Sudan faces dire food and medicine shortages as fighting wreaks havoc

Sudanese caught between the country’s warring factions are struggling to find affordable food and other vital supplies, as prices soar, shops are looted and key infrastructure is destroyed in the fighting.

After almost two weeks of conflict between the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary, supply chain problems have led to a situation where many Sudanese face either empty shelves or vastly increased prices.

While there is still food and water to be found in some shops and supermarkets in Khartoum, customers are complaining of exorbitant prices, with the owner of one supermarket telling Middle East Eye that the cost of bringing in supplies had been hit by a sharp increase in the price of fuel and transport. This explained the rise in prices, he said.

In Wad Madani, a city south of Khartoum in east-central Sudan, prices at grocery stores have soared by 40-100 percent and basic items like bottled water are now being sold at twice their usual price, sources on the ground told MEE. People are filling barrels with water wherever they can find it.

As the price of bus tickets to reach neighbouring Egypt has reached $400 per person or more, the cost of housing in Sudan has also soared, with accommodation in a one-bedroom apartment costing up to $100 per night. In Jazira state, which has seen comparatively little fighting, studio apartments are being rented out for $50 per night.

Fuel prices have also surged, the Norwegian Refugee Council told Middle East Eye, and now stand at $670 per gallon on the black market, while previously they were $4.20 at petrol stations. Internet services are at two percent of their previous capacity, according to Africa Confidential.

“For most Sudanese people, if they don’t go to work in the morning, they cannot feed their families. They can’t stop even for one night,” Moneim Adam, Sudanese director of the Access to Justice programme, told Middle East Eye.

A group of charities and aid groups, including Unicef and Save the Children, has warned of the grave peril faced by children in Sudan if ceasefires continue to be ignored by both sides.

“Without peace, delivering food assistance and nutrition support to extremely vulnerable girls and boys and their communities becomes much more difficult,” said Emmanuel Isch, Sudan director at the charity World Vision.

Widespread poverty

In February, before the fighting began, the UN reported that 11.7 million people in Sudan, which has a population of 45 million, were acutely food insecure. While the UN said last year that nearly half of Sudan was living below the poverty line, the real figure is reportedly as high as 80 percent.

So far, more than 500 people have been killed since fighting broke out on 15 April.

“Right now the situation of food and filtered water is a huge problem. At some point, if people don’t die from the bombing and the bullets, they will die from hunger if this situation doesn’t get fixed,” Hind Fadul, a Khartoum resident seeking to leave Sudan through the eastern border with Ethiopia, told MEE.

Sudan, a big wheat importer, had also been suffering as a result of disrupted supply chains and increased prices brought about by the Russian war in Ukraine.

Sudanese farmers have for many years had to battle climate change and the hard economic conditions of their work, with many moving to the cities or abroad as a result.

Adam said that his brother, who runs a farm in northern Sudan, produced less than 40 percent of the estate’s usual supply last year because of water shortages cause by drought and the price of gas imports. The farm, partially owned by the state, had not been supplied with enough fuel by the government.

A number of local initiatives have sprung up in the wake of the fighting. The Khartoum City Food Bank, which is made up of young people from different parts of the capital, is “seeking to provide food for families in the neighbourhoods affected by the war between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces”.

Makram Waleed, a 25-year-old doctor, has built a 1,200-person strong WhatsApp community spread across Khartoum and its twin city Omdurman’s different districts, with people sharing information about the supply of basic produce.

Waleed told Arab News that the biggest requirement for most people was drinking water, but that there were also a lot of requests for medicine, particularly for diabetes and blood pressure.

The Resistance Committees, activist networks that have been at the forefront of Sudan’s pro-democracy movement, have shown particular bravery, leading efforts to distribute food and water to those that need it in the most dangerous areas.

Tagreed Abdin, an architect and mother in Khartoum, told MEE that because she is diabetic and her husband and mother have hypertension, she needs access to regular supplies of medicine. She went out on Thursday morning and could find only one pharmacy that was open.

It had no hypertension medicine and when she asked what she should do, the pharmacist suggested hibiscus tea. Abdin said she had a stock of insulin and that her husband had enough supplies for a while, but that her mother might run out.

Destroyed factories

The supply of necessities has also been affected by the levelling of key infrastructure by both warring parties.

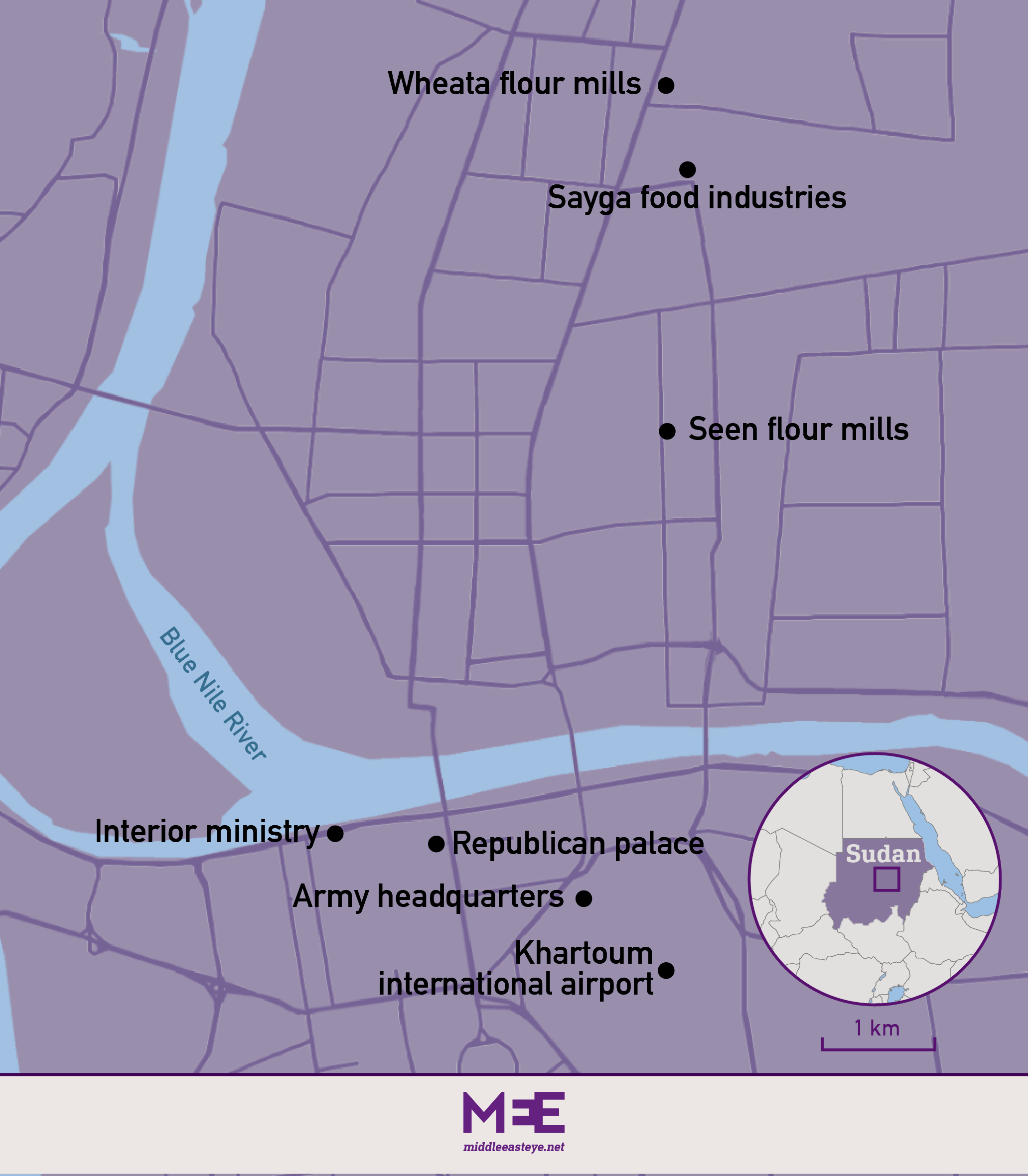

Middle East Eye has verified footage showing the destruction on Sunday of the Sayga Food Industries factory in Khartoum. One of Sudan’s largest bread and flour makers and wheat importers, the factory was shelled by both the army and the RSF.

The building burned over two days and is now an empty ruin, with soot covering its remaining walls, eyewitnesses said. Its contents were initially looted by criminal gangs, before desperate ordinary residents arrived, leaving with sacks of flour on their shoulders or using vehicles and a donkey cart to carry out dozens of grain sacks, bags of sugar and gas canisters.

Sayga is located in the Khartoum North light industrial area, which also contains suppliers and producers of pharmaceuticals, electronics, air conditioning generators, wood and cars. Residents in the neighbourhood have for years been suffering from air and water pollution caused by factories getting rid of toxic chemicals and waste.

On Sunday, deadly clashes between the army, loyal to General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the RSF, whose chief is General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemeti, created confusion in the area, leading to the targeting of businesses that were then looted.

Eyewitnesses in Khartoum and a series of videos seen by MEE show RSF fighters looting banks, shops, malls and markets.

'Armed men are entering civilian houses to take cover, forcing civilians to leave their houses. They have turned our neighbourhood into a war zone'

- Hamzan Fakri, resident Abu Halima

On Thursday, sources in Khartoum told MEE that the RSF was still the greater presence on the streets of Khartoum and Omdurman, while the army still dominates the air. The RSF is known to have burgled properties, and sources on the ground said its fighters are also trying to avoid air strikes by moving into residential buildings.

Sayga is owned by Osama Daoud Abdellatiff, a Sudanese business tycoon who also owns DAL Group, which operates wheat mills and works in mining, healthcare, energy and food and beverages.

Under the three-decade-long rule of former autocrat Omar al-Bashir, food production - like much else - was tied into the military-industrial complex, with business owners and producers connected to the state and the army.

In 2015, the Sayga factory employed around 8,000 workers and produced 5,500 tonnes of flour daily. Along with Wheata Flour Mills and Seen Flour Mills, which are both also based in Khartoum North, it is considered one of the most significant bread and flour producers in the country.

Hamza al-Fakri, a resident of Abu Halima, north of Khartoum, told MEE about the fighting he has witnessed around him.

“Armed men are entering civilian houses to take cover, forcing civilians to leave their houses. They have turned our neighbourhood into a war zone,” Fakri said.

“Many banks have been robbed. Gold shops, factories, pharmacies, supermarkets, and all types of shops are being robbed. The biggest flour factory in Sudan was hit and set on fire for two days in a row. How will we have bread?”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].