How Ramadan in Gaza became a time of mourning, not celebration

As Muslims around the world usher in the holy month of Ramadan and all its trappings, Palestinians brace themselves for what has become Israel's favourite holiday tradition: a potential new round of attacks on Gaza following a surge of settler violence and military raids in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Without hesitation, every single person I interviewed expressed the same fear: everything points to a new round of escalation

Palestinian anxieties have only increased since the new far-right and racist Israeli government took power, which has led to the killing of at least 88 Palestinians, including 17 children, since the start of the year.

As others have noted, Israel has already killed five times as many Palestinians as it had by this time last year - with Israeli officials celebrating and vowing even more.

The Ramadan-themed assaults on Gaza generally follow the same formula: the Israeli government restricts Muslim worshippers' access to holy sites in Jerusalem or issues eviction notices to forcibly expel Palestinians from their homes, as they do in Sheikh Jarrah and many other villages. Palestinian resistance groups in Gaza then respond to these provocations by protesting at the eastern borders, using incendiary balloons or firing homemade rockets - actions that are met with brutal bombings of densely-populated areas.

Recent provocations

Naturally, it didn't take long for the Israeli government to begin instigating war. On the first Friday prayer in Ramadan, Israeli forces installed roadblocks and prevented hundreds of Palestinians from entering Al-Aqsa Mosque, while helicopters and drones circled above the Dome of the Rock.

On the fourth night of Ramadan, Israeli forces assaulted Palestinian worshippers, interrupting their special prayers, and forcing them out of Al-Qibli Prayer Hall in the Al-Aqsa Mosque complex.

Since this is very much a deliberate strategy by the Israelis, talks of how the government would treat Palestinians during the holy month had already been covered in various media outlets.

Earlier this month, right-wing National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir made clear his intentions to inflame tensions by demanding that Israeli police continue demolishing homes in East Jerusalem during the month of Ramadan.

Reportedly, Israeli security services warned Ben-Gvir that this practice - a war crime the government commits year round - could lead to unrest in the West Bank, as what happened two years ago during Ramadan.

Even senior police officers criticised Ben-Gvir's belligerent approach towards Muslims during the holy month. "We're on the eve of Ramadan, everyone's trying to calm things down, but he wants to inflame them. His behaviour is reckless and amateurish", one recently told Haaretz.

Ben-Gvir, whose racist incitement at Al-Aqsa Mosque was widely condemned, further criticised Israeli security officials for their plan to prevent Jews from entering Al-Aqsa's courtyard for 10 days as "absolute madness and surrender to terrorism".

Following last month's pogrom in Huwwara and ongoing settler attacks - and with the wheels already set in motion for possible war - I decided to speak to Palestinians from different areas in Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem about what the month of Ramadan has come to mean for them.

Without hesitation, every single person I interviewed of different ages, experiences, and fields of work expressed the same fear: everything points to a new round of escalation, much like the ones before it, except now it will be carried out by a leadership whose genocidal aims are even more pronounced.

Gaza still weeps

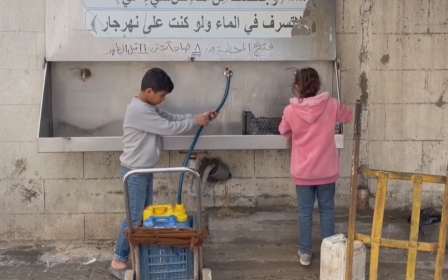

Walking along the streets of Gaza is a war-weary population, whose facial expressions convey deep anxiety and trepidation about the coming weeks. Ramadan, supposedly a month of peace and religious celebration, is remembered in Gaza as a time of profound grief and loss. Many who have experienced this death cycle wonder aloud if what awaits them is a time of worship and family gatherings or a new war with more death and destruction.

Hundreds of families still cry over loved ones killed in Ramadan of 2014 during Israel's 51-day bombardment of Gaza, which claimed 2,251 Palestinian lives, nearly half of whom were women and children.

During the 2014 war, my own family had to escape our house as bombs neared. The sight of a mass exodus of people in my neighbourhood fleeing their homes for safety reminded me of stories I grew up hearing of the Nakba, when the Palestinian people, carrying whatever they could, escaped for their lives. Decades later, I had the same thoughts as my grandfathers did in 1948 - that our lives are meaningless when facing a war machine.

Israel's 2021 assault on Gaza began just days before the beginning of Eid al-Fitr, killing hundreds of people and once more terrorising fasting Palestinians. The devastation of this war continues to inflict misery and grief on the victims' families, the injured and the thousands of displaced people whose houses were destroyed and never rebuilt.

Indeed, what often gets forgotten when the world's attention is no longer fixed on the horrific scenes from Gaza, and long after the martyrs are buried, are the survivors with no means to survive. Several families whose houses were bombed are still living in schools and caravans with limited access to food, water and basic resources provided by charitable organisations.

"Living in peace has never been the norm for us, even during Ramadan," said Mohammed (a pseudonym), a father of four who has lived with his family in a small caravan since their home was destroyed two years ago. "I can no longer even afford to purchase lanterns for my children."

Unsurprisingly, Mohammed wanted to remain anonymous because, like tens of thousands of other unemployed men in Gaza, he wanted his application to work in Israel to be approved.

Missing family

One of the most tragic stories I often think about is the horrific bombing of a family home in May 2021, which took place in the immediate days after Ramadan. It is the story of Zainab al-Qolaq, who instantly lost 22 members of her family in the Al-Wahda Street Massacre.

Forty-two people were killed in the attack, including 16 women and 10 children, and 50 more were injured that night - entire families were wiped out from the civil registry.

"Ramadan, for the people of Gaza, is linked with missing loved ones. I spend my days fasting worried about who I'll miss next," Zainab said.

Before the massacre, Zainab was an artist who used to paint life: the sea, seagulls, trees, snow, horses, homes and rural roads. But, after that day, she only paints death, which engulfs her like a daily nightmare.

"Losing [my family] has left an ever-expanding gap in my heart, while the fires of longing to see them again burn deep in my soul," Zainab expressed on her social media, commemorating the massacre.

When I asked Zainab questions about the family she lost, in a trembling voice expressing immeasurable pain she expressed doubt in her ability to answer since the questions remind her of her missing family.

"How can I celebrate Ramadan with family members missing from the dinner table?"

Despite war

I was once again walking on a busy street in Gaza with heavy thoughts of how the experience of Ramadan for Palestinians has become fraught with anxiety. I wondered about what memories and possible trauma we might carry by the end of this month.

The children's joy was a reminder of how our simple existence is a form of resistance and how, in the same vein, Palestinians resist in order to feel alive

Things that some people take for granted such as visiting relatives and breaking fast together become impossible in times of war. Instead, families must begin or break their fast to the sound of massive explosions by Israeli warplanes near their homes. Other activities, such as going for walks, shopping, attending nightly prayers or gathering in community with others - the elements that make Ramadan a festive time of the year - might land a person in the Israeli "bank of targets".

In a BBC article, the children of Gaza - who make up half of the total population - are described as having grown "used to death and bombing". They receive no protection, and instead of experiencing joy during Ramadan - buying lanterns and lighting fireworks - they must endure Israeli warplanes, bombs, trauma or even death.

I was deep into these bleak thoughts when suddenly a group of children ran past me carrying Ramadan lanterns. At that moment, the sight of their smiles and excitement inspired feelings of hope in me. Their joy was a reminder of how our simple existence is a form of resistance and how, in the same vein, Palestinians resist in order to feel alive.

Despite the ever-looming threat of war, Ramadan continues to be a time of celebration in Gaza. String lights and bright colours adorn the streets illuminated by fires lit through the night, and around which people gather, eat, laugh, share stories, recite Quran, and perform rituals and group prayers until dawn.

Some refugee camps have even organised large potluck gatherings for both Suhur and Iftar - a community gathering that means everything to the people there.

"We will celebrate no matter what happens next," many people told me as they shopped for decorations around the old market.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].