Wagner insurrection: Western states should be careful what they wish for

One question puzzles me about the unrestrained glee with which Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin’s armed rebellion has been reported in Europe and the US. Which side are they rooting for?

Is it the tsar who invaded Ukraine under the delusion that his tanks would be greeted as liberators by Russian speakers? Or is it the catering billionaire whose mercenaries have terrorised Syria, Libya, the Central African Republic and Mali, and whose brutality makes Blackwater (on which the Wagner Group is modelled) look like a model of restraint?

Or do they want civil war to break out and the Russian Federation to break apart?

There is a fourth option, which I guarantee will not take place in at least a generation: that Russian President Vladimir Putin is replaced by another Boris Yeltsin simulacrum, such as, for instance, the imprisoned Alexei Navalny.

It was the West’s total support for Yeltsin, and the collapse of Russia under him, that led to Putin’s rise in the first place. It’s a conveniently forgotten fact that Putin was Yeltsin’s appointee as prime minister at a time when Russia was rocked by warring oligarchs. Putin owes his rise to power to The Family, not to the KGB.

By total support, I have this in mind: the last time armed conflict broke out on the streets of Moscow was in 1993. It was called a constitutional crisis between a Soviet hangover body, the Congress of People’s Deputies, and the presidency, but it was solved with tank fire.

Yeltsin ordered tanks to fire at the Russian White House. He had supreme difficulty finding tank crews to do this, and even when the guns were trained on the building in central Moscow, the crews were reluctant to fire on fellow Russians, let alone parliamentarians who refused to quit their chambers. They had to be prompted by snipers from the presidential bodyguard shooting at their own men.

Putin's powers

When it was all over and the White House was a burnt-out shell, many more bodies were taken from the building than were admitted in the official death toll. They were collected and taken away at night to a stadium behind the US embassy, which had a front-row view of everything that happened on that Sunday.

Nothing was said. The Economist ran a cover with the heading “A necessary evil”. After these bloody events, a new constitution transferred all executive powers to the presidency and created a much weaker, rubber-stamp parliament.

These changes formed the bedrock of the powers that Putin enjoys today. When these powers were first unveiled and debated, the West acted as their apologist, as it did for everything that happened under Yeltsin’s presidency.

Yeltsin himself had nightmares about what he did. He was depressed, drank and tried to take his own life, according to what his former bodyguard, Alexandr Korzhakov, told me.

The fear of civil war runs deep in Russia, but the prospect of the breakup of the Russian Federation has always been on the agenda of the neocon right

The fear of civil war runs deep in Russia, but the prospect of the breakup of the Russian Federation has always been on the agenda of the neocon right, because nothing is ever enough for them. The breakup of the Soviet Union was unfinished business. There is a large body of US, Polish and now Ukrainian opinion that says Russia must be “cut down to size” after the war is over.

This is mirrored by the Nato generals who say that the Russian armed forces should never again become strong enough to mount another adventure on this scale.

The Pentagon hovers between pragmatist and maximalist positions. It recognised the dangers of civil war last weekend and what could have happened to the command and control of Russia’s huge nuclear stockpile; and Washington also passed messages to Putin that it had nothing to do with Prigozhin’s uprising.

This was aimed at de-escalation. So too was the US advice to Ukraine not to mount covert raids into Russia while the mutiny was going on. But then, US intelligence sources leaked to the New York Times that Prigozhin had more support in the military than Putin now claims. They said that General Sergei Surovikin, variously known as the “butcher of Syria” and “General Armageddon”, the hardman who Putin brought in to lead the Ukraine campaign but later demoted when little was achieved, had advance knowledge of the rebellion.

Surovikin has since been detained in an ongoing purge, which is curious because Prigozhin is thus far, free.

Prigozhin's 'masterclass'

This is all intended to weaken Putin and encourage splits in the Russian military. Is this necessarily a wise thing to do?

Because it’s hard to make a case for Prigozhin. A former convict, hotdog vendor and billionaire catering chef turned boss of a private army with global reach, Prigozhin is a typical rags-to-riches creation of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

At least before his attempted insurrection, Wagner had become so big that it wielded all the power of a KGB directorate with none of the constraints, training or institutional discipline. If this were 19th-century Russia, Prigozhin would play the role of a muzhik - a plain-speaking peasant, despised and revered in equal measure by the educated, French-speaking urban elite, for somehow representing the soul of Russia.

His antics on Saturday were superficially attractive to a western audience. Wagner embarrassed the regular army. Prigozhin said his troops gave regular soldiers a “masterclass”. They took over Rostov-on-Don, the Centcom of the Russian war effort in Ukraine, and were greeted as heroes by the local population. “In Russian towns, civilians met us with Russian flags and the symbols of Wagner,” Prigozhin said.

He also had his supporters. Andrei Kartapolov, chairman of the Russian parliament’s defence committee, said Wagner fighters who took over the army headquarters “did not do anything reprehensible”.

“They didn’t offend anyone, they didn’t break anything,” he said. (In fact, they shot down six helicopters and a command-and-control aircraft.) “No one has the slightest claim against them - neither the residents of Rostov, nor the military personnel of the Southern Military District, nor the law enforcement agencies.”

Prigozhin further embarrassed Putin by contradicting the official reason for the Ukraine invasion. He said it had nothing to do with an existential threat to the Russian state and that the Russian war effort has been plagued by incompetence.

But if the Wagner columns had gone all the way to Red Square unopposed, and the National Guard had joined the insurrection, would that have meant an end to the war in Ukraine? Far from it. Prigozhin would have been lauded by ultra-nationalists as the man to finish the job and not be afraid to use tactical nukes to do it.

State propaganda

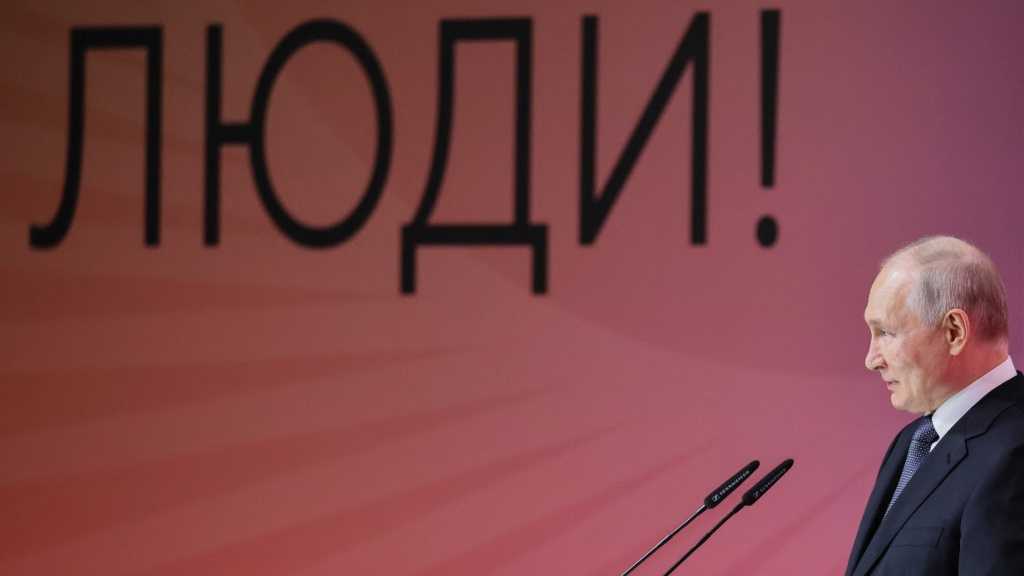

This brings us back to Putin, who does not represent a fixed point in the ideological stakes. He has shimmied from privatiser and Yeltsin loyalist, to a president keen to rub shoulders with former US President George W Bush and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, to a disgruntled nationalist, to a messianic restorer of Russia’s lost 18th-century empire.

His team of licensed pundits has accompanied him on this long journey. Most of the politicians and pundits wheeled out to shock a western audience - Dmitry Medvedev, Sergei Markov, Dmitri Kiselyov, Vitaly Naumkin, Sergei Karaganov, Fyodor Lukyanov - held radically different views about the West in the 1990s, when I first came across them as a correspondent in Russia. They appear to have sold themselves, body and soul, to Putin.

Medvedev would not have said there were no moral limits to stop Moscow from destroying undersea cables anytime when he was president. Quite the contrary, Medvedev was seen as suspiciously pro-western by Russia’s hawks.

Under his watch, Russia abstained from the UN resolution that paved the way for the invasion of Libya and the fall of Muammar Gaddafi, a move bitterly criticised by the hardliners. This debacle laid the foundations for Russia’s plans to return to the Middle East by intervening in Syria.

Kiselyov, a Channel One anchor, would not have suggested anytime in the 1990s that in retaliation for supporting Ukraine, Britain should be wiped out by a nuclear tsunami caused by the detonation of a Poseidon underwater drone off the coast of Lancashire.

Karaganov would not have written an article, clearly intended for a US audience, that Russia should lower its nuclear threshold. Karaganov argued that only by breaking the West’s will to maintain “its puppet regime” in Kyiv could Russia free itself from a yoke that has lasted five centuries.

“By pushing the West towards a catharsis and thus its elites towards abandoning their striving for hegemony, we will force them to back down before a global catastrophe occurs, thus avoiding it. Humanity will get a new chance for development.”

The war in Ukraine will drag on for years and no decisive victory will be achieved without breaking western will, he added: “Therefore, it is necessary to arouse the instinct of self-preservation that the West has lost and convince it that its attempts to wear Russia out by arming Ukrainians are counterproductive for the West itself. We will have to make nuclear deterrence a convincing argument again by lowering the threshold for the use of nuclear weapons set unacceptably high, and by rapidly but prudently moving up the deterrence-escalation ladder.”

Preemptive strike

Karaganov is no stranger to this subject, having studied nuclear strategy for much of his life. He counted about two dozen steps up the nuclear ladder, of which the first has already been taken by moving strategic rocket forces to Belarus.

He said things might get to the point where Moscow advises Russians to leave western capitals “that may become targets for strikes in countries that provide direct support to the puppet regime in Kyiv. The enemy must know that we are ready to deliver a preemptive strike in retaliation for all of its current and past acts of aggression, in order to prevent a slide into global thermonuclear war.”

An ultra-nationalist such as Prigozhin in power in the Kremlin would be a disaster for the region, but not as big as the break-up of the Russian Federation

Karaganov concedes that this would create problems for China, but not in their hearts: “If Russia delivered a nuclear strike, the Chinese would condemn it, but they would also rejoice at heart that a powerful blow has been dealt to the reputation and position of the United States.”

Is this a bluff, or the path Putin himself could take? No-one except Putin knows.

Which leads, finally, to the counter-offensive in Ukraine. Some time before the counter-offensive was launched, a British diplomat came to Ankara to sound out Turkish policy. He gave a curiously upbeat briefing to journalists and former Turkish diplomats.

He said the Russians were taking heavy casualties and running out of ammunition. There was frustration on the Russian side, and at the same time, the Ukrainians seemed to him to be shaping up to have “a real go” at a counter-offensive. It was as if he was describing the Second Test at Lords.

A former Turkish diplomat listening to him was more downbeat: “Russia can go on and on. This will affect Turkey in a very negative way. A battered Russia is good for Turkey; a broken Russia is bad. Turkey is pragmatic. Everything around us is falling apart.”

Ukraine quagmire

The British diplomat’s gung-ho briefing was mirrored by similarly optimistic assessments from military commentators. Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, former commanding officer of the 1st Royal Tank Regiment, said Russian defences would be nothing more than a “speed bump” on the way to Ukraine liberating Crimea. The Challenger 2 tank would cut through Russian lines like a knife through butter, the former tank commander asserted.

It has not felt like that. Ukrainian advances have been measured in hundreds of metres. They have taken heavy casualties, as have the Russians, but the lines themselves have not moved. Oleksiy Reznikov, Ukraine’s defence minister, told the Financial Times that the main event has yet to happen. We will see.

At the Ankara meeting, former Turkish diplomats challenged the whole notion of “breaking through” Russian lines. Would not a more apt analogy be a sponge of defences that reforms after each attack?

The options for the Ukraine war are all bad. An ultra-nationalist such as Prigozhin in power in the Kremlin would be a disaster for the region, but not as big of one as the break-up of the Russian Federation.

If the Russian lines hold by the onset of winter, we will inevitably see arguments emerging in Germany, France and Washington about the wisdom of continuing the war into a third year, and rifts growing between them and Poland and Kyiv. Putin could by then well be in a stronger position than he is today, producing greater quantities of cheaper ammunition than the western military-industrial complex can. That would translate into a stronger position at the negotiating table, which is the only place this is going to end.

If Ukrainian forces do break through Russian lines and approach Crimea, we should all pray that Putin does not reach for Karaganov's solution.

As for regime change in Moscow, the US and Europe should be careful what they wish for.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].