The curious case of Flight 422: Why was the series on hijacked Kuwaiti airliner pulled?

Kuwait has one of the oldest Arab TV industries, however elementary direction, hammy performances and lack of rhythm make its shows unexportable outside the confines of the Gulf region.

Loudly expressed governmental and societal reservations about serials on hot-button issues such as Saq Al Bamboo, about the children of mixed-race relationships, and Um Harun, on the country’s little known Jewish community, are common.

What happened with Flight 422 was unprecedented, however.

The multi-million dollar production bankrolled by Saudi Arabia’s entertainment behemoth MBC is a dramatisation of the hijacking of the eponymous Kuwaiti flight by Hezbollah fighters in 1988, which resulted in two deaths.

The incident lasted 16 days and is ranked as one of the longest skyjackings in history.

A few days after the first three episodes of the show were aired on 28 February, a widespread Kuwaiti campaign against the series erupted on social media.

Some viewers, along with a number of directors and politicians, accused the producers of “falsifying history” and “insulting Kuwait’s symbols”, including its late leaders.

Kuwait’s Ministry of Information issued a statement expressing dissatisfaction with the show and calling on MBC to suspend broadcast and streaming.

Shortly after, Flight 422 disappeared from Shahid, MBC’s streaming arm and one of the region’s most popular streaming services.

Following the suspension, the ministry released a second statement, thanking MBC for responding to its grievances and stressing the importance of solidarity between Gulf states.

To date, Flight 422 is unavailable on Shahid or any other streaming platforms but the first three episodes have been widely pirated. The remaining three episodes remain unseen.

For viewers unacquainted with Kuwait’s cultural and political landscape, it’s near impossible to determine the cause of the controversy by watching the series.

Navigating the thorny geopolitics of the late 80s, Flight 422 commences with a declaration that those depicted are fictitious characters, inspired by, if not based on, the real passengers.

This allows the showrunners to build a tense drama with colourful characters, tension and dark humour that pad the heaviness of the politics.

The show’s British director, Ashley Pearce of Downtown Abby fame, does not omit the real-life political players involved in the hijacking.

Some of the figures in the first three episodes include Yasser Arafat; Hezbollah leaders Mustafa Badreddine and Imad Mughniyeh; and, most controversially, the late emir of Kuwait Jaber al-Ahmad Al Sabah, and Saad al-Salim Al Sabah, its then prime minister.

Early Hezbollah

Contrary to the statement by the Kuwaiti Ministry of information, Flight 422 adheres to the facts to a large extent.

Hezbollah, which was founded by Iranian Revolutionary Guards in the early 80s, as well as its patron, Iran, are the chief antagonists of the story.

Kuwait found itself in the line of fire for its support of Iraq during the Iran–Iraq War, becoming a key target in Hezbollah’s operations.

On 12 December 1983, bombers targeted the embassies of France and the US in Kuwait, along with Kuwait City’s airport and a petrochemical plant, resulting in five deaths.

Badreddine, a Hezbollah bombmaker, entered Kuwait prior to the bombings and was arrested by the Kuwaitis along with 17 others on 13 December.

The Kuwait Airways Flight 422 hijacking from Bangkok was carried out by Imad Mughniyah, Badreddine’s Hezbollah comrade.

Mughniyah and the hijackers had one demand: free Badreddine and the others detained in connection with the 1983 bombings.

That’s the background against which the events of Flight 422 unfold, with four plotlines comprising the backbone of the series.

They include the events onboard the hijacked plane; Saad al-Sabah’s behind the scenes string pulling to free the hostages; Badreddine refusing to divulge information about the bombings under interrogation; and the pairing of a journalist and an undercover officer to gather intelligence.

Not princely

The series undeniably delves into treacherous waters: from the forgotten history of Kuwait’s standoff with Hezbollah and Arafat’s relationship with the group, to the impact of the 1983 bombings on Kuwait’s Shia community and Algeria’s role in facilitating the eloping of the hijackers.

It was not the show’s political stand that drew the ire of the Kuwaiti authorities. There’s nothing remotely offensive about the depiction of the late Kuwaiti leaders.

On the contrary, Jaber and Saad al-Sabah are positively depicted: the former as an upright saintly figure prepared to sacrifice himself for his people; the latter, a shrewd but headstrong mover ready to grab the Hezbollah bull by its horns.

But both the authorities and a segment of the public did not like what they saw - literally speaking.

As ridiculous as it sounds to the western reader, the Kuwaitis were offended by the bad make-up and ostentatious performances of the actors playing their iconic leaders.

Nothing in the behaviour and overall characterisation of the two were found specifically objectionable; the Kuwaitis were outraged by the imperfect appearance of the Kuwaiti actors… by Jaber’s goatee and Saad’s unwavering stare.

The term used constantly in criticism is “The Princely Self” - the duty to protect the emirs from depictions that can never capture their wholesome dignity.

Outlandish as this may seem, the Flight 422 debacle is in tune with a society and culture that has been isolated for more than 30 years.

Despite being granted civil liberties and having a democratic parliament rendering the country the most politically progressive Gulf state, censorship has worsened since Kuwait’s heyday of the 1970s when it was a leading producer of TV content in the Arab world.

Critics and scholars have attributed this decline to the isolationism and political neutrality Kuwait has staunchly adopted since the early 90s, and to the lingering trauma of the devastating Gulf War that threatened the country’s existence.

Despite its bottomless wealth, Kuwait, unlike the UAE and Saudi Arabia, has steered from playing an instrumental role in the region’s ceaselessly turbulent politics.

Any critical thinking, any spark that could stir social or political debate, has been instantly extinguished.

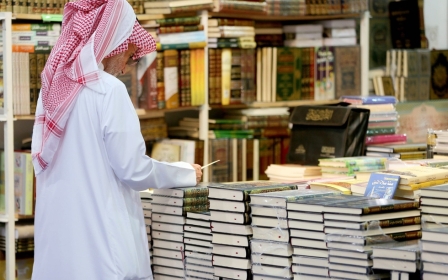

The Kuwait Book Fair, one of the largest in the region, is a case in point. More than 5,000 titles have been banned in the country for nearly a decade, including Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Laws were only relaxed in 2020 following public pressure.

Touchy subject matter

Irrespective of its characters, Flight 422 was always bound to stir controversy inside and outside Kuwait.

The series wears its anti-Iran sentiment on its sleeves, opening its credits with the statement that in the 80s Iran was “spreading its revolution… including Iraq.”

Hezbollah hijackers are portrayed as brutish, merciless fanatics, with no backstories. Then again, with half the series unseen, it’s impossible to judge the incomplete characterisation on offer.

The show hints at the discrimination against Shias in Kuwait and the hostile social stance against inter-sectarian marriage through the character of a Sunni passenger, who was ostracised from his family after marrying his Kuwaiti Shia wife, and who is now having an affair with an Alawite. This subplot alone would have got the series in hot water with the Kuwait authorities.

Curiously, and by comparison, there was no Palestinian outcry against the unflattering depiction of Arafat. In the most hair-raising moment, Arafat, who cordially offers to help Saad al-Sabah, gets a scolding from the former Kuwaiti prime minister. “Do not interfere,” the Kuwaiti sternly warns, “This is none of your business.”

The show implies that the Kuwait royal family blamed Arafat for his role training young Hezbollah fighters alongside the PLO.

Whether the call between Arafat and Saad al-Sabah points to developing anti-Palestinian sentiment in the show is also unknown since it’s unclear what happens in the later three episodes.

Hezbollah silence

Another element that incited ridicule and annoyance is the inaccurate dialects. The Lebanese dialect spoken by the hijackers is inconsistent and lacking the tonality of Lebanese Arabic.

A quick survey of the cast - mostly Palestinian and Saudis - explains the roots of the error. But according to sources, Lebanese actors were apprehensive of joining the show, fearing a Hezbollah backlash at home.

Strangely enough, Hezbollah were silent on Flight 422. And given the swift response by MBC to the statement by the Kuwaitis, it is not implausible that the Shia movement could be behind the suspension of the show.

Flight 422 was the second series to be banned by Kuwait in March.

Shortly before the suspension, the Ministry of Information terminated the broadcast of Al Sageen al Nassab (The Swindler Prisoner), a Tinder Swindler-like Kuwaiti series chronicling the real-life exploits of a conman who assumed the identities of prominent public figures to scam wealthy women.

A storm similar to the one that greeted Flight 422 was replicated on social media, with users accusing the show of “insulting the Kuwaiti society” and “tarnishing the image of Kuwaiti women”.

In the latest escalation, the Kuwaiti cast and crew involved in both series have been referred to the public prosecutor and may face the withdrawal of their work permits.

The joint reaction to the two series conveys the hermeticism of a society enveloping further unto itself: a society that is no longer tolerant of criticism or capable of self-reflection.

The referral of the Kuwaiti personnel to the public prosecutor is an indication of another steep lowering of the bar for creative freedoms.

The case of Flight 422 is more convoluted, and far more alarming. MBC and Shahid - a venture largely controlled by the Saudi government - dominate Arab entertainment, dwarfing Netflix which continues to stutter with its operation in the region.

External pressures

Run by Lebanese journalist Ali Jaber, MBC, and Shahid in particular, have shown increasing boldness and edginess in the series they have produced over the past few years. Unafraid of tackling taboos and pushing a progressive agenda, Shahid has defied the odds, surprising critics and viewers at every step.

But MBC and Shahid remain under the control of the Saudi government and thus vulnerable to external influences.

Flight 422 was not the first production shelved by the network. Last month, similar uproar met Mu'awiya, a $75m historical epic directed by Palestinian-Egyptian filmmaker Tarek Alarian. The show was based on the life of Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, the first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate.

These myriad bans and suspensions raise question marks about how free Shahid truly is

After being urged by the Iraqi Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr not to broadcast the show, the Iraqi media commission demanded MBC withdraw Mu'awiya from its Ramadan roster. MBC promptly complied and will not air the show in Iraq.

Menawara Be Ahlaha (Enchanted, With its People), the highly anticipated first series by Egyptian filmmaker Yousry Nasrallah, faced similar annoyances last year, albeit for more trivial reasons.

A week before the streaming date of the series, cast member Bassem El-Samra publicly attacked Turki al-Sheikh, an adviser to the crown prince and the chairman of General Authority for Entertainment, for his disparaging comments regarding Egyptian comedy icon Mohamed Sobhi.

Days later, the show’s trailer vanished from Shahid and the series did not stream on its scheduled time. Only after El Samra made a public apology to Sheikh was the series allowed to stream a month later.

These myriad bans and suspensions raise question marks about how free Shahid truly is.

Flight 422 is laced with anti-Iran sentiment that now feels ill-timed after Saudi Arabia’s recent truce with Iran, the state’s main regional rival.

The outlandish case of Flight 422 ultimately transpires as a cautionary tale of both the shrinking freedoms of an insulated society refusing to confront itself and the precarity of producing political stories under the watch of autocratic regimes.

Given the heightened interest the cancellation of the show has generated, it wouldn’t be inconceivable for Flight 422 to resurface sooner or later, albeit with radical alterations that would appease the Kuwaitis.

The fact that such a big production could be abruptly withdrawn in such a fashion illustrates the narrow parameters under which MBC and Shahid are forced to operate.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].