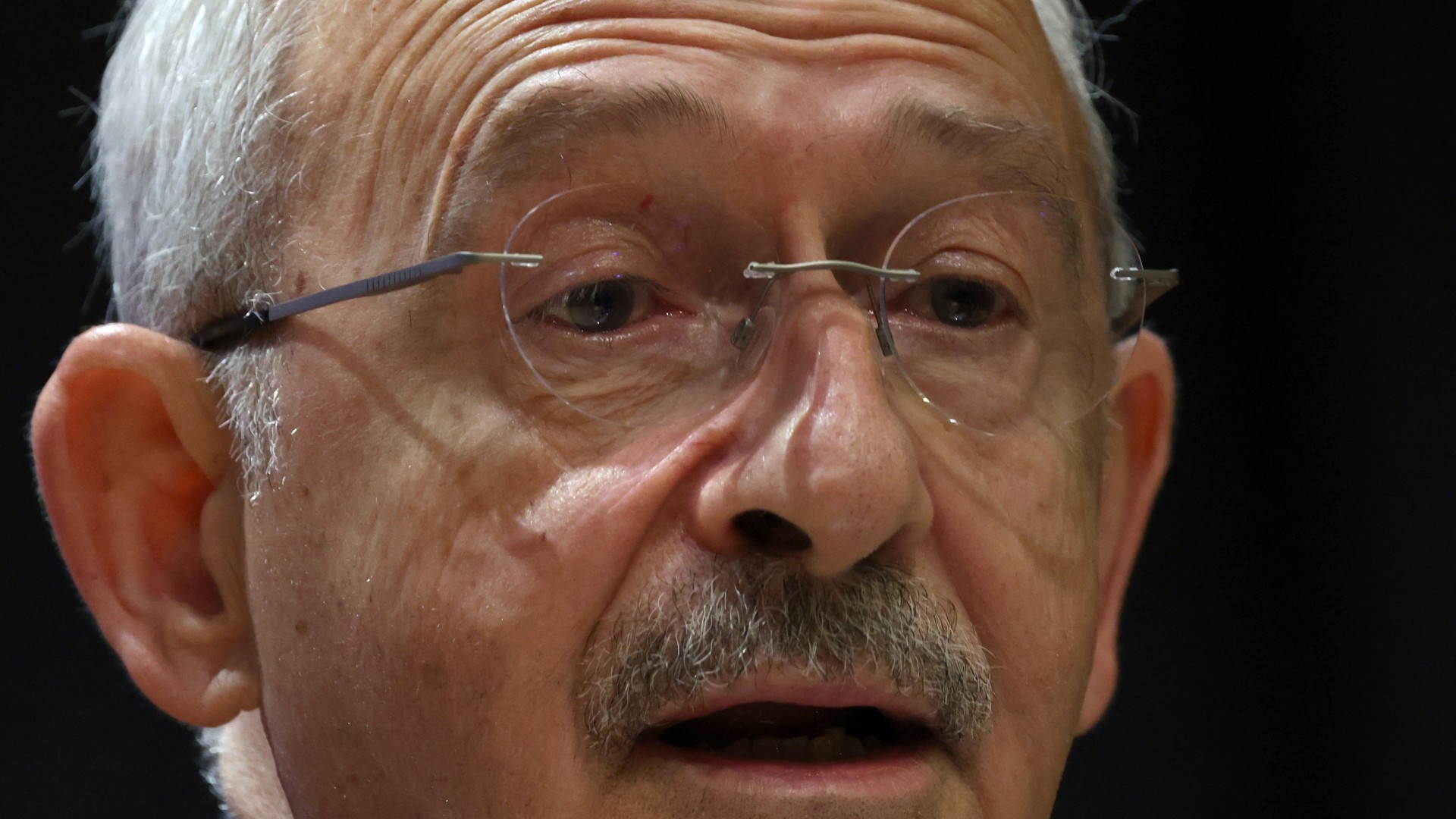

Turkey elections: Why did Kilicdaroglu lose?

When Kemal Kilicdaroglu was unveiled as the opposition's main presidential candidate, I found myself impressed by the crowds that had amassed outside the headquarters of the Islamist Felicity Party.

It was a sight to behold.

Islamists joined forces with Turkish nationalists, liberals and Kemalists to support Kilicdaroglu, the chairman of the Republican People's Party (CHP), despite their longstanding rivalry, which had persisted for decades.

There were high hopes placed on the 74-year-old. He had the potential to unify various political factions in an effort to unseat President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, after having transformed his party from an archaic, establishment entity that solely represented old-school Kemalism into a progressive centre-left social democratic force.

Heading into the polls, Erdogan appeared significantly weakened, due to a protracted economic crisis, a dismal human rights record and a botched response to the devastating February earthquakes.

After being in power for two decades, he seemed frail and politically vulnerable, unlike at any other time since 2014.

However, Kilicdaroglu still couldn't secure victory.

Naturally, it's easy to blame the defeated candidate and identify the obvious reasons for their failures. But we still need to delve into why the Turkish opposition couldn't successfully challenge a politician who appeared increasingly detached from economic and social realities.

I acknowledge that Erdogan enjoyed certain incumbent advantages, and the playing field was far from level, with the Turkish president utilising state resources to entice voters with the prospect of free household gas, salary increases, tax cuts and affordable loans.

He also resorted to a campaign that targeted minorities like the LGBTQ community and disseminated doctored images linking Kilicdaroglu to terrorists.

Nonetheless, Kilicdaroglu made some major blunders along the way.

Ineffective campaign

Kilicdaroglu ran an ineffective campaign that failed to convince voters that he was a superior alternative to Erdogan.

His campaign team, led by two people from the advertising industry, focused solely on marketing strategies and possibly underestimated the importance of public engagement.

While he did release nightly Twitter videos that conveyed his plans for the future, he refrained from making new pledges at rallies while on the campaign trail.

It’s now evident that he failed to penetrate the heartland of Anatolia and connect with urban conservatives, relying solely on social media support.

Oddly enough, a recent Facebook ad report revealed that Kilicdaroglu spent only a tenth of what pro-Erdogan groups spent on the social networking site.

Kilicdaroglu's policies were not translated effectively into campaign tools. Voters were unsure what Kilicdaroglu truly stood for, beyond his desire to oust Erdogan.

One could argue that Kilicdaroglu advocated for a return to a parliamentary political model, but such a political message failed to resonate with the electorate.

Kilicdaroglu also didn't position the country's dire economic situation as a pillar of his campaign, and neglected to discuss how he planned to rectify structural problems.

Instead, he opted for populism, making lofty promises such as increasing wages and pensions for workers in the public sector, pledging visa-free access to Europe for Turkish citizens within three months, hiring more teachers, technicians and engineers for villages, and even promising free electricity for agricultural towns.

When questioned about his economic policy, he declined to give clear answers, stating that he had assembled an all-star team of former bureaucrats, bankers and ministers who would fix everything. But who would be at the helm of power? Would it be former Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan or economy professor Bilge Yilmaz, who repeatedly criticised Babacan for proposing so-called "wrong policies"?

His officials failed to tour the region to present a united front on the economy, nor did they explain to the public their priorities for addressing issues such as unemployment, trade deficits, inflation and hunger.

Ultimately, Kilicdaroglu couldn't convince voters that he would implement a better economic policy capable of delivering tangible results.

Divided coalition

The divided Table of Six coalition also worked against Kilicdaroglu.

When Meral Aksener, the leader of the Good Party, briefly left the coalition due to her reluctance to support Kilicdaroglu as the joint candidate, Erdogan was busy leading a high-level meeting with experts to address future disasters like the 6 February earthquakes.

This episode overshadowed the suffering of millions of earthquake victims. Erdogan, who himself led an inadequate response to the earthquake emergency, appeared as a responsible leader genuinely concerned about pressing issues, while the six opposition leaders fought bitterly for political gains.

Kilicdaroglu's promise to assign eight vice presidential positions to different party leaders and mayors evoked fear among many who were reminded of similar coalition governments in the 90s, which collapsed one after the other.

Moreover, during individual rallies held by the political parties, including Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu, Kilicdaroglu's banners and pictures were noticeably absent, until the final two weeks before the 14 May election.

Political parties, except for the Felicity Party, failed to display Kilicdaroglu's posters on their buildings or actively campaign for the so-called joint candidate through their social media accounts.

This is why Erdogan held a distinct advantage over the opposition. He could criticise them for making empty promises and engaging in infighting. But his most potent weapon was Kilicdaroglu's unofficial alliance with the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), which shares ideological ties with Kurdish armed groups labelled as terrorists by the state.

Erdogan relentlessly attacked Kilicdaroglu for collaborating with terrorists, taking orders from Qandil, where the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) headquarters are located. He even screened doctored Kilicdaroglu campaign videos province by province, featuring endorsements from PKK leaders.

Kilicdaroglu's response was a single tweet which failed to address the issue seriously.

As the only leader in the political arena who was physically assaulted by the PKK, in northeastern Turkey in 2016, Kilicdaroglu failed to counter the illogical criticism that he was working for the PKK. He chose to remain silent, rather than refute the argument. Furthermore, he announced his intention to release former HDP co-chairman Selahattin Demirtas from prison, who in turn tweeted his support for Kilicdaroglu.

The HDP openly threw its weight behind Kilicdaroglu, which proved detrimental to his standing among Turkish nationalists in the west of the country. Kilicdaroglu's alliance with the HDP or the Kurds had worked effectively in the 2019 mayoral elections, where Erdogan lost Istanbul and Ankara due to the silent cooperation between the parties, without any official endorsement from the HDP.

The last opportunity

Additionally, Kilicdaroglu lacked an effective strategy for the runoff, which was appalling.

This contrasted starkly with Erdogan's campaign, which had prepared three advertisement videos, new slogans and posters well in advance.

Now we have an opposition leader who not only fails to acknowledge Erdogan's victory but also gives no hint of resigning following a defeat, which should be the norm in any democracy

Kilicdaroglu waited four days before emerging from the shadows after the first-round failure, and he resorted to becoming an ultra-nationalist leader opposing refugees, employing fear tactics to boost his chances.

Unfortunately, this approach not only appeared disingenuous coming from Kilicdaroglu, it also seemed like a last-ditch effort, a desperate strategy executed clumsily, and it was enough to alienate Kurdish voters due to his sudden alliance with a Turkish ultra-nationalist party.

The runoff results on 28 May did not come as a surprise to many.

The last opportunity for a meaningful change in Turkey's government through a broad alliance of parties, which could have improved democracy for the masses and addressed long-term economic issues, had vanished.

Now, we have an opposition leader who not only fails to acknowledge Erdogan's victory but also gives no hint of resigning following a defeat, which should be the norm in any democracy.

Some argue that he needs to remain as the chairman of the CHP to carry his alliance into next year's municipal elections and maintain major cities through his unifying tactics.

However, even then, he would still be a lame duck who has lost his magic.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].