I woke to the sounds of war in Sudan. I’ve been running ever since

The sound of bombing woke me.

For months, I had been covering the growing tensions between General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the Sudanese military, and General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the leader of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

The worst-case scenario always loomed large, and here it was: RSF fighters in the streets, warplanes in the sky and gunfire rattling through Khartoum.

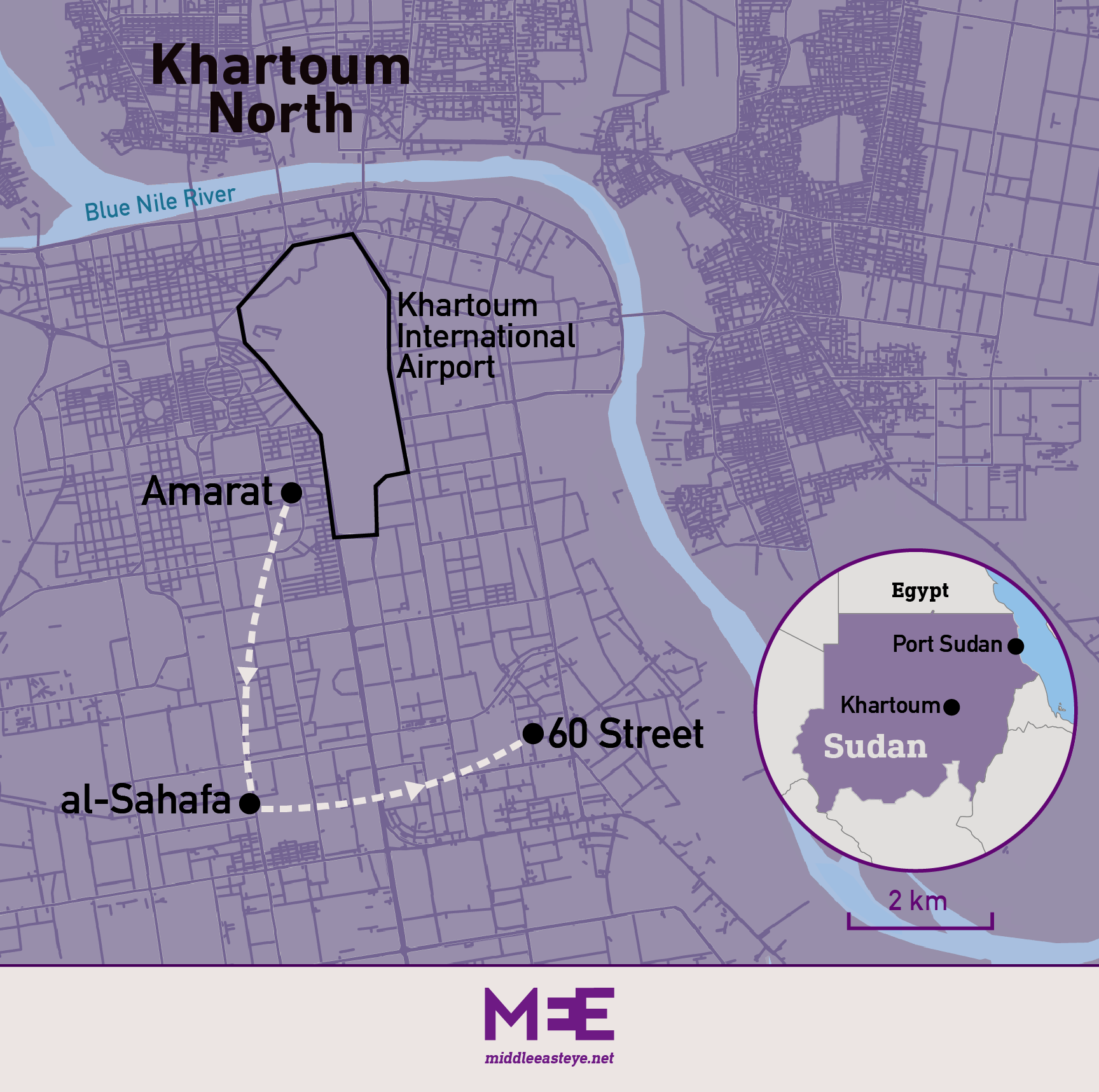

I live in Amarat, a quiet yet central neighbourhood in Sudan’s capital, with my wife and two children, aged 11 and seven. The area is near Africa Street, where the international airport is, and we are not far from the army headquarters and other government buildings. Once the location seemed ideal. Now it was deadly.

On that Saturday morning, 15 April, we could see smoke rising from the airport from our sixth-floor apartment. Below were RSF fighters storming key buildings. Two planes were engulfed in flames on the runway: one was a Saudi passenger plane; the other belonged to the United Nations.

For the next three days, we were trapped in our building as the fighting raged nearby. We could hear the shelling, the air strikes and the gunfire. The sound of anti-aircraft guns, which the RSF was using to target enemies above and below, constantly rang out. I saw a bomb strike a house two down from the Canadian ambassador’s residence.

After the first day of clashes our electricity was cut. On Monday morning, Amarat began to be hit. We heard RSF fighters were moving into buildings in our neighbourhood. I don’t know whether they were taking shelter or looking for loot, but some sources have told me tall buildings have been used as snipers’ nests.

Eid in war

The conflict was closing in. The situation was serious. We got together with our neighbours - two other families, with children and adults of all ages - to talk about what to do. We decided to leave.

Again, the bombing got heavier and we all moved down into the basement. The air down there was close. We had just one light that worked for an hour or two a day. We needed to be ready to leave at any moment, so collected the essentials - just our phones, laptops and some money. My daughters carried their tablets, so they could watch their beloved YouTube.

In many ways, this conflict breaking out a few days before Eid al-Fitr, a time of celebration, was a curse. But actually, it was one of our few pieces of good luck. Because we expected shops to be closed for Eid, we had already stocked up on food and drinks. In that basement we found some small comfort in the traditional Sudanese food we’d prepared for the holiday.

Every time there was an air strike, the building shook. It was dark. The children were terrified. But around lunchtime on 18 April things seemed a bit calmer. It was time to escape.

Together with our neighbours, we travelled in a small convoy of three vehicles through Khartoum’s battered neighbourhoods. The Resistance Committees, a pro-democracy activist network, had been moving heaven and earth to help get food and other supplies to Sudanese trapped in the fighting. They have also been helping find safe routes to flee.

I spoke to our local Resistance Committee, which told me the best route to take between our building in Amarat and al-Sahafa, a suburb of Khartoum where my wife’s extended family live.

We set out. The streets were empty. We saw incinerated vehicles along the way: both civilian and RSF. It was terrifying on the roads. There was an eeriness in the emptiness. You could expect anything at any moment. We hid our phones in case we were stopped by fighters and they were examined. I gave mine to my wife because in general, women were not being checked.

We passed a Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) checkpoint, where the eyes of ten soldiers and an officer bore down on us, terrifying my wife and children. As we approached, I felt my anger growing, but I managed to control myself. Seeing we were a group of families, they let us through without even asking for ID.

Usually, it’s pretty easy to tell the difference between the army and RSF. Army uniforms are darker, and the features of the fighters are often different.

Despite being seen as representative of the old regime of Omar al-Bashir, people in Khartoum generally feel more comfortable dealing with the army than the RSF. Rightly or wrongly, the armed forces are still seen as a national army.

The RSF, meanwhile, is a paramilitary force that grew out of the Janjaweed - fearsome militias mostly made up of fighters from Darfur in the far west and beyond. The memory of the RSF gunning down pro-democracy protesters in a June 2019 massacre in Khartoum has not disappeared, and their fighters are often hostile to the capital’s residents.

'Why are you leaving your city?'

The drive to al-Sahafa was short but it was fraught. At last, we were safe, or so we thought.

Our first night in our new home, the electricity was cut. Two days in, the sounds of battles grew closer. On the morning of 21 April, heavy fighting reached al-Sahafa. We heard the army had attacked an RSF base near the house we were staying. Someone on the street told me it had been attacked from the air - possibly using drones.

The clashes around us were getting heavier and heavier. It was worse than what we had experienced at home, lasting from dawn to dusk. Again, we had to leave, and I worked out a route to a place in the 60 Street neighbourhood that some journalists told me was safe and had electricity generators.

It was very dark on the road. I hadn’t been able to find Resistance Committee members to check the route with. We hit three different RSF checkpoints. The first two, we passed safely. The fighters were worried and tense. They were visibly uncomfortable and on edge.

At the third, the younger soldiers tried to snatch our phones before their officer intervened.

One of them looked at us and said: “You guys, why are you leaving your city?” We could see what he was implying. I’m not from Khartoum. I come from Port Sudan in the east of the country. My family are not part of any ruling elite.

But I remembered a speech that Hemeti, as the RSF leader Dagalo is commonly known, once gave, when he told the people of the capital not to be proud of their high buildings. One day, Hemeti warned, if they were not careful, those buildings could fall like a house of cards.

This fighter was telling us we were privileged. Now our city was living through terrible violence endured by many other places in the country, like Darfur. Now we knew what it was like to flee our homes.

We were lucky to escape the RSF checkpoints with all our possessions. From the moment hostilities broke out, the paramilitary fighters have been seen looting shops, homes and businesses. A moment’s hesitation when RSF fighters demand your belongings can prompt them to shoot you on the spot.

My colleagues were right. The situation in 60 Street was calmer. It had not been easy to find food in Khartoum, but a supermarket there still had stock, and together with my friend we cooked some spicey beef that we ate with bread. We may have drunk a little araq with it. It was a moment of relief.

The army and the RSF made sure westerners or people from the Gulf were safe. They were happy to kill us instead

But it was that weekend that I heard foreign diplomats were being evacuated from Sudan. This was one of the two worst moments I have experienced since the fighting began. Both the army and the RSF allowed the evacuation of foreigners while they continued to fight in the residential areas of Khartoum. They made sure westerners or people from the Gulf were safe. They were happy to kill us instead.

By that time, it was clear this war would not end anytime soon. Foreign powers would declare ceasefires, and on the ground the bullets and the bombs ignored them. I realised it was time to get my family out of Sudan.

Bus tickets to Egypt used to cost $60. Now to get my wife and daughters there it was $400 each. I had no other choice. They got on a bus with 24 other members of our family and headed north. A week later, they have only just managed to cross the border.

Not long after they left, the war found 60 Street as well, and I decided to head to Port Sudan, my hometown, the city I grew up in.

The vultures are circling

I’m here on the Red Sea coast now. The situation is both chaotic and stable. But here I found the second-worst moment of this conflict: the arrival of aid agencies.

I’ve seen this before. When the international aid agencies come, the countries that depend on them are gone with the wind. This should never have happened to Sudan.

More than anything, I feel angry. More than feeling sad or frustrated, I feel angry. I am angry with the warring forces. I am angry with the diplomats who have left us here. This is my homeland. This is where I grew up. I know thousands of people here. My friends, my family, my people.

I know Port Sudan and I know it will be trapped in the middle of a terrible international competition. I can see the warships from China, the United States and France off the coast. I don’t think this part of the country will be owned by the Sudanese anymore. The vultures are circling. There are crows in the air; they mark the coming of something and it is not good.

Prices are going up here already. Local people don’t have much but they are relatively happy. It is a stable situation in Port Sudan. But they won’t be able to afford to live here for long. Even those people bringing relief will make this city too expensive. Port Sudan will not be able to cope, it does not have the infrastructure.

Sometimes, as a journalist, you feel like you know too much. Sometimes it’s good to know things. Sometimes it just leaves you with a lot of bad and bitter feelings and you don’t know what to do with them. After all, you are just a journalist, you aren’t a general or a president or a warlord or an ambassador.

This week, I will go to the Egyptian consulate in Port Sudan. I am not sure when or where I will next see my family, though I think - and hope - that it will be in Cairo, and before too long. For now, I am in my homeland. But my homeland has become a hell.

Photo: A man looks at the damage inside a house during clashes between the Rapid Support Forces and the army in Khartoum, 17 April (Reuters)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].