How Brics is looking to challenge the western order in the Middle East

With Brics set to welcome Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iran and the United Arab Emirates to its number, the collaborative group of nations is about to get a major boost in the international arena.

Not only is Saudi Arabia the world’s top oil exporter, but it’s also the seat of Islam's holiest sites, making the decision to invite the kingdom an important economic, political and highly symbolic move for the bloc that has so far lacked a Muslim country.

Egypt, the most populous Arab country, will be another feather in the cap of the Brics - whose name is an acronym of the current and original members Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Egypt's presence boosts the bloc's image as one that is inclusive and representative of various civilisations.

And in a nod to the country's increasing economic and political influence, the UAE looks set to cement its reputation as a global power broker by joining the group, which will seek to use its influence.

Across the Gulf, Iran's addition is also meant to carefully manage the power equilibrium between Arab countries and Tehran. China has already signed a 25-year Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement with Iran estimated to be worth around $400bn.

And since the Ukraine war, Iran and Russia have drawn closer - united in part by the sanctions levied at them by the West. Tehran's inclusion also burnishes its global influence, something it has sought to increase.

With Ethiopia and Argentina joining these four Middle Eastern countries as the Brics' newest members, a conscious effort to reorganise global leadership is in play. Together they represent about 45 percent of the world’s population and more than a third of global GDP.

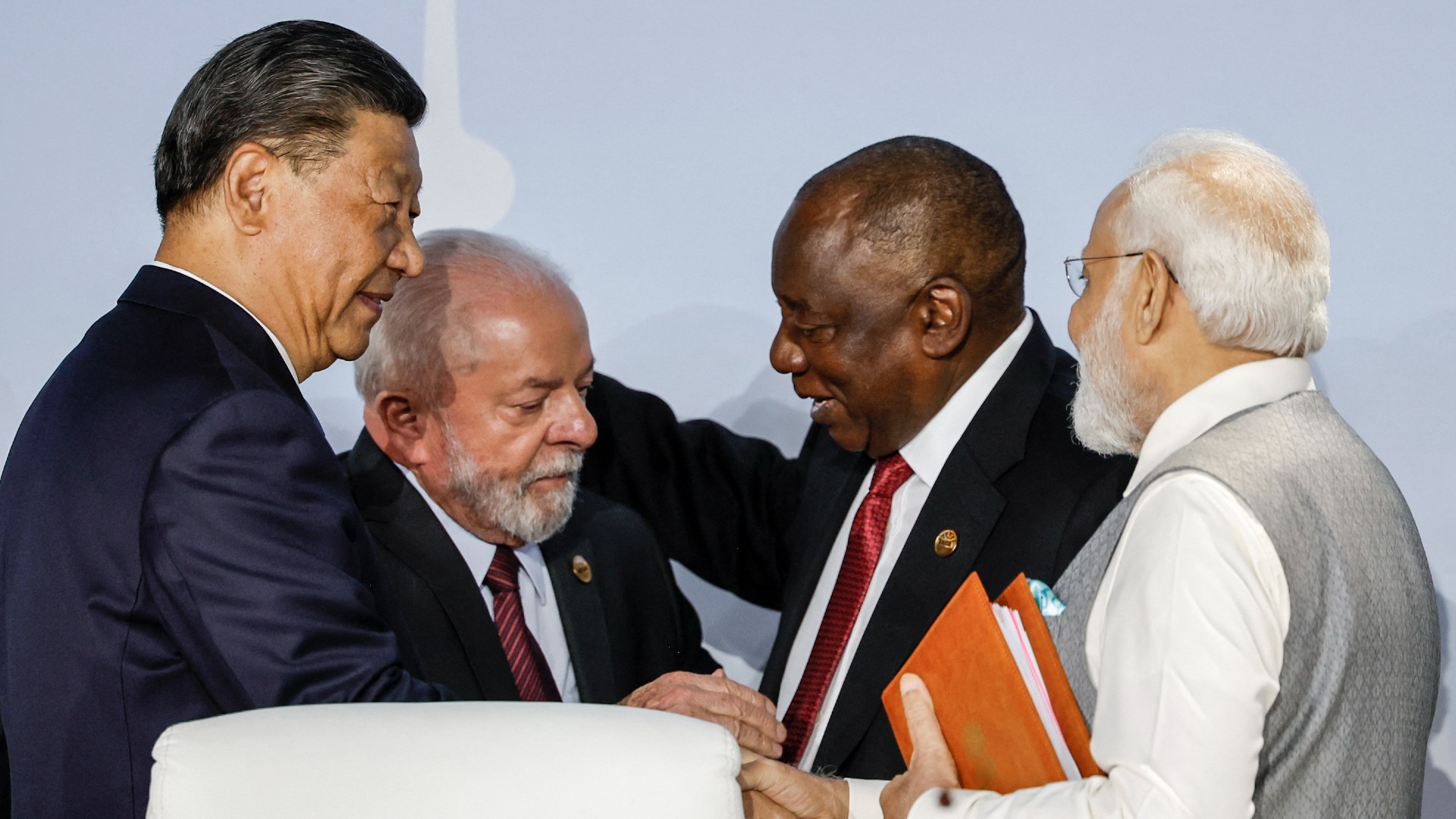

As Brics leaders gathered this week in South Africa's Johannesburg, a queue of countries from the Middle East and North Africa increasingly expressed a desire to join the group, which is seen as the developing world's answer to the G7.

Algeria, Bahrain, Kuwait, Morocco and Palestine are just some of the countries that have publicly expressed a desire to join.

For the Middle East and North Africa, there will likely be political, economic and social ramifications from this realignment, potentially undermining US power in the process.

One Bric at a time

Evidence of non-western countries playing a decisive role in Middle Eastern diplomatic affairs could already be seen before the Brics' expansion.

In March, China brokered a landmark diplomatic breakthrough between Saudi Arabia and Iran, two bitter regional rivals, demonstrating how far the country’s influence in the region has come and taking Washington by surprise in the process.

Notably, the decision to ask Saudi Arabia to become a permanent member of the group was pushed by China in particular, followed by Russia and Brazil, according to reports.

“Gulf countries are diversifying their political and economic relations as the world order becomes increasingly multipolar,” Anna Jacobs, a senior Gulf analyst at the International Crisis Group, told Middle East Eye.

“Economic and political diversification, balancing relations between global powers, and avoiding the pitfalls of great power competition are all essential pillars of Gulf countries' foreign policies today.”

Increasingly, China exports more to the developing world than to the EU, US and Japan combined, an important shift in global economics that’s also shaping international politics.

And with the drive towards Brics including staunch and longstanding US allies such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Arab countries are showing a growing ambition to chart their own path in the world.

“The US can't really do much about it,” said Jacobs. “This is a function of the changing multipolar world order and Gulf states are reacting in a way that makes sense for their national interests.”

'Saudi Arabia is seeking to become a heavyweight middle power, and increasing ties with both East and West is an important mechanism for doing this'

- Anna Jacobs, International Crisis Group

For the UAE and Saudi Arabia, that has meant forging closer relations with China and Russia where interests converge, much to the chagrin of the US.

Many in the Global South believe that the US-led international order protects, promotes and enlarges western interests around the world.

For some, including Middle Eastern countries, the Brics grouping gives hope that they can project their interests in an emerging multipolar order and perhaps even carve out their own sphere of influence.

“Saudi Arabia especially is seeking to become a heavyweight middle power, and increasing ties with both East and West is an important mechanism for doing this,” said Jacobs.

While Gulf states have made it “clear that the US is their primary external security partner at present” said Jacobs, the reality is that “Gulf states and their economic interests are increasingly in the east and with the developing world”.

A shift towards Brics

The drive to join the Brics also reflects a nervousness amongst Middle Eastern countries about the power the US exercises over their economic and political development.

In June, JPMorgan, the biggest US bank, warned that “some signs of de-dollarization are emerging”.

Since 1971, the supremacy of the US dollar system has been a ubiquitous feature of the global financial system, underpinned by a deal between US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and King Faisal of Saudi Arabia that created the petrodollar system.

“Being married to the dollar means maintaining a dependency upon economic systems that are ultimately controlled by the US and, to a lesser extent, other western nations,” said Jalel Harchaoui, associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute.

The power the US dollar confers on Washington has become increasingly clear in recent years, in particular its use in sanctioning countries and trade wars.

US weaponisation of the dollar led to Gita Gopinath, the IMF’s first deputy managing director, warning that in time it might erode its role in the world financial system.

“For that reason, many Global South nations are attracted to the concept of belonging to the Brics club,” said Harchaoui.

Saudi Arabia’s finance minister, Mohammed al-Jadaan, announced earlier this year that the country was considering trading in other countries alongside the US dollar, something the kingdom hasn’t done in half a century.

“Among Arab nations, Egypt, Algeria and, most recently, Saudi Arabia showed interest in a Brics currency or currency-swap mechanism that makes it possible to bypass the greenback entirely,” added Harchaoui.

The Bric countries have already discussed creating a reserve currency that might be backed by gold, which would be a historic return to the gold standard.

That Saudi Arabia could again be part of this process after helping forge the dollar's dominance 50 years ago is a tentative indicator that the US-led West may be losing its ability to stamp its authority in the region.

Arab countries joining Brics, however, does not suggest they are choosing any particular order.

“Arab and other countries like the idea of not having to choose between the three poles that the world has right now: the US, Russia, and China,” said Harchaoui.

'Because the US is still extraordinarily powerful, this translates into a shift towards Brics, even though the reality of all this isn’t quite there yet'

- Jalel Harchaoui, Royal United Services Institute

“Because the US is still extraordinarily powerful, this translates into a shift towards Brics, even though the reality of all this isn’t quite there yet.”

Countries like Egypt have practical reasons for looking for alternative methods to conduct their trade using currencies and financial systems other than the dollar.

“A country like Egypt sees no reason why it should face great difficulty buying wheat from Russia simply because Putin’s aggression against Ukraine is condemned by Washington,” said Harchaoui.

Algeria faces a similar dilemma, finding it difficult to trade with other developing economies because of the US hold over international trade.

“Algeria would love to purchase weapons or order a nuclear plant from China or Russia without any dollars changing hands,” Harchaoui noted, but “right now, this is not easy at all”.

Post-Ukraine order

The war in Ukraine might arguably have given Brics a new burst of energy.

Many in the Global South, and in particular the Middle East, have either stayed neutral in the conflict or even cooperated with Russia when needed.

But the Arab world is also looking to express disagreements with the US-led western order in ways that might encourage Washington to sit down and listen to those countries' interests.

'Arab countries’ Brics candidacy speaks much about a desire to rebalance ties with the overall West and seek alternative partners than just the US'

- Zine Ghebouli, European Council on Foreign Relations

“The hype of Arab countries about joining the Brics is an extension of a political desire to diversify economic partners in the wake of the Ukraine war,” said Zine Ghebouli, a visiting fellow with the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“Arab countries want to mark their disagreement with the new emerging Cold War and international hegemony.”

Saudi and UAE leaders are increasingly confident in playing hardball with the US and even diverging from Washington when it doesn’t suit them.

Riyadh even worked with Russia to cut oil production in 2022, in a bid to raise prices that drew an angry response from Washington.

“I think Arab countries’ Brics candidacy speaks much about a desire to rebalance ties with the overall West and seek alternative partners than just the relationship with the US,” Ghebouli told MEE, adding that “Arab countries are also sending a message to the western world, which could mean rejection of certain development policies.

“However, the Brics is unlikely to replace western partners. The western status in the Arab region is here to stay even if it is increasingly challenged,” Ghebouli added.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].