Turkey elections: After two decades of AKP rule, a showdown looms

Turkish citizens are getting ready to vote in presidential and parliamentary elections on 14 May for what may be the nation’s most critical, and certainly one of the most competitive, ballots of the last two decades. Can the Nation Alliance, led by the Republican People’s Party (CHP), defeat the People's Alliance, led by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP)?

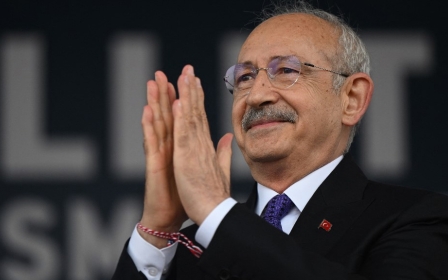

Voters will choose the president in a two-round election from among four candidates. They will also elect the parliament. Yet, while CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu is several points ahead of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in recent polls, the numbers are far from conclusive, with many voters still undecided.

Nonetheless, it is quite clear that in its 21 years of rule, the AKP has never come this close to losing an election.

Turkey’s transition to a super-presidential system in 2018 is closely correlated with an increased chance of incumbents losing power. The switch created two substantial transformations in Turkish politics.

The first was institutional, giving party politics and the electoral system a majoritarian logic that encouraged coalition-building among parties. In addition, Turkish electoral law was modified to make it possible for political parties to participate in elections by formally establishing coalitions. Coalitions also enabled smaller political parties to get around Turkey’s high electoral threshold.

While these changes were designed to strengthen Erdogan’s rule and the executive branch, they came with significant unintended consequences. The transition to majoritarian politics, along with modifications to the electoral system, spurred opposing players from across the political spectrum to unite. By enhancing the possibilities for smaller parties to influence results, the new system also fostered the emergence and persistence of parties that represent diverse cleavages in society.

These parties were then able to be accommodated within the opposition alliance, significantly raising the credibility of the assertion that it encompassed all segments of Turkish society.

Inverted populism

These institutional dynamics shaped the competition field both during the 2018 general elections and 2019 local elections. The opposition used the authoritarianism-versus-democracy cleavage as a unifying factor in both elections to bring ideologically disparate political groups together. In doing so, the opposition was able to largely overcome the limits of the conservative-secular cleavage that has dominated Turkey for the past two decades under AKP leadership.

During the 2019 local elections, the Nation Alliance used what could be labelled as the strategy of inverted populism. This new strategy, which has continued during the 2023 election campaign, rested on three pillars: avoiding direct confrontation with Erdogan and the popular values he represents; redefining “the people” by including all segments of Turkish society; and promising financial redistribution to disadvantaged groups. Issues such as foreign policy, in which the incumbents have a clear strategic advantage, have been sidelined.

The opposition was able to largely overcome the limits of the conservative-secular cleavage that has dominated Turkey for the past two decades

Through this strategy, the Nation Alliance won major victories in Turkey’s metropolitan cities and seriously challenged the incumbent political bloc in the 2019 municipal elections. Particularly significant was the victory in Istanbul, where Ekrem Imamoglu’s election as mayor ended the hegemony of the AKP in the economic and cultural capital of Turkey.

The general public’s trust in the opposition’s capacity to rule, as well as the opposition’s self-confidence, were both significantly boosted with these municipal victories. Most significantly, they allowed the opposition to break through the psychological barrier that portrayed the AKP as an unbeatable opponent.

The second change brought about by Turkey’s 2018 transition to a super-presidential system relates to the de-institutionalisation and de-democratisation of Turkish politics. The new system, which granted the executive superpowers and lacked any kind of checks and balances, quickly destroyed Turkey’s functioning institutions. The system turned out to be not only a de-democratising path for Turkey, but an obstacle to addressing growing economic challenges.

In the past, the AKP’s strong economic performance was a key factor in its continued electoral success and the effective use of formal and informal redistributive mechanisms. This was critical to the AKP’s ability to forge a cross-class electoral coalition. Today, the decline in economic growth rates, combined with sharply rising inflation, have made it more likely for AKP supporters to defect based on economic and democratic dissatisfaction - albeit slowly.

Shifting support

Although the AKP is Turkey’s largest party, the continued disintegration of its electoral base has made it more challenging to gain the necessary 50 percent + 1 of the vote for the presidency. The AKP’s percentage of the total vote in 2018 general elections was 43 percent, while that of its key coalition ally, the National Movement Party (MHP), was 11 percent. Currently, according to a number of polls, the MHP’s support is about 7 percent and the AKP’s 35 percent.

Yet, anti-Erdogan sentiments among the electorate do not necessarily translate into direct support for the Nation Alliance, which needs the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP)’s support to guarantee a parliamentary majority. The HDP-led Labour and Freedom Alliance recently declared its support for Kilicdaroglu, making him the clear frontrunner.

This significant electoral backing, however, requires the Nation Alliance to strike a tough balance, as this collaboration risks alienating nationalist voters. The fact that the nationalist-leaning Good Party is in the alliance is not enough to satisfy voters who want more hawkish policies on topics such as immigration and the Kurdish issue.

Knowing this, the incumbent government is using the nationalist card and anti-HDP sentiments to sway undecided voters away from the opposition, and increase its support among those who value “state security”. The government’s narrative centres on framing the opposition as an alliance of “traitors and terrorists”, with the pro-Kurdish HDP having a hidden seat at the table. The Nation Alliance is commonly known as the Table of Six; Erdogan has renamed it the Table of Seven.

The other two candidates running for president, Muharrem Ince and Sinan Ogan, make it even more unlikely for Erdogan or Kilicdaroglu to win a majority in the first round of voting.

Meanwhile, Turkish society remains deeply divided, even when it comes to an event as devastating as the recent earthquake that killed more than 55,000 people. A recent poll found that less than 40 percent of respondents were satisfied with how the government handled the earthquake - but there were significant divisions along partisan lines, with more than 90 percent of AKP voters giving a favourable rating and more than 95 percent of CHP voters giving a negative rating.

These numbers show why Turkey’s next election is being viewed as a battleground. Many participants have made up their minds and will not change their thinking, no matter what happens. But the choices of those who have grown discontented with both the incumbents and the opposition will have an enormous effect on the outcome.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].