How the world grew to understand the Nakba

On 22 November 2022, the United Nations General Assembly asked the Division of the Secretariat for Palestinian Human Rights to "dedicate the activities of 2023 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Nakba".

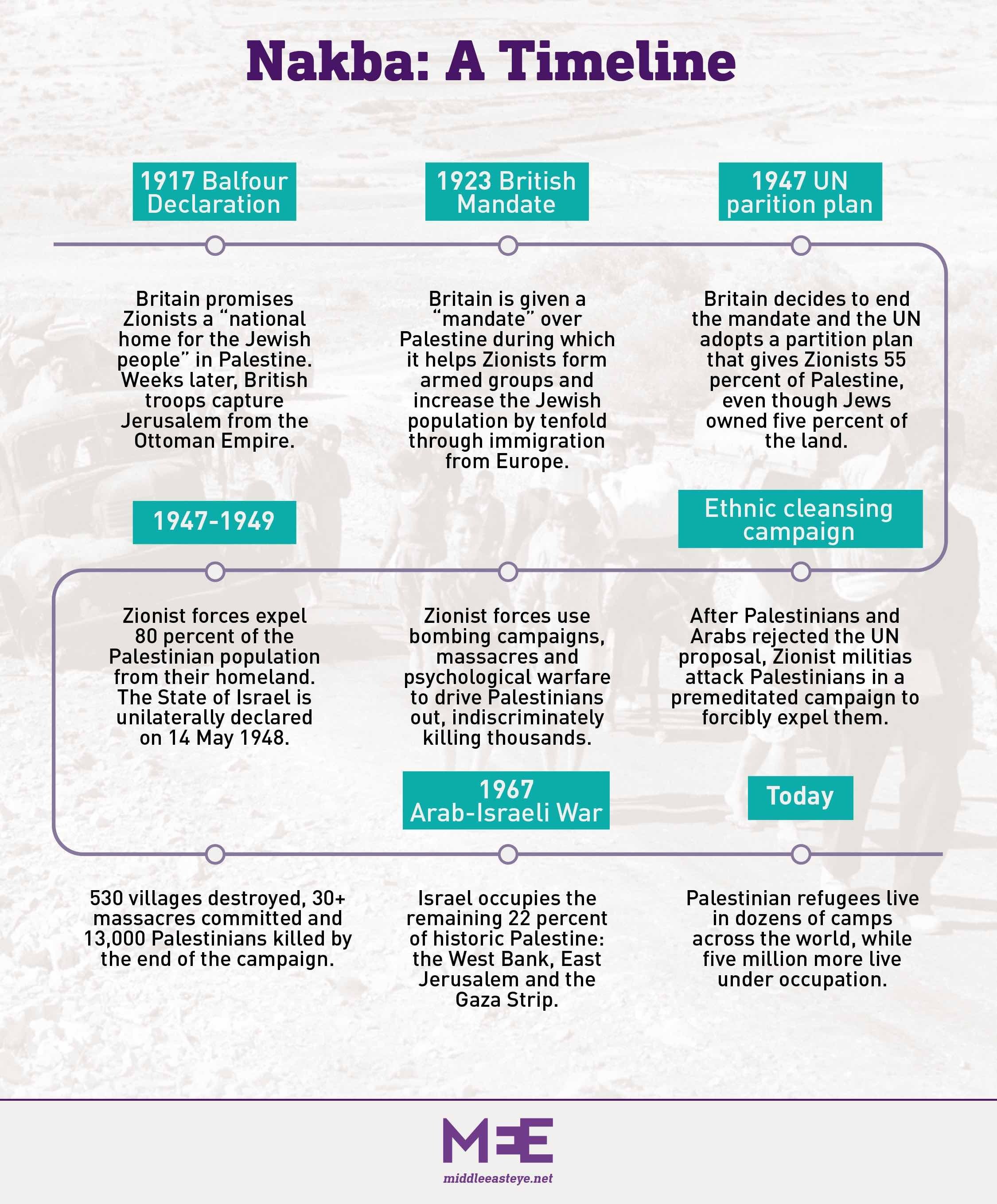

The Palestinian population suffered the Nakba - the Arabic word for "catastrophe" - when their society was destroyed with the creation of Israel in 1948. The UN official request recognises its role in the forced expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians from their lands, through resolution 181, the "Partition Plan", which proposed dividing the territory of Palestine into two states, one Arab and one Jewish.

At that time, the world celebrated the creation of the Jewish state as a response to the genocide perpetrated against the Jews by Nazism. Very few outside the Arab world paid attention to the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of people from their homes. It continued to such an extent that it took decades for the term "Nakba" to gain traction as a political concept identifying the catastrophe suffered by the Palestinians.

Despite its appearance in a 1948 book by Syrian intellectual Constantin Zureik, popular use of the word "Nakba" was short-lived until the end of the 1980s. Though it is widely invoked today, it was not part of the Palestinian political narrative for almost 40 years. This does not mean that the catastrophe was unknown, quite the contrary; it was often referenced as part of the collective memory.

For this reason, it is interesting to examine why the word "Nakba" was hardly used for decades only to later reemerge as a political concept in itself, with the original Arabic being used without translation in all languages, including Hebrew.

The importance of words

In any political issue, let alone in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, words play an important role in shaping public discourse. The inclusion and exclusion of words, a deliberate choice and not left to chance, is part of a dialectical game that seeks to impose a narrative whether locally or in the mass media.

The spread of the term 'Nakba' has debunked Israel's version of history, which erases the systematic destruction of the pre-existing Palestinian society

The use, repetition, and internationalisation of a concept can have a positive or negative connotation. Perhaps the best-known case is how the term "apartheid" - in its own language of Afrikaans - became understood globally as a system of exclusion and segregation, and not only with respect to the Black population of South Africa.

The 1987 Palestinian uprising allowed an Arabic word, for the first time in the history of the conflict, to penetrate the international media, and even the discourse within Israel, without pejorative connotation. The Intifada, which literally means "shake" or to shake something (annoying) off one's shoulders, later became identified - and, to a certain extent, legitimised - as the Palestinians' peaceful fight against the powerful Israeli army.

Other words that gained international recognition include the Arabic word fedayeen (fighters), though it was initially only claimed by those who supported the struggle of the Palestinian resistance. The Naksa, which means setback or defeat, became widely used in reference to the June 1967 war when the Israeli army occupied the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Gaza Strip, the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, and the Syrian Golan Heights. The expression, however, does not hold the same weight outside of the Arab world.

Until 1987, most western media outlets were influenced by the Israeli version of events. An example of this is the 1973 Arab-Israeli war that became known in the West as the "Yom Kippur War" when Arabs generally refer to it as the "October War" or the "Ramadan War".

For decades, the Nakba that Palestinians suffered in 1948 was absent from any narrative that embraced Israel's version of history, which celebrates its statehood and "independence" while erasing the systematic destruction of the pre-existing Palestinian society.

However, oral transmission, poetry, stories about the lost land, research carried out by Palestinian intellectuals, and the spread of the term Nakba to denote the catastrophe suffered by the Palestinian people in 1948 have managed to debunk the version disseminated by Israel.

The debate over 1948

The expulsion of the majority of Palestinians from their homeland is undeniable from a historical point of view and has been thoroughly documented. One example of such evidence is a letter from Israeli Prime Minister David Ben Gurion to his son, in which he expressed his belief that the Palestinians would not leave voluntarily. He bluntly writes: "We must expel the Arabs and take their places."

Similarly, Yosef Weitz, the director of land and afforestation at the Jewish National Fund (JNF), wrote in his diary: "It must be clear that there is no space for both peoples in this country." Of course, the Palestinians were not prepared to abandon their land, much less face expulsion en masse. Most thought they would return and even kept the keys to their homes, but were prohibited from ever doing so.

The expulsion began before the end of the British Mandate, but in June 1948 the destruction of Arab towns was implemented as official policy. In Tel Aviv, Weitz met with Ben Gurion who had become prime minister, to present him with a three-page memorandum titled "Retroactive Transfer: A Scheme for the Solution of the Arab Question in the State of Israel". There it was called to prevent the return of Arabs to their homes by destroying their villages during military operations and to settle Jews in Arab towns and villages.

The evidence provided by the Zionist movement's own archives demonstrates a similar line of thought among the different Jewish leaders who considered the dispossession and exile of the Palestinians necessary. Therefore, the damage done to the Palestinians in 1948 was not accidental or an unintended consequence of war.

What is new is that in recent years, as a result of several historiographical studies and its use in the media, the Nakba concept reappeared and is now part of the mainstream narrative.

Studies on the Palestinian Nakba have multiplied since the 1980s and focused on oral accounts that debunked the Israeli myth of the "flight of the Arabs". This is also due to the declassification of files and documents from the 1948 war by the UK and Israel, which favoured the academic debate regarding what happened in Palestine.

Rosemary Esber's 2004 work, Rewriting The History of 1948: The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Question Revisited, described the situation: "The investigations of Nazzal and Morris have been the most detailed and systematic studies that tried to explain the causes of the Palestinian exodus of 1948...but the results of the evaluation of the documentation, expanded by the oral histories of those who lived through the expulsion, show that 94 percent of the Palestinian population was displaced...expelled by violence and direct attack by Zionist forces".

After the creation of the State of Israel, the figure of the Palestinian refugee was consolidated as time passed and the Palestinians were not allowed to return to their lands to recover their properties. The first tendency of many families was to remain in nearby places awaiting the moment to return, but after decades of forced exile, the majority dispersed to numerous countries and a minority managed to stay within the limits of the new State of Israel.

However, family ties and friendship between the inhabitants of the same villages or camps became fundamental and enabled the necessary cohesion to maintain identity and strengthen the Palestinian collective memory in which the experience and memory of the Nakba as a historical story-identity acquired a relevant role. Consequently, the Nakba evolved from being an experiential story to forming part of the political discourse of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO). This was the case despite the Israeli historiographic efforts to erase the record of ethnic cleansing.

Nakba as a political concept

Constantin Zureik was the first to use the concept of the "Nakba" about what happened in 1948 in his book "Ma'na al-Nakba", (The Meaning of the Disaster), published in Arabic in August 1948 and then translated into English in 1956 by Richard Bayly Winder of the Department of Oriental Languages at Princeton University in the US.

Zureik took a word applied to misfortunes or calamities to give it social content, although his book was not widely disseminated at the time outside the circle of some Arab intellectuals. It also did not become the "official version" of the Palestinian account of what happened in 1948.

Zureik's main purpose was to understand the magnitude of the catastrophe in the Arab world from a regional and geopolitical point of view. For his analysis, the "Palestinian question" was secondary, as was the population displacement that had occurred, although he did not fail to mention it.

His book is a text of critical analysis of the leaders of the Arab countries during the creation of the Jewish state. Along the same lines were other works of the time, such as those of Musa al-Alami, Muhammad Nimr al-Khatib, Muhammad Nimr al-Hawwari, or that of the Palestinian historian Arif al-Arif, who used the term in his monumental work Al-Nakba: Nakbat Bayt al-Maqdis wa-l-Firdaws al-Mafqud, 1947-1952 (The Disaster: The Jerusalem Disaster and Paradise Lost).

As Palestinian historian Adel Manna rightly points out, the first works written after 1948 were important contributions to the Arab understanding of the traumatic event and the conditions for coping with its results, but where the Palestinian question took second place.

Given the devastation the Nakba caused, the Palestinians did not, at first, write their own history. Those affected transmitted the experience of what happened from generation to generation orally without the urgent need to find an exact definition of what happened.

It is often said that history is written by those who win and, in this case, the rule is confirmed. The founders of Israel systematically denied their expulsion of the Palestinian population and western media - the most influential in the world - readily broadcast the Israeli version, claiming that the Palestinians fled on the orders of the Arab countries and that there was no expulsion of any kind. However, numerous researchers have refuted this version of the "supposed orders".

Palestinian historian Walid Kalidi, one of the founders of the Beirut-based Institute of Palestinian Studies, assures that:

“On 15 May, the Arab News Agency reports that Arab radio stations announced three statements by the high committee. The first urges the members of the Supreme Muslim Council, the officials of the Muslim courts and Waqfs, the imams and the servants of the mosques to continue their duties. The second statement requests the officials of the jail department to continue their tasks, the third requests all Arab officials to remain at their posts. Surely this is a very strange way of ordering the evacuation of the country."

The main obstacle to the creation and maintenance of the Jewish state in Palestine was - and still is several decades later - the presence of an autochthonous population that continues to be attached to its land. The denial of the Nakba is, consequently, closely related to the denial of Palestine and the Palestinians by the different Israeli governments. The effort to deny expulsion and dispossession resides in the fact that "if this is Palestine and not the land of Israel, then you are conquerors and not tillers of the land; you are invaders. If this is Palestine, then it belongs to the people who lived here before you came."

The pro-Israel propaganda paradigm was challenged by numerous Palestinian researchers. However, the rise of the New Historians marked a turning point and made it possible to question the official Israeli version, making an impact on the European and North American collective imagination. Israeli academics who gave credence to Palestinian claims of expulsion were now questioning their society and the official discourse.

Recording history

As usually happens in the face of a collective traumatic event, one must wait for a generational change to begin to reconstruct one's own history in an orderly manner. At first, the objective of some Palestinian intellectuals was to try to refute the Israeli version of events, rather than tell their own story. It is possible to think that the effect of the shock caused by the destruction of their society implied the absence of the word nakba in the media or academic discourse.

However, the catastrophe as such, even without using the word Nakba, was always present. As anthropologist Diana Allan points out:

"In the 1950s and early 1960s other, more euphemistic terms were used to describe the events of 1948, including al-ightisab (the rape), al-ahdath (the events), al-hijra (the exodus), lamma sharna wa tlana (when we blackened our faces and left). As the Palestinian society had been destroyed, Palestinian families were left to survive while waiting for the liberation of their lands with the help of the Arab countries that allowed them to return to their homes. But, that didn't happen."

Only in the 1960s did the appearance of the PLO as an organising force for the Palestinians and the production of numerous Palestinian intellectuals allow an approximation to what happened in 1948. It is interesting that at that time, when the expulsion of 1948 was mentioned, numerous Palestinian documents disseminated throughout the world used words such as massacre, occupation, and expulsion, and insisted on the dispossession of the majority of the original inhabitants of Palestine without resorting to the word Nakba.

This can be verified by reviewing documents and political statements of the main Palestinian representatives, including then PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat. Furthermore, in the first major document of PLO principles - the famous Palestinian National Charter of 1964 - the word Nakba is not mentioned even once. On 13 November 1974, Arafat appeared before the UN General Assembly. After citing different struggles of Third World peoples, Arafat goes back to the rise of the Palestinian question in the 19th century with the appearance of what he calls the Jewish invasion of 1881 and the presence of 1,250,000 Palestinians in 1947.

There he says that the Zionist movement "occupied 81 percent of the total area of Palestine, expelling one million Arabs and occupying 524 cities and towns, completely destroying 385 in the process...The root of the Palestinian question is here...It is that of a people expelled from their homeland, dispersed and living mostly in exile and in refugee camps...thousands of our people were killed in their own towns and cities, tens of thousands were forced to leave their homes and the land of their parents at gunpoint...no one who has witnessed the catastrophe will be able to forget their experience.” Arafat's speech at the United Nations is in Arabic and in the English transcription the word catastrophe appears three times.

However, the term Nakba is not used as a synonym for catastrophe because in 1974 this word as a concept had not been incorporated into political language, not even among Palestinians. If one bothers to look up the word Nakba in the Journal of Palestine Studies, the prestigious political and academic journal directed by Rashid Khalidi, you will find almost 600 articles that mention it; however, almost all are from the 1990s onwards. This means that, although the word Nakba was perhaps used in the everyday language of many families, it was not part of the political discourse.

At the International Conference on the Question of Palestine held by the United Nations in Geneva on 29 August - 7 September 1983, a group of renowned intellectuals presented what they called the "Profile of the Palestinian people". There, Edward Said, Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, Janet Abu-Lughod, Muhammad Hallaj and Elia Zureik told the story of their people:

"The current situation of the Palestinian people has its roots in a concrete historical event: the dismemberment of Palestine in May of 1948. The emergence of Israel then in a portion of Palestine, had two consequences: First, the Palestinians were expelled...Second, there was the legal and administrative incorporation of the remaining areas of Palestine by Jordan and Egypt... Both parts were occupied by Israel in 1967. Thus, the entire Mandatory Palestine area is now controlled exclusively by Israel.”

In this meeting, the dismantling of Palestinian society and the preparations for the elimination of the Palestinians are mentioned, but the word Nakba as such does not appear either. Further, in November 1988, the Palestinian National Council met and formally proclaimed the independence of Palestine. In the approved document, reference is made to the expulsions of 1948 but the word Nakba does not appear either. A month later, Arafat addressed the United Nations in Geneva to declare the independence of the State of Palestine without using the word Nakba.

Around the same time, the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) was born and published its first public charter in August 1988 without the word Nakba appearing. It took several years until word as such appeared on its official page as a section to explain what happened in 1948.

In general terms, we can affirm that the expression nakba was not used publicly and recurrently as a political concept until the 1990s.

The 'Nakba' reemerges

Numerous Palestinian historians - among them the renowned Walid Khalidi and Salman Abu Sitta - dedicated themselves to exposing the planning and expulsion of the Palestinians from their land. However, the appearance of Israel's New Historians allowed the major European and American media and intellectuals to echo the "new version" of this history.

If until then the Palestinian narrative was considered 'propaganda' in the face of the Israeli 'truth', once the New Historians disseminated their research, it could no longer be ignored

If until then the Palestinian narrative was considered "propaganda" in the face of the Israeli "truth", once the New Historians disseminated their research, it could no longer be ignored that there was another story because, within the same Israeli society, there appeared academics who questioned in a documented and forceful way the repeated Israeli narrative.

Through their texts, Simha Flapan's The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities, Benny Morris's The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949, Ilan Pappé's Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1948-1951, Baruch Kimmerling and Joel Migdal's The Palestinian People: A History and Avi Shlaim's Collusion Across the Jordan, just to name a few, questioned the Israeli version of history and recognised that the mass expulsion of the Palestinian population had taken place.

It is interesting to note that, although their texts reported what happened in the period between 1947 and 1949, they too were slow to incorporate the word nakba as a concept associated with the catastrophe of 1948.

In 1988, Benny Morris published the article "The New Historiography: Israel Confronts Its Past" in the Jewish American magazine Tikkun, where he explains the appearance of the new historians who questioned the official history.

However, when analysing the expulsion of the Palestinian population, he does not use the word nakba but "exodus". In the analytical index of the aforementioned book by Pappé, published in 1994, the word nakba does not appear, although several years later he himself became one of the most prolific authors in using it to explain the expulsion of the Palestinian population in 1948.

In her book, Co-memory and Melancholia: Israelis Memorializing the Palestinian Nakba, sociologist Ronit Lentin attempts to trace the use of the nakba concept and found that the first scholarly work in Hebrew using it was by Kimmerling in 1999.

However, Kimmerling and Migdal published their book in 2003 and used the expression Jil al-Nakba (The Generation of the Disaster) to explain the experience of exile, although without giving much importance to the nakba concept itself. Moreover, they dedicate the chapter "The Meaning of the Disaster" to describe the Palestinian expulsion process between 1947 and 1948 using the same title as Zureik's book, although they do not mention the Syrian intellectual throughout the book.

The appearance of the New Historians opened a crack in western and Israeli media coverage of Israel's hegemonic account when contrasted with documents from the Israeli military itself. The Oslo Peace Accords of 1993 reinstated the debate on what happened in 1948, since one of the demands raised by the Palestinians was the return of refugees.

The recognition of the existence of refugees implied for the agreements an acknoweldgement of their expulsion, which, in turn, became synonymous with Nakba. Although the issue of the 1948 Palestinian refugees reappeared in the negotiation process, in the Declaration of Principles of 13 September 1993, the word refugees appears only once and as one of many issues to be dealt with in the future.

Calling for a resolution to the Palestinian refugee problem allowed the exposure of what happened in 1948. By then, the Palestinian version of the expulsion had the support of the Israeli New Historians.

This also explains why various non-governmental organisations arose, alongside displaced Palestinians in Israel, and formed an action committee in March 1995 to reaffirm the right of return for all Palestinians. The Association for the Defence of the Rights of the Palestinians (ADRID) among 1948 Palestinians was born and so were the annual marches to their depopulated villages to commemorate Nakba Day.

In 1998, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the expulsion of 1948, Arafat declared 15 May as The Day of the Nakba, turning what happened in 1948 into a political concept. After his death in 2004, Mahmoud Abbas replaced him at the Palestinian National Authority and as such, on 29 November 2012, he spoke before the UN General Assembly. There, he clearly stated:

"The Palestinian people, who miraculously recovered from the ashes of the Nakba of 1948, which was intended to extinguish their being and to expel them in order to uproot and erase their presence, which was rooted in the depths of their land and depths of history. In those dark days, when hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were torn from their homes and displaced within and outside of their homeland, thrown from their beautiful, embracing, prosperous country to refugee camps in one of the most dreadful campaigns of ethnic cleansing and dispossession in modern history."

As we can see, the Nakba concept had already found its way into the Palestinian leadership's political language.

The use of the term Nakba by the Palestinians and its use in the media following the New Historians also influenced some Israeli politicians. Shlomo Ben-Ami, a former Israeli foreign minister and historian, wrote several books on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In Israel, entre la guerra y la paz, (Israel, Between war and peace) published in 1999, he provides the traditional Israeli line regarding the events of 1948. However, in his 2005 book, Scars of War, Wounds of Peace: The Israeli-Arab Tragedy, Ben-Ami recognises the "atrocities and massacres committed against the civilian population” and uses the term "Naqba" to explain the dissolution of the Palestinian Arab community in 1948.

Memory as resistance

While Israel celebrates its Independence Day each year on 15 May, Palestinians and their supporters around the world commemorate the Nakba as the massacre of Palestinians and expulsion from their lands. Yet, for more than 75 years, the narrative of Palestinian dispossession has been a field of struggle against Israeli denialism.

Since the First Intifada, some Israeli academics began to deconstruct that official history and the paradigm began to crack. In the words of the Israeli Eitan Bronstein of the Zochrot Association: "If the Nakba never happened, it is impossible that today millions of Palestinians are refugees demanding the restitution of their rights".

Political attempts to commemorate the Nakba as a singular, bygone event, rather than an ongoing process, are doomed to fail. Memory has always been fundamental to Palestinian resistance. By insisting on identifying their country, cities, and towns by their original names, generations of Palestinians have strengthened a collective memory that Israel has endeavoured to erase.

The concept of Nakba has not found translations into other languages that manage to cover all the nuances of its meaning in the original Arabic. The Nakba is not only related to a purely epistemological aspect, but also encompasses cultural, ideological, political, communicational and even media aspects. Accordingly, the Nakba not only refers to aspects of the destruction of much of Palestine and the expulsion of its original inhabitants who, although they resisted, failed to prevent the mass expulsion and massacres in 1948.

The appearance of the word Nakba in mainstream media outlets can be considered a political and public relations achievement for the Palestinians. Now, when the anniversary of the founding of the State of Israel is commemorated, the mass media are forced to explain the catastrophe suffered by the Palestinians using the word Nakba in Arabic.

It is no longer just a catastrophe like so many others, it is the Nakba, with all the weight that using the word in Arabic implies. The domain of discourse and media spaces are fundamental in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. According to Palestinian researcher Amjad Alqasis, it is also imperative for Palestinians to create their own discourse, which could be achieved by introducing and establishing their own language and terminology.

Israel has dominated those language spaces internationally for decades. However, the Nakba is a process that continues and provokes various resistance practices that have prompted the Israeli government to even legislate on it, prohibiting the commemoration of this date.

Employing certain language and terms like Nakba and Intifada reflects important changes - ranging from a claiming of a people's identity and agency to narrative shifting in the media - which has a profound impact on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

The big change compared to previous years is that the Palestinians no longer appear as mere "refugees" who were allegedly "ordered" to flee Palestine by Arab governments, as the Israeli version stated. Rather, it is now an established fact that they are victims of expulsion from their territory.

The legitimacy obtained in the media sphere is also transferred to the political sphere and gives greater support to the fight for their rights, be they for the establishment of an independent state or to reinforce the demand for the return to the land of the refugees expelled in 1948.

And the word Nakba, which took a leap from the personal to the political, was the key to this transformation.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].