From Haza Al Masaa to Fawazeer: The best ever Ramadan TV series from across the Arab world

For many years, the Ramadan series label was shorthand among film industry types for hammy acting and crude aesthetics. But even in the early years of Arab TV, there was more to serialised drama than its later reputation implied.

Ramadan series date back to the 1960s, when the region’s first TV drama, Hareb Min el-Ayyam (Escaping from Time), broadcast from Egypt in 1962.

A mystery thriller about a run of robberies in a small village, director Nour El Demerdah’s creation took the region by storm, establishing Egypt as the most prominent producer of serials for the next four decades.

Today, the Arab TV landscape bears no resemblance to its modest origins. Ramadan has steadily become the biggest, most lucrative TV season of the year, boasting the region’s biggest talents and seemingly endless advertising money.

Big money and competition from American shows forced producers to reinvent the Ramadan serial. Production values improved, storytelling grew edgier and performances become more refined and less stagey.

The long-standing 30-episode structure - an episode for each day of the month - remains largely intact, despite the recent rise in the 15-episode format.

We continue to await a golden age of Arab TV: censorship is more stifling than ever, writing remains patchy and direction is inconsistent.

That said, with producers in North Africa and Iraq entering the scene and streaming platforms attracting a younger audience, Arab productions are on an upward trajectory - constantly pushing boundaries, while providing an indispensable window into the mores and evolving values of their respective societies.

For the novice audience, navigating the vast landscape of Ramadan serials is a challenge, especially with a lack of English subtitles available.

But things are changing in that regard too. While not producing any Ramadan series of its own, Netflix has begun to acquire recent Arab hits, such as Mohammed Ali Road and The Sculptor.

Regional rivals like Shahid and OSN also offer classic shows with English subtitles, making it easier than ever for curious viewers to dip their toes into the delirious universe of the Ramadan series.

The best place to start: Egypt

Rather than starting chronologically, the best access points to get into Ramadan serials are relatively recent shows.

Despite more regional competition today, Egyptian serials remain the most accomplished, most bankable, and most watched. And so it is impossible to start anywhere else.

The best entry point is 2017’s Haza Al Masaa (Later Tonight), Tamer Mohsen’s daring, multi-character drama, considered by numerous critics - including this writer - to be the best Ramadan series of the century.

It is the finest work to date by Mohsen, who is one of the most distinctive voices in Arab drama.

This disarmingly intimate study of class, sex and the crisis of masculinity is the most authentic work to emerge in Egypt since the 2013 coup.

Strikingly shot and boasting pitch-perfect performances by Eyad Nassar, Muhammad Farrag, Ahmed Dawood and Asma Abul-Yazid, Haza Al Masaa remains unmatched in its candour and authenticity - the benchmark for every subsequent relationship drama.

Equally daring and aesthetically pleasing is 2016’s Afrah AlQoba (The Joys of Qubba), Mohamed Yassin’s adaptation of Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz’s 1981 novel of the same name.

Set in the early 1970s, the story centres on a group of theatre actors who realise that the play they’ve been hired to perform is based on their own lives.

Told from multiple perspectives and imbued with magical realism, Afrah AlQoba is an austere period drama set in the decadent Cairo of the early Sadat era.

The city is drowning in opium addiction, familial dysfunction and moral corruption.

Entrancing in its atmosphere, the show is Yassin’s crowning achievement, although his similarly bold murder mystery Moga Harra (Heatwave), made in 2013, is also worth watching.

More lighthearted is A Girl Named Zat, Kamlah Abu-Zikri’s 2013 adaptation of Sonallah Ibrahim’s iconic 1992 novel. This BBC co-production is a panorama of Egyptian life from the 1952 revolution until the 2011 uprising, as seen from the point of view of a middle-class woman.

Like the source novel, Zat is full of shrewd commentary and astute observations on the events that changed the face of Egyptian society. It is possibly the most low-key entry on this list, but its warmth and humanity render it no less important.

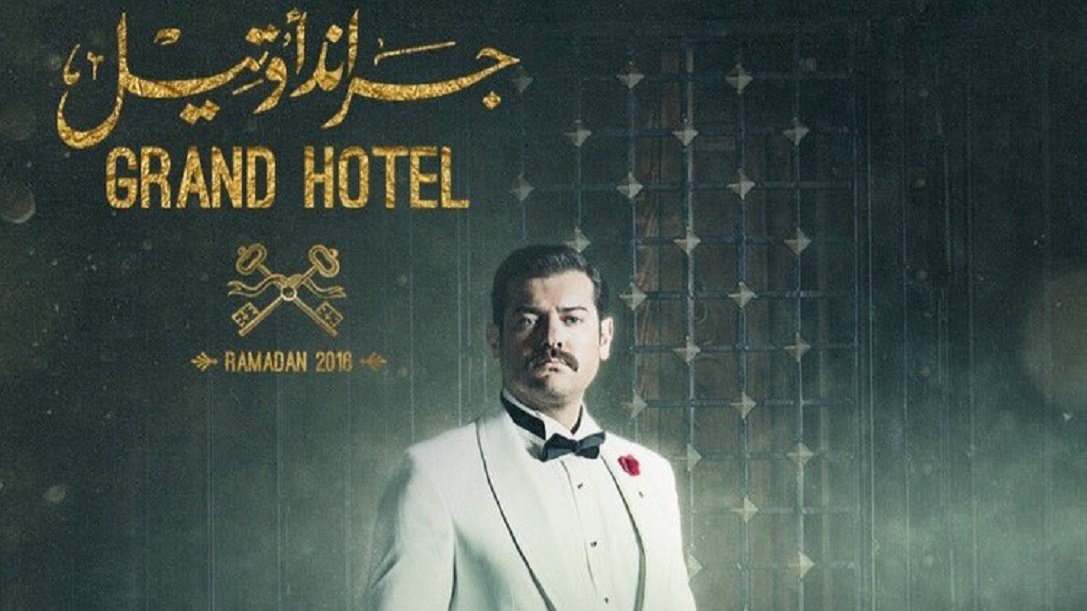

For many initiated western viewers, their introduction to Arab TV began with 2016’s Grand Hotel, Mohamed Shaker’s smash hit adaptation of a 2011 Spanish series of the same name.

Set in 1950s Aswan, this romantic mystery follows a young man who travels south in search of his missing younger sister.

Devoid of social commentary, Grand Hotel is nonetheless a highly engaging story, bolstered by the sweeping romanticism of writer Tamer Habib and Shaker's strong sense of space.

The series made headlines in 2018 when it became the first Egyptian series to be acquired by Netflix. It remains one of the few Arab TV works with a sizeable audience internationally.

The best shows to binge

With the new millennium, Egyptian TV dominance came under threat from the rise of Syrian historical dramas.

Egypt’s offerings had grown stodgy by the late 90s, hampered by dull direction that had failed to evolve in decades.

Showered with generous state funds, Syrian directors blew new life into the Ramadan TV tradition. Lofty dialogue, epic storytelling and subtle acting helped Syrian dramas stand out against the histrionics of contemporary Egyptian performances.

During the 2000s, Syria produced numerous acclaimed works, the most famous of which are the historical dramas of the late Hatem Ali, whose blend of history with melodrama produced the ideal form for bingeing.

Of the many excellent series he produced, three stood out. In the 40-episode Al Zeer Salem, produced in 2000, Ali explored pre-Islamic Arabia through the poet and warrior Abu Layla al-Muhalhel during the Basus war (494-534).

From the rugged landscapes and adroitly choreographed battles to the emphasis on jahiliyyah poetry and customs, Ali’s most cherished work remains a touchstone in Arab historical dramas.

Edgier in themes and tone is the 2005 Mulouk Al Tawa'ef (Kings of the Sects), the third and darkest part of a trilogy that chronicled the Muslim conquest of Spain.

A Tudors-like drama charting the fall of the Spanish Umayyad dynasty, Ali’s last great Syrian series is a wild monster - a lavish production mounted with remarkable panache. The never-ending conspiracies, double-crossings and power struggles remain eerily relevant in the contemporary Arab political landscape.

Ali’s greatest work could well be 2004’s Al-Taghriba al-Filistinia (The Palestinian Alienation), a dramatisation of the Palestinian affliction as experienced by a rural family from the British Mandate in the 1930s until the 1967 war.

Layaly El Helmeya is the ultimate Ramadan soap opera - a compelling amalgam of insightful social documentation and pure trash

Imposing in its scope and emotion, this is the definitive Arab series on the Palestinian story: a thorough recreation of an historical epoch seldom tackled on TV.

The ultimate bingeable Ramadan series is Layaly El Helmeya (Al Helmeya Nights), broadcast from 1987 to 2016, the long-running Egyptian drama recounting Egypt’s modern history, from the waning days of the monarchy to the 2011 revolution.

Featuring some of the most iconic characters in Arab TV and unabashedly sensationalist in its narration, Layaly El Helmeya is the ultimate Ramadan soap opera - a compelling amalgam of insightful social documentation and pure trash, penned with effortless nonchalance by Osama Anwar Okasha, the grandmaster of Egyptian TV drama.

Not everything in it works, and the narrative grows unbearably cumbersome by season five, so better to stick to the first four seasons.

Comedies with political insight

Comedies have long been a Ramadan staple, dating as far back as 1972 with the Egyptian classic Adat W Takaleed (Customs and Traditions). Evergreen and no less popular than drama, Ramadan comedies have endured acute transformations since - from the hit-and-miss sketch shows of the 90s to the ill-suited sitcom craze of the 2000s.

Unlike drama, TV comedies are local affairs, particular to their respective culture and difficult to translate regionally, let alone internationally. Every other year, a Ramadan comedy hit does succeed in transcending cultural barriers, helped by biting political commentaries.

Pre-war Syria produced remarkable comedies, but nothing stood out as much as Laith Hijo’s De'ah Da'iah (The Dayaa District, 2008-2010), a buddy comedy set in the coastal city of Latakia that pits nature and traditional living against modern urbanity.

Hilarious characterisation aside, what elevates the show is its audacious and defiant political subtext, which touches on structural corruption, governmental negligence and forced migration. Running for only two seasons, De'ah Da'iah is the last important Syrian comedy.

More controversial, at least in its first seasons, is Tash ma Tash (No Big Deal), which has been running since 1992. Saudi Arabia’s most recognisable and longest-running TV show is a comedy that follows the misadventures of two rabble rousers (played by Nasser Al-Qasabi and Abdullah Al-Sadhan) in a country torn between modernity and archaic tradition.

Unlike Syrian and Egyptian shows, the humour of Tash ma Tash does not always translate well, while direction is largely elementary. But the social criticism on display was hair-raising for its time, targeting clergymen, bureaucracy and nepotism.

The show lost its mojo after it was acquired by MBC in 2005, swiftly becoming a vehicle for the Saudi regime to disseminate its agenda.

Equally political and more relevant is Watan ala Watar (A Country Hanging by a Thread, 2009 to present), Palestine’s most watched TV series ever. Its denunciation of everything from factional feuding to ineptitude, and the impact of political stagnation on the individual, has frequently landed it in hot water with local authorities.

The first three seasons are the sharpest, and even though its critical tone has been somewhat tamped down, Watan ala Watar remains an imperative part of the otherwise impoverished Palestinian television scene.

Egypt has produced its fair share of comedy gems, so many it's difficult to narrow the choice down to single digits. A particular favourite is Saken Ossady (Next Door Neighbour, 1995), Ibrahim Al Shaqanqiry’s incisive social satire about the odd rivalry of two neighbouring families representing the old, dying bourgeoisie and the nouveau riche.

Containing none of the sagging sentimentalism common in Arab social comedies, the Yousef Owf-penned series is hilarious from start to finish - acerbic yet endearing, clever yet unpatronising.

It’s also one of the most vivid documents of the Mubarak era - of the class disjunction, Kafkaesque red tape, and the cannibalistic proliferation of consumer culture.

The escapism of the 'Fawazeer'

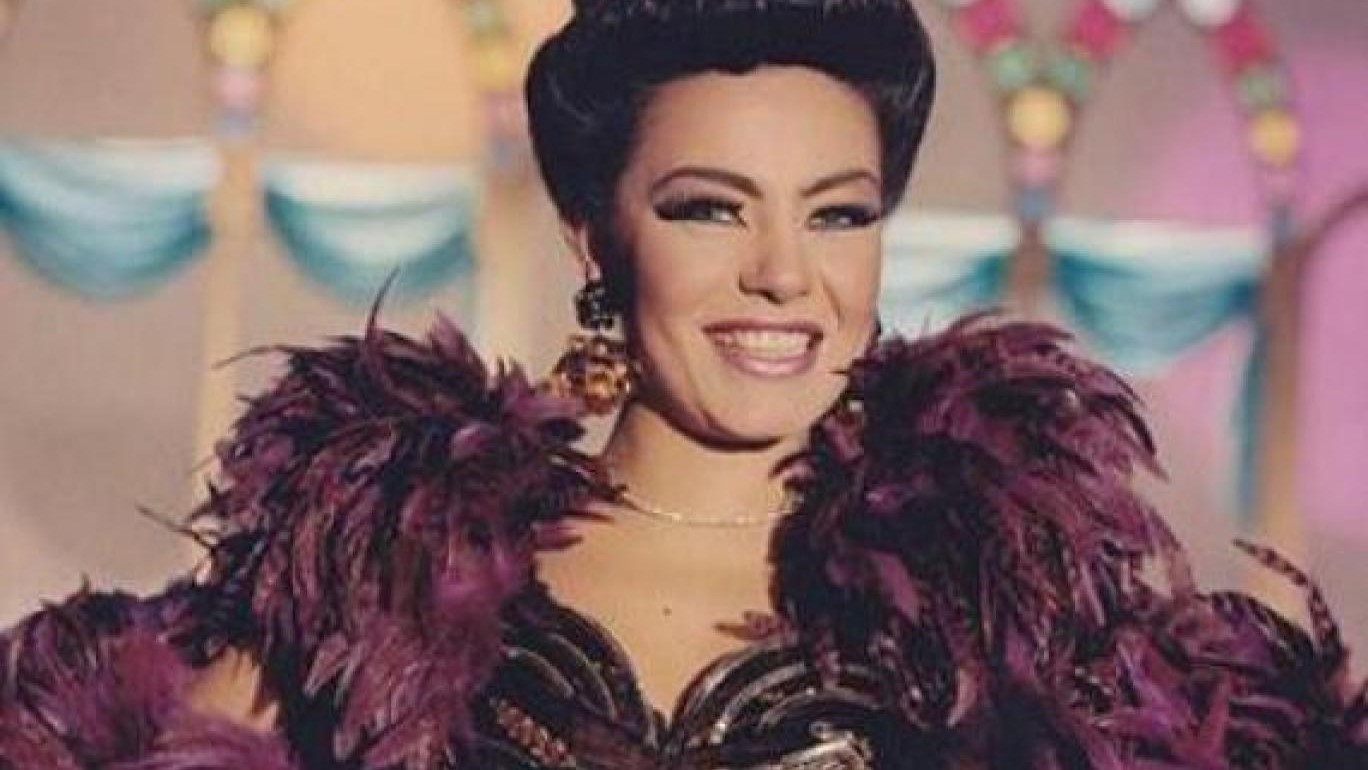

The Fawazeer, or riddles, is an inherently Ramadan invention. Broadcast for the first time in 1967, each of the 30 fawazeer episodes contained a riddle revealed at the end of the month, realised in a series of interconnected stories peppered with song and dance.

Along the years, the fawazeer grew exponentially in scope and magnitude, reaching its zenith with the genre’s two biggest stars: Nelly and Sherihan.

From 1975 till 1995 the pair created the most visually stunning musicals in Arab TV history, combining elaborate sets, garish costumes, infectious tunes, and inventively choreographed dance numbers with fantastical narratives, laced with surrealism. Imagine MGM musicals meeting Bollywood and you get an idea of the sheer magnificence of the Fawazeer.

For subsequent generations, as indicated by Dania Bdeir’s Sundance-winning short Warsha (2022), Nelly and especially Sherihan have become queer symbols for young Arabs, putting a new, unexpected spin on a genre that has stood the test of time.

Where not to start

The Gulf has had a long history of TV making, especially Kuwait, which scored its first Ramadan hit in 1970 with the comedy Aglah & Amlah.

Unlike the output of Egypt, Syria and Lebanon of late, the Gulf Ramadan series have shown little signs of progress, both narratively and aesthetically.

Catered to and largely consumed by their older local viewers, many of the region’s classic Ramadan serials - Saudi Arabia’s Ayam La Tonsa (Unforgettable Days, 1974), Kuwait’s Darb Al Zalaq (1977), Bahrain’s Sawalef Om Helal (1988) - are the stuff of nostalgia, relished largely by older viewers yet difficult to follow, or connect with, outside the Gulf.

Lebanese series remain an acquired taste: essentially, Turkish-flavoured romantic melodramas insulated from social reality and avoiding any political entanglement.

The popular and acclaimed Egyptian espionage thrillers, the most famous of which is the legendary Raafat Al Haggan (1988-1991), are undeniably compulsive but have not dated well, bogged down by a state-enforced nationalism that is prey to parody.

The historical importance of the religious series, meanwhile, cannot veil their impenetrability. Reverent to a fault and always abundant with inaccuracies, illustrious works such as the Qatar's Omar (2012), Egypt’s Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (1994) and Kuwait’s Muawiya, Hassan and Hussein (2011) are broad crash courses in Islamic history, but they don’t make for prime television.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].