Football versus the Egyptian State

Abdallah can hardly speak about the night he planned to watch his favourite team run the football field. Instead Abdallah and his friends ended up running away from death, leaving behind the corpses of at least 30 fellow supporters of the Zamalek Football Club.

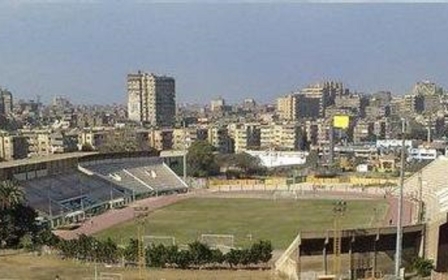

Boudi Tiger - Abdallah’s nickname in the Ultras - reached Cairo’s Air Defence Stadium a few hours before the beginning of the match and walked with his friends toward the main gate through a 4-metres-wide cage made of iron bars and barbed wire.

It was the first time that supporters were allowed to attend a game since 72 fans of the other main football team in the country, al-Ahly, had been massacred at the end of a match in Port Said on 1 February 2012.

“Once we were inside the cage, police just told us that we were not allowed to enter,” he recalled. “We showed them the tickets for the game, but they just stood there and started beating us up with sticks, laughing.”

Unable to move forward or retreat, as people unaware of what was happening at the front continued to amass in the tunnel, Abdallah thought that “there were three things that could have killed us. The amount of people who were inside, teargas, or birdshot pellets shot against us.” In the end, it was all three that lead to fatalities.

Forensic examinations carried out on 19 bodies confirmed that the reasons for the death were “suffocation, stampeding or pressure on the respiratory organs,” said Mohamed Lotfy, Executive Director of the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedom. “There were people injured by shotgun pellets or birdshots, but no victims of gunfire,” he added.

Egyptian authorities and the General Prosecutor quickly dismissed any responsibility of the security forces in the incident, labelling it as a simple “stampede”.

Boudi Tiger, however, does not have any doubt regarding the responsibility of the security forces. “It was like a game for them, they shot one tear gas canister inside the cage, and before the smoke would subside, they would shoot another one.”

“Let’s say that they really wanted to manage the crowd and prevent us from entering,” said another young Zamalek supporter, Mohamed. “Security forces could have just shot in the air,” he said. Instead, “a guy tried to pull up one of the flares we use for our dances and wave it in the air to signal people behind us to retreat. He did not even light it,” he recalled. “As soon as he put his hands up, police started shooting teargas like crazy against us, inside the cages.”

What Mohamed could hardly explain was why “when some of us managed to escape and run away, police chased us and kept shooting at us, over and over.” The stadium, he explained, is in the middle of the desert and there was nowhere to run.

Luckily, he managed to stop a car and run away to safety, leaving his friends behind. He said he felt ashamed of doing so. For they were more than just fellow football supporters.

When Mohamed moved from Suez to Cairo to study at university, he soon found a new family in the Ultras White Knights, Zamalek’s organised supporters. Despite previously living miles away from them, over the years their common passion for the game and the team had turned into a special relationship that surpassed friendship. Ultras consider each other comrades and brothers. Loyalty to the group and to the team, together with respect for the “capos” - the leaders of each Ultras section - is of the utmost importance.

Organised groups of diehard football fans based on the model of Italian Ultras or English Hooligans are relatively new to Egypt. The first group was created in 2007 by al-Ahly fans - Egypt’s most successful team - who had lived abroad and returned to Cairo. They imported the jargon and the idea of organised cohorts of supporters who would support their team chanting, lighting up fireworks, organising choreographed numbers, spreading their club’s logo through graffiti around the city’s walls or wearing their team’s colours.

“The sense of community that Ultras share lies in the passion for the sport, the passion for the club and the hatred towards police forces,” explained Professor James Dorsey of the Nanyang Technological University of Singapore.

In the last 4 years of Mubarak’s regime, tens of thousands of people joined Ultras groups. They all came from different areas, social classes and backgrounds, but “what they really wanted was to come down on security forces. They share the passion for the game and for the club, but the face of the regime to them were the security forces,” said Dorsey.

Then, the 25 January revolution broke out and rival groups put aside their differences to join demonstrators in Tahrir. “We were adversaries, but we all came from the same areas, we used to have meetings one next to each other and we all hated the police,” explained Abdu, a former Ahlawy supporter from Matareya - a working class neighbourhood where some claim Ultras groups first originated.

Experienced in clashing with the security forces inside and outside stadiums, Ultras Ahlawy and Zamalek’s White Knights served as the “bodyguards of Tahrir”, and as the protesters’ elite forces in fights with the police.

When 72 Ultras Ahlawy were massacred in the Port Said stadium on 1 February 2012, fans of al-Ahly and Zamalek joined forces once again and rioted against the Ministry of Interior, whom they deemed responsible for the killings. Ultras groups not only accused security forces of being complicit in the tragedy, but considered it an act of “premeditated murder,” or an act of revenge orchestrated by the police to punish the football supporters for their involvement in the revolution.

The riots that ensued, however, signalled the peak of the Ultras’ political involvement. On the wake of the first democratic presidential elections in June 2012, the fan-base split between supporters of the different candidates as political differences arose. Eventually, they sporadically joined forces to riot once again in events related to the Port Said massacre and the acquittal of security officers in the related case.

However, then President Mohamed Morsi’s term and his ouster on 3 July 2013, proved so divisive that Ultras members were split between the two fields. On one side, pro-Morsi Ultras joined the Raba’a sit-in, on the other pro-Sisi Ultras would protest in Tahrir.

“Political thinking within the movement runs from right-wing to left-wing, that is why they cannot translate their activities into politics and well political organised groups,” explained Professor Dorsey. “But they are surely capable of being a pressure group, and they have demonstrated it in the past,” he added.

But the world in which the Ultras appeared as heroic figures, capable of attracting the empathy of the population, seems to be long gone. While the massacre outside the Air Defence Stadium unfolded, people in the streets kept enjoying the match that was being played inside.

“Ultras chant in the same way, they keep the same attitude towards the state, and they went back to focus just on football. What really changed is the context where they operate. In 2011 they helped people fight police forces, so they were heroes. But now that the priority is stability, people seem to not support them anymore,” said Lotfy.

“I don’t know why they are doing this in this time when they need people to support them. I think it’s a blood feud against youth,” said Casper, an Ultras Ahlawy who lost a friend outside the stadium.

The Ultras themselves, seem to acknowledge the change. Three years ago, right after the Port Said massacre, they all rushed to call for revenge of their friends and rallied together in downtown Cairo, eventually trying to storm the Ministry of Interior. Today, they largely remained silent or switched off their phones.

Abdel Rahman was at the stadium with Mohamed, moments before the stampede. When reached by phone and asked to describe what happened, he started talking about the match. “We deserved to win, but the referee was really bad.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].