Beirut street art: Caught in the crossfire

BEIRUT - In a bid to ease tensions, a deal was brokered last week between Hezbollah and its rival, the Sunni-led Future movement, to remove all political posters belonging to both parties from Beirut and beyond.

The move to strip the streets of political posters was welcomed by residents of the capital. The city’s Governor, Ziad Chebib, was quoted as saying: “There were no objections, people were welcoming to us and about the campaign”.

But the move quickly had unintended consequences.

Beirut’s municipal authorities interpreted the political poster deal to mean that graffiti and street art - the vast majority of which stands overtly against sectarianism and the rhetoric peddled by major political parties - must also be removed from the city’s walls.

And just like that a large mural, roughly translating to “You are either free or you are not at all”, created by well-known local graffiti crew Ashekman and local NGO MARCH was painted over and many others like it slated for removal.

Unsurprisingly, the decision caused a backlash online. “Today, civil society in Lebanon was yet again silenced in favour of political compromises,” wrote MARCH on its Facebook page. Ashekman also fired back on social media, saying: “Let them bully the outlaws and thugs, not the graffiti artists. Our spray cans are stronger than their authority.”

The backlash soon paid off. Under pressure from MARCH and other civil society groups that all strongly denounced the move and worked to stir up public outrage, Beirut’s governor admitted late on Wednesday that erasing the mural was a mistake.

MARCH has now said that Ashekman will soon repaint a fresh mural, but the strong outcry is telling of deeper tension brewing on Beirut’s streets and its walls and a deeply committed drive by the artistic community to make a change.

The war of the walls

The omnipresence of political posters has been a fixture of Beirut’s streets for decades. The allegiance of different neighbourhoods has traditionally been clear through the display of banners and photos celebrating a party leader or glorifying fallen martyrs.

In some cases, political parties rented out prime billboard space, while in others residents would display their political allegiances from their own windows, walls and roofs.

The result is that these posters have become more a route through which parties compete for symbolic influence than a centralised propaganda tool.

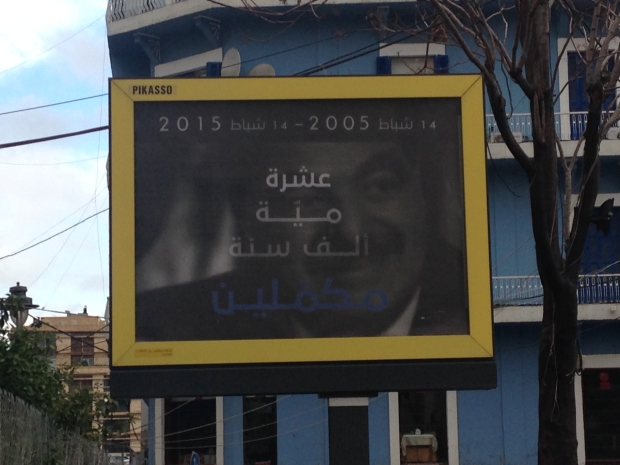

Despite the decision to ban posters and insignia in the streets, however, few believe that the parties will stop expressing themselves in public spaces entirely. Friday marks the 10th anniversary of the assassination of former Prime Minister and head of the Future party, Rafiq Hariri. Billboards commemorating the occasion of his death can be found across Beirut.

These billboards are likely to fuel divisions as the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, a controversial UN court set up to investigate the murder has accused Hezbollah members of involvement in the as yet unresolved 2005 murder.

Such visual materials play an important part in the life of Lebanese cities, where place, identity, and politics have a long (and bloody) history of interconnectedness.

The war over symbolism has on occasion spilled into actual violence. In 2012, three people were killed and at least four wounded when a group supporting Sunni Salafi preacher Ahmad al-Assir tore up a picture of Hezbollah’s Secretary-General, Hassan Nasrallah.

Most of the city’s murals that came under attack over the last 10 days, however, have sprung up in response to this endless cycle of political bickering. They have tried, for the most part, to act as counterweights to images of political leaders and to beautify parts of the city long abandoned by municipal leaders who have repeatedly chosen to destroy the city’s cultural heritage and seem determined to let row after row of flashy, and often vulgar, apartment buildings spring up instead.

Part of the solution

Ayla Hibri, a photographer now living in Sao Paulo and one of Beirut’s earliest stencil and tag artists, was first motivated to turn to street art out of a desire to lighten the mood of the capital.

“Remember how there were pictures of all those dead people on the walls? Martyrs and politicians?” she told Middle East Eye. “I wanted to change the mood of the city. Make it lighter”.

Many of Beirut’s street artists cite the need to react to the suffocating political situation or simply embellish their city as their driving force.

Jubran Elias, a founding member of the Dihzayners collective, now famous for painting staircases across the capital said: “The idea came from wanting to beautify and make Beirut more colourful… We’re going around in a cycle of wars - the new generation is just expressing itself through art more.”

Yazan Halwani, one of Beirut’s best-known muralists, creates many of his pieces with the express intent of representing unifying figures from Lebanese culture and history, which he says are designed to act as a contrast to the polarising political figures that usually inhabit the city’s spaces.

“Whenever I paint, I remove posters of politicians from the walls on purpose,” Halwani said. “These politicians are kind of conquering our urban landscape. They do it so well that anyone growing up in this city will think that they are the masters of the country.”

His famed piece featuring the face of author Jubran Khalil Jubran on a bank note, was one of those slated for demolition until this week, but while Halwani’s message might be a political one, it aims to rise above politics in modern-day Lebanon.

“Putting these cultural figures on banknotes would make them higher than politicians and I would think that it might be annoying for them,” Halwani said. “This is why I actually painted the piece.”

“If you had actually adopted this design, you would have a cultural figure and people would want to become like Jubran Khalil Jubran and not [Lebanese Forces leader] Samir Geagea or Hassan Nasrallah or [Free Patriotic Movement leader] Michel Aoun or [Future Movement head Saad] Hariri.”

Although the need to counter images of politicians may seem less pressing in light of the recent decision to ban them, such posters are no more than a visible symptom of complex and persistent divides within Lebanon – which some Beirut residents say they want to heal.

Jubran Elias, of the Dihzayners collective known for involving local communities in their projects, said: “People thank us and say they’ll pray for us” because they think our message needs to be promoted.

Similarly, Ayla Hibri a Lebanese photographer said that she was met with widespread support when she created pieces in the street calling for peace and change.

“A lot of people would tell us to go for it. Even adults would stop and say: ‘amazing, keep doing this - we need this’.”

In a media climate often hijacked by the main, sect-based parties, artists often complain that there is little room to express dissent. Instead, many have chosen to take to the streets to offer up alternative ideals.

They chose to carve out room for themselves and their opinions in the public sphere, rather than fall victim to gaining airtime in often biased media outlets, the vast majority of which are either owned by, or affiliated with, the main political blocks.

Hamed Sinno, the lead singer of hit rock group Mashrou’ Leila and one of Lebanon’s only openly gay celebrities, has also dabbled in stencil artistry.

“The messages out there in the media were so aggressive towards homosexuality. There were no public platforms to fight this sort of thing so you go to a public platform – like a wall,” he said, while explaining what first inspired him to start stencilling public spaces.

It’s out of this fear that one of their few and most treasured ways of expression would be taken away that the artistic community and civil society banded together so quickly and with such force.

“I can write anything [on walls] and no one can do anything about it. It’s mine, my freedom of expression, and no one can tell me what to write,” said Omar Kabbani, one half of the Ashekman whose mural was erased

“I consider graffiti to be the real 8 o’clock news we have the news on the walls 24 hours a day.”

"Graffiti is meant to be removed. The whole issue here is that they removed a piece with a social and political message (freedom of expression) and we had all the permits to do it. As a graffiti artist, of course i get p***ed off if they remove any piece, but this will give us the motive to paint more."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].