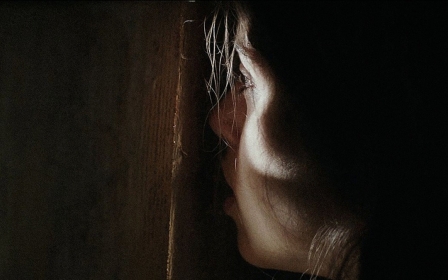

Harka: Tunisian film depicts the fire and failure of the Arab Spring

This review includes spoilers.

Set a decade after the Arab Spring, Harka (or Harqah, literally "a burning" in Arabic) depicts the desire of Ali (played by French-Tunisian star Adam Bessa) to emigrate from Tunisia to Europe.

The film's title also reflects the anger and despair that build up and consume Ali like fire, for his burning desire for a better life for himself and his sister, and the risks he takes in the process, as if playing with fire.

And then there is the burning out of the hopes and dreams of the 2011 uprisings. Finally, there is Ali's self-immolation, in a recreation of Mohamed Bouazizi's desperate act, which in 2010 triggered the uprising in Tunisia and, a month later, in Egypt.

Harka is punctuated by auditory, visual and narrative cues referring us back to the uprisings.

Bouazizi was a 26-year-old street vendor. In the wake of his fateful act, the Tunisian government rigorously enforced legislation prohibiting the unlicensed sale of gasoline. A black market of contraband fuel emerged from this prohibition, and throughout Harka law enforcement authorities take daily cuts from the gasoline racketeers.

Ali, ambitious and spiky, but with little education and no luck, becomes a bootlegger for one of the gasoline-smuggling networks.

His struggle thus becomes a microcosm of the social struggles of Tunisians in the aftermath of the hope of 2011. The filming was in fact interrupted by real-life protests responding to Kais Saied’s takeover. Footage of these demonstrations eventually became part of the film, adding a gritty, realistic and ominous effect.

Ali’s fire

Bessa shines in his portrayal of a man burning with frustration, anger, hope and despair.

The actor is matched by the film’s skilful use of its central motif. Fire is present in news reports that keep referring back to Bouazizi’s sacrifice, and in verbal cues that refer to Ali - who “wanted to burn”, referring to his wish to emigrate - and which foreshadow the film’s tragic ending.

It is also present through the overflowing of gasoline, to the extent that his sister can smell it on Ali, as if to signify that his working-class status makes him carry on his body and in his smell the material of his own burning.

We see the motif in Ali’s chain-smoking, and in the smoke that frames his body in the early scenes of the movie. It is also there in his unlit cigarette as he stands in front of the municipality building, where an employee warns him that it is forbidden to smoke - in the same place Ali will later set himself on fire.

This buildup of fire foregrounds the narrative of a society, and of a protagonist, on the brink of implosion.

Following his father’s death, Ali returns to his family home, only to discover that it's about to be seized by the bank to pay off his father’s debts.

Desperate for a quick solution, Ali ventures deeper into the gasoline black market and becomes a smuggler. This enables him to make extra money, but not enough to salvage the house.

Ali’s despair escalates. So does his anger: at the bank; at his boss, who refuses to pay him the amount they agreed on; at the police and the bribes they collect; at the authorities that close off legal opportunities and push him into illegal activity where people like him are unprotected; and at himself, for being unable to protect and provide for his sisters.

A working-class tale?

Although the film cannot be simply categorised as working-class cinema - it is, after all, a commercial film intended primarily for a comparatively bourgeois international audience and international festivals - it is not bourgeois either.

It clearly centres on the perspective of the urban, struggling poor, and it successfully imposes this viewpoint, rather than making a plea for it. The viewer is encouraged to empathise with Ali, but Ali is not rehabilitated for the bourgeois eye.

We might sympathise with his perseverance in the face of tribulations and dangers, but the film is not concerned with making Ali sympathetic

We might sympathise with his perseverance in the face of tribulations and dangers, but the film is not concerned with making Ali sympathetic. Sometimes it feels like even he cannot bear himself, or that he deals with his existence as a burden to himself and others.

The film’s narration, through the voice of Ali's younger sister Alyssa (Salima Maatoug), adds an element of mythologism to Ali’s quests. This not only positions the struggling delinquent as the (almost) mythological hero, but makes us empathise with the hero as he descends into the world of smuggling, and into failure.

The redeeming quality lies not in Ali’s own triumphs but in the sense that he is pushing himself to his limits for the sake of his sisters. This counters the ideology of individualism and individual success, promoted by Hollywood and embraced by mainstream audiences.

The final futility

Harka perhaps needed a few more details to drive the plot further. The protagonist’s eruption into self-immolating anger, though understandable and foreshadowed through the Bouazizi references, felt rushed, contained in a few minutes towards the end of the film.

Or perhaps this is the point: that Ali’s fire can be sensed as it built up, but only witnessed in its moment of eruption.

We may also wonder why Ali killed himself at a time when he seemed to have found a solution, albeit temporary, to his sisters' problems - the family had found a temporary abode and Ali was able to give his sisters the cash he was initially trying to save to rescue the house.

But perhaps Ali, suicidal throughout the film, chose to depart at a moment when his sisters had the means to manage until they'd figured out how to survive without him.

A premeditated decision to spare himself, and others, of his existence, or a mere eruption of madness? The film leaves the question unanswered, and with it the issue of whether Ali’s sacrifice was an act of individual desperation or political protest.

Self-immolation, nevertheless, blurs the lines between the personal and the political. The body that is socio-politically controlled and starved is the body that erupts in protest. Regardless of Ali’s intentions, there is no line separating the social and individual bodies.

But here lies the main tragedy of the film. Whereas the act by Bouazizi inspired an uprising not only in Tunisia but also in Egypt and across the Arab world, Ali’s sacrifice inspires nothing. In the final scene, people walk past him indifferently as his body burns.

Ali may have reenacted the scene that sparked the 2010-2011 protests, and may have been inspired by the same anger and frustrations that drove Bouazizi, but no revolution is in sight.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

* If you need support in the UK, then the Samaritans can be contacted at [email protected] or on 116 123. For the US, please try the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 1-800-273-8255. For other countries, please see befrienders.org.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].