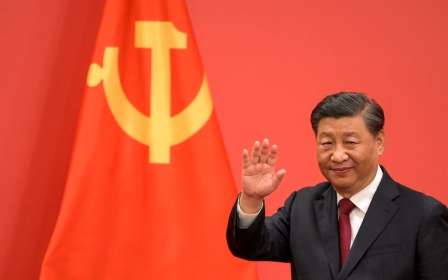

The current impression is that despite Chinese government rhetoric, China's economic relations with Iran are based on the individual calculations and interests of various economic actors in China, most of whom are easily influenced by sanctions. In this sense, China's desire to confront Washington's economic coercion tactics, or to forge some form of balancing bloc against the US, is far more limited than previously thought.

The question for many Iranian conservatives will be whether China is interested in actively confronting the sanctions regime and building a more comprehensive economic relationship with Iran, or whether it views this as unnecessary. If the latter is true, Sino-Iranian ties will grow very slowly, if at all, and be further marginalised by increasing ties between China and Iran's regional rivals. This would translate into significant economic uncertainty in Tehran, considering Iran's economically isolated state, and likely lead many to downgrade their impression of Chinese economic power and strategic autonomy.

The Raisi administration and many in Iran who advocate greater Sino-Iranian ties - including many reformists - believe that Iran needs to build strong economic relations with China as a means of thwarting western sanctions. This does not mean they do not wish to re-enter the nuclear deal, but they believe that solid economic relations with China would bring Iran leverage in its diplomatic interactions with the West. Much of Iran's foreign and economic policy is essentially premised on this framework.

Obviously, the current level of Sino-Iranian economic relations is not enough to prove that notion viable. There will be significant attention on whether the agreements signed in Beijing during Raisi's visit will actually be implemented. Whether these new deals translate into practical action will be the most important test yet for Sino-Iranian relations, and it will have a profound impact on their trajectory moving forward.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].