UK Labour party: The curious case of Britain's forgotten 2017 election

When the UK general election exit poll was released at 10pm on Thursday 8 June 2017, no one was more stunned than senior staffers at Labour party HQ.

“They are cheering and we are silent and grey-faced,” texted one to a WhatsApp group, in comments that later found their way into the media. “Opposite to what I had been working towards for the last couple of years!”

Labour’s bureaucracy was dominated by the right wing of the party. They had assumed that the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader in 2015 would lead to electoral armageddon. It was a view that was widely shared, which was precisely why the Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May had called an early election seven weeks before.

Labour had begun the campaign on just 25 percent in the polls. Yet on polling day it hit 40 percent, depriving May of an overall majority.

Corbyn had faced almost universal hostility from the British media and had had to fend off repeated plots to oust him by his own parliamentary party.

“The whole of the political world was … turned upside down,” wrote Lewis Goodall, political correspondent of Sky News. “Our jaws hit the floor.”

Memory of 2017 buried

Six years later, not only is Corbyn no longer Labour leader, he has been suspended from the parliamentary party and banned from standing as a Labour candidate in Islington North, where he has been an MP for 40 years.

He is routinely referred to as one of the most disastrous leaders in Labour’s history. And the entire British political-media class appears determined to bury the memory of 2017, along with any lessons that might be learned from it.

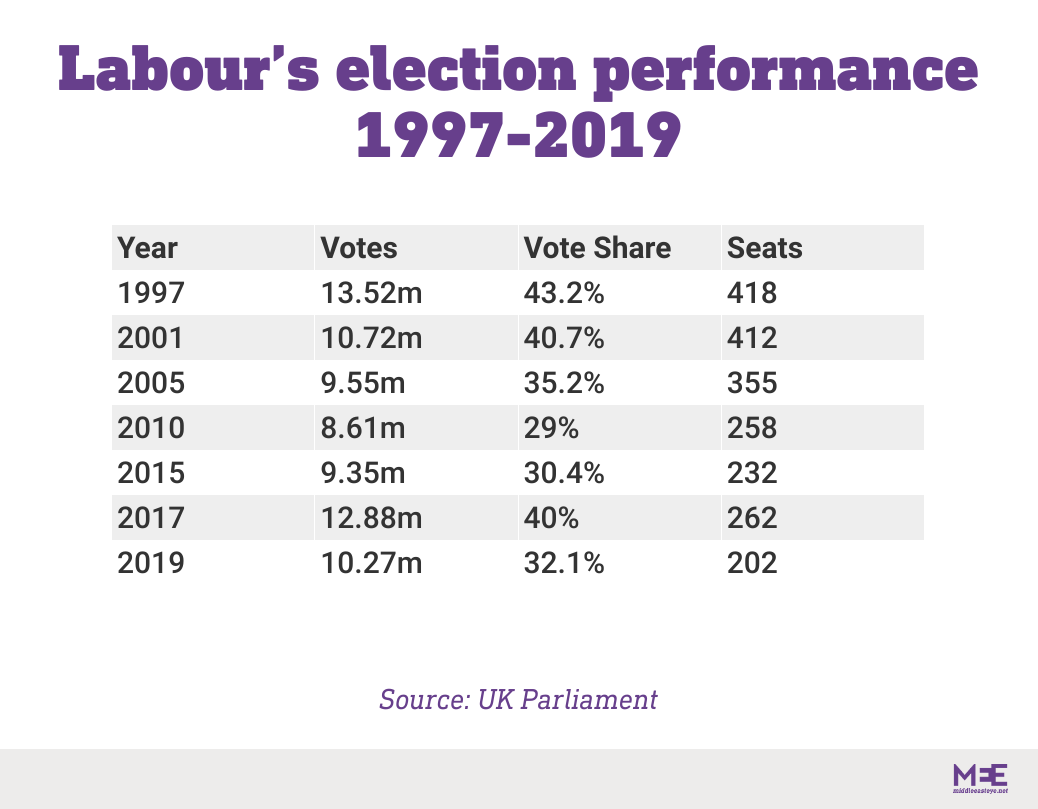

A Martian arriving on Earth and simply looking at the hard statistics of Labour's election performances from 1997 till 2019 would be mystified. Here they are:

The vicissitudes of support for the centrist Liberal Democrats and the pro-Brexit UK Independence Party (Ukip) mean the elections of 2010, 2015 and 2017 are not directly comparable.

The much-maligned Theresa May also saw a sharp increase in her party’s vote share in 2017.

But not by as much as Corbyn. And the main difference with 2015 was that, with Brexit achieved, the 12.6 percent who’d voted for Ukip were widely expected to switch back to the Conservatives.

Labour’s support leapt by 10 percentage points. And in terms of votes cast, the party was just a few hundred thousand short of Tony Blair’s total in 1997, when, although the electorate was a fraction smaller, the turnout had been higher.

Vision of social justice

Corbyn presented a vision of social justice and reform that many clearly found inspiring, particularly the young. Sixty-two percent of 18-to-24-year-olds voted Labour.

Two years of vicious, relentless character assassination followed in which, to its shame, the supposedly impartial BBC joined.

It took its toll. By the election of 2019, there is no question that Corbyn was unpopular with many voters and a drag on the fortunes of his party.

Even then, Labour's vote share was higher than it had been in 2010 and 2015 and, if pensioners are excluded, the party actually won.

Corbyn was also peculiarly ill-served by the vagaries of Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system.

In 2017, he’d come within 0.7 percentage points of Blair’s vote share in 2001. But where Blair won 412 seats and a landslide victory, Corbyn won just 262.

In 2019, Corbyn’s share of seats - 31.1 percent - was actually smaller than his share of the vote (32.1 percent), the only time this has happened to the Labour Party since the Second World War.

A key factor in his defeat was the belief among many Brexit-supporting Labour voters that the party would overturn the 2016 referendum. It’s galling for Corbyn that his desperate attempts to cobble a compromise were undermined by support for a second referendum from his own Shadow Brexit Secretary Keir Starmer - the man who succeeded him as leader, and now firmly opposes any reopening of the Brexit issue.

Vicious purge

Corbyn had nevertheless achieved two things. Firstly, he overturned the consensus on austerity which had dominated British politics since the financial crash of 2008.

Secondly, he’d dealt a mortal blow to the certainties of triangulation - the belief, which had held sway for the previous 30 years, that left-wing parties could only achieve power by cleaving as closely as possible to the centre ground.

Combined with Bernie Sanders’s run for the US presidency in 2016, it opened up the possibility that radical politics could enter the mainstream.

Yet today it is as if it never happened.

Having campaigned on a pledge to end factionalism and bring the party together, Starmer launched a vicious purge of the left, blaming it for all of the Labour Party’s ills.

At the same time, he led a headlong retreat back to the discredited dogmas of austerity and triangulation.

As if operating on muscle memory, the British media obediently fell into line.

“Keir Starmer is hard-working and methodical,” Liz Bates, political reporter for Sky News, recently told her viewers. “He saw where the Labour party was at and where it needed to be… He’s moved the party into the centre ground because he knows that that is where political parties win elections.”

Fact, not opinion, apparently.

Wilful amnesia

Following Labour’s disastrous defeat in the May 2021 Hartlepool byelection, shadow cabinet member Steve Reed declared that the problem remained Corbyn - who had stood down more than a year before - and that Labour hadn’t “changed enough” from the party that voters “comprehensively rejected in 2019”.

But Labour under Corbyn had won Hartlepool in both 2017 and 2019 - in 2017 with almost twice the share of the vote the party gained at the byelection in 2021.

It made no sense. Yet political reporters solemnly nodded along.

The entire British political-media class appeared to be gripped by a wilful amnesia.

Starmer supporters would point out that the Labour Party has been ahead in the polls by a solid 20 points for much of the last year. His opponents would counter this reflects the unpopularity of the Conservatives rather than any enthusiasm for Labour.

Certainly when it comes into contact with the electorate, the party performs rather less impressively. The May 2022 local election results, when extrapolated to national vote share, gave Labour just 35 percent - well below what Corbyn achieved in 2017 - at a time, mid-term, when the opposition would be expected to be performing strongly.

Local council byelections also provide a fascinating study. They tend to feature very low turnouts. But there have been more than 500 since the 2019 election.

Remarkably, on average, the Labour vote share has dropped by 2.2 percentage points - which is worse than the Conservatives.

There is a profound dissonance between the way the electorate sees the world, and the way politicians and journalists tell them they see the world

A recent poll showed Corbyn to be the most popular politician in Britain. Admittedly, the bar is low. He won with an approval rating of just 30 percent.

But perhaps more startling was his approval rating of 55 percent among Labour voters. This compared with a figure of just 40 percent for Starmer.

For a politician who, as far as the British media is concerned, has been dead and buried for almost four years, this is astonishing.

The electorate, it would appear, has a mind of its own. And there is a profound and jarring dissonance between the way they see the world, and the way politicians and journalists tell them they see the world.

Deep discontent with status quo

The determination to erase 2017 from the national psyche has two adverse effects.

Firstly, the great upsurge of enthusiasm and optimism that marked the early years of Corbyn’s leadership has been throttled. Membership of the Labour Party, which had soared to 564,000 under Corbyn, has plunged to fewer than 400,000 - a development welcomed by Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves as a “good thing”.

Those leaving “should never have joined the Labour Party”, she said.

To respond to a sharp rise in the membership of your own party by seeking to expel or repel as many as possible is perverse, and surely unique in the annals of modern politics.

Effectively an entire generation has been told their engagement with the political process is not welcome, unless it be on terms set by the Labour right.

Secondly - it limits the ability of the country to have an intelligent conversation about the many deep, structural problems that confront it.

The reasons people turned out in such numbers to vote for Corbyn in 2017 are many and complex.

But one thing is clear. Combined with the Brexit referendum of 2016, it revealed a deep discontent with the status quo and hostility to the political establishment.

Now the people of Britain find themselves presented with a choice between an entirely discredited government and an opposition whose main concern, it seems, is to indulge in performative “grown-upness” and to demonstrate slavish adherence to the very conventions and orthodoxies that created the mess in the first place.

British politics isn’t working.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].