Egyptian hunger striker's health declining as he protests South Korea deportation

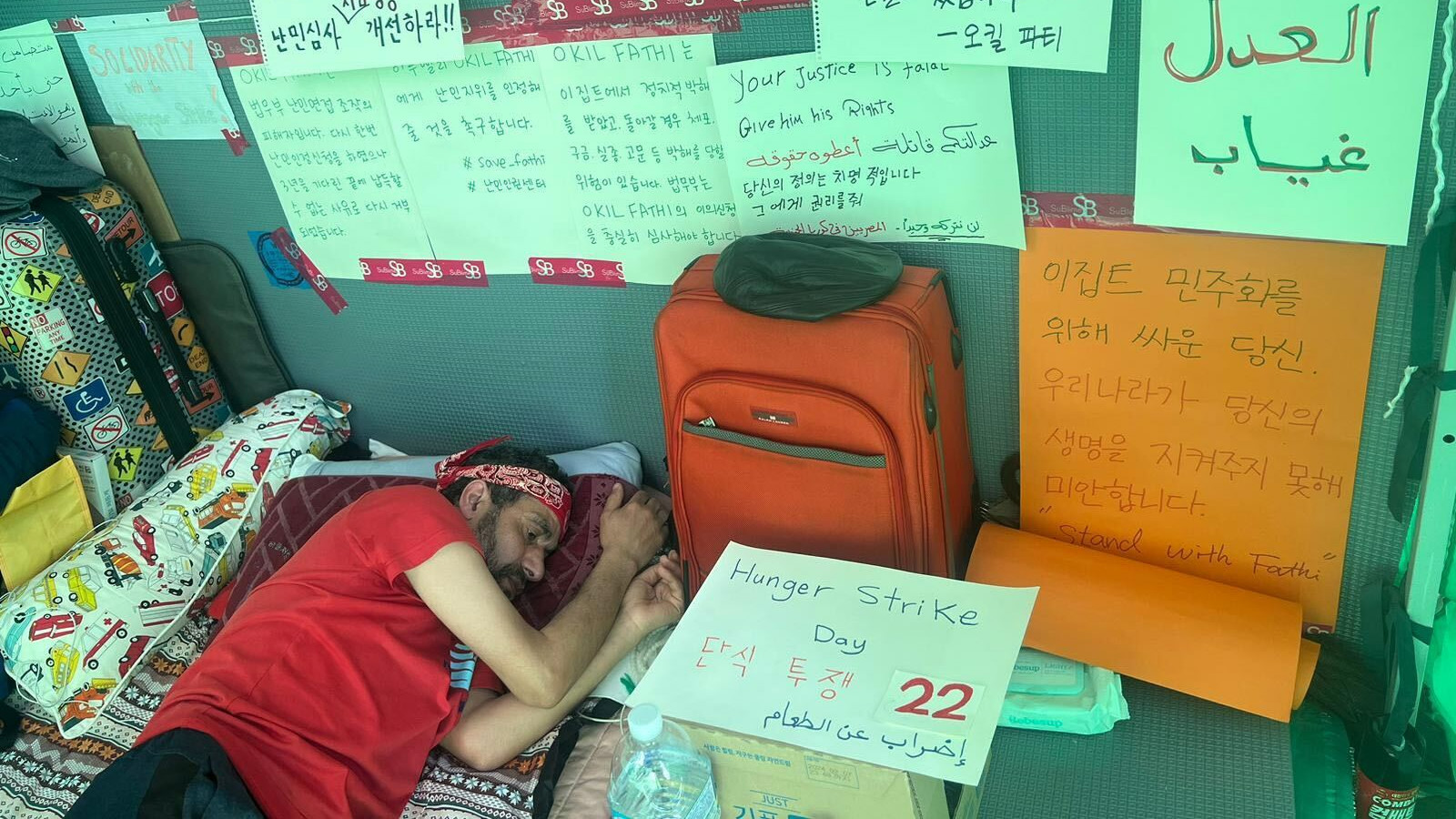

The condition of an Egyptian man has significantly worsened as he surpassed 20 days of a hunger strike during his sit-in outside the Ministry of Justice in Seoul, South Korea.

Fathi Okil, aged 52, initiated the hunger strike as a final and desperate measure to protest against the repeated denial of his political asylum application over a period of nine years. In a last-ditch effort to pressure the Korean authorities into granting his application, Okil started his strike 24 days ago after his plea was rejected for the third time.

Okil, who has camped in a tent outside the ministry in Seoul for six months, has been seeking asylum in South Korea since he fled Egypt in fear of political persecution in 2014.

He told Middle East Eye over the phone that he wears two pyjamas and a jumper and covers himself with a duvet to keep himself warm during Seoul's chilly nights.

"I only drink water and salt. I boil water to drink it hot, to warm myself inside the tent," he said.

Okil is stuck in South Korea with other Egyptians who have also been denied asylum. He has decided to launch a hunger strike "until death", as life has become unbearable.

"I lived terrible days in the past nine years. I slept in the streets, metro stations and parks. I ate from the rubbish at some point. Last Friday, I fell unconscious in my tent because of the cold," he said.

'I lived terrible days in the past nine years. I slept in the streets, metro stations and parks. I ate from the rubbish at some point'

- Fathi Okil, political activist

"Employees from the immigration department checked on me and asked for an ambulance, but I refused to be hospitalised."

Okil was a political activist from the Dakahlia governorate and a member of the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP), led by former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi.

In the summer of 2013, army chief Abdel Fattah el-Sisi led a military coup that ousted Morsi, Egypt's first democratically elected president, and has been in power ever since.

The FJP, which was formed by the Muslim Brotherhood, was dissolved and its members faced widespread persecution, with hundreds arrested and some tortured. Others fled to Europe, Turkey and some as far as Seoul.

Senior Muslim Brotherhood figures, including Morsi, were also detained.

Okil was detained for six months in Egypt for his opposition to the Sisi government, and after he was released in 2014 he fled to South Korea.

"I have been protesting in the tent for the past six months. I've lost 15 kilograms, and suffer from low blood sugar, and my hearing has weakened," he said.

"I have a headache, pain in my stomach, and shortness of breath... all my body is aching at the moment."

Okil's repeated pleas to the South Korean government to grant him asylum have so far fallen on deaf ears, and he now faces deportation.

He said he gave authorities copies of his FJP membership card, pictures of himself taking part in protests during the 2011 revolution in Egypt, and photos with senior party leaders, including detained MP Mohamed el-Beltagy and Mohammed Mahdi Akef, former head of the Muslim Brotherhood. The copies were also shared with MEE.

"I now face a deportation order, and I fear I will be sent back to Egypt," he said.

'Always anxious'

Since 2014, Okil has submitted three asylum applications, but they were all rejected. His status in the country does not allow him to legally work full-time.

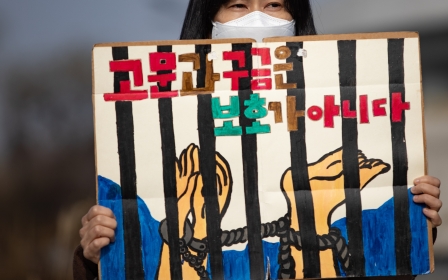

Asylum seekers are only allowed to be employed in manual labour fields, such as manufacturing, construction and agriculture. In the meantime, government support for asylum seekers is practically nonexistent.

In 2019, only 609 people - four percent of the number of refugee applicants in South Korea that year - received some form of financial support from the government, according to the Ministry of Justice’s most recent data.

"I worked here and there to support myself in menial jobs, but I was always anxious I would be caught and deported."

Okil's son was arrested in 2015 in Egypt, while he was in South Korea.

"When authorities in Egypt could not arrest me, they arrested my son, made up a drug case against him and locked him [up] for six years," he said.

Okil tried to travel to Italy in 2019, but was denied boarding a plane because he lacked the right document and a visa.

'They told me: "On 2 June we will give you a decision." I replied: "If you found me dead then give my body the asylum"

Okil said that South Korea deprived him of his "sense of humanity. They keep promising me. Last time, the immigration department's employee told me that: 'On 2 June we will give you a decision.' I replied: 'If you found me dead then give my body the asylum.'"

According to the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, the asylum acceptance rate in the country in 2o21 was just one percent.

Okil does not speak Korean and communicates with authorities through a translator and a lawyer from a Korean rights group.

Ahmed Attar, executive director of the London-based Egyptian Network for Human Rights, told MEE that Okil has suffered "clear and flagrant" violations of his rights as granted by international law.

"The Korean government must quickly end the suffering of the Egyptian citizen," Attar said.

"Okil resorted to the state of South Korea, hoping to find a safe haven away from the security pursuits and the threat to his security and safety by the Egyptian security authorities because of his political views and beliefs."

MEE has contacted the South Korean embassy in London for comment.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].