War on Gaza: Refugee camps and the Palestinian psyche

What is a home in Gaza?

"For example, when I say Israel targeted a home, what’s a home? A home in America, in the UK; two people, a couple, a kid, a dog? But in Gaza, a home is a generational building." - Refaat Alareer, 13 October 2023.

Refaat, like so many other bright and unique spirits, departed us without having the chance to bid farewell, because the Israeli genocidal war on Gaza does not allow for loved ones to give a last embrace.

Yet, there was one, albeit forced, farewell more than 80 percent of Gaza's inhabitants were able to bid, and that was the farewell to their homes.

This was not the first time Palestinians have had to bid farewell to their homes and will not be the last, as long as an Israeli occupation remains and Palestine refugees are denied their self-determination and right of return.

But what exactly is this Palestinian "home" Refaat talked about?

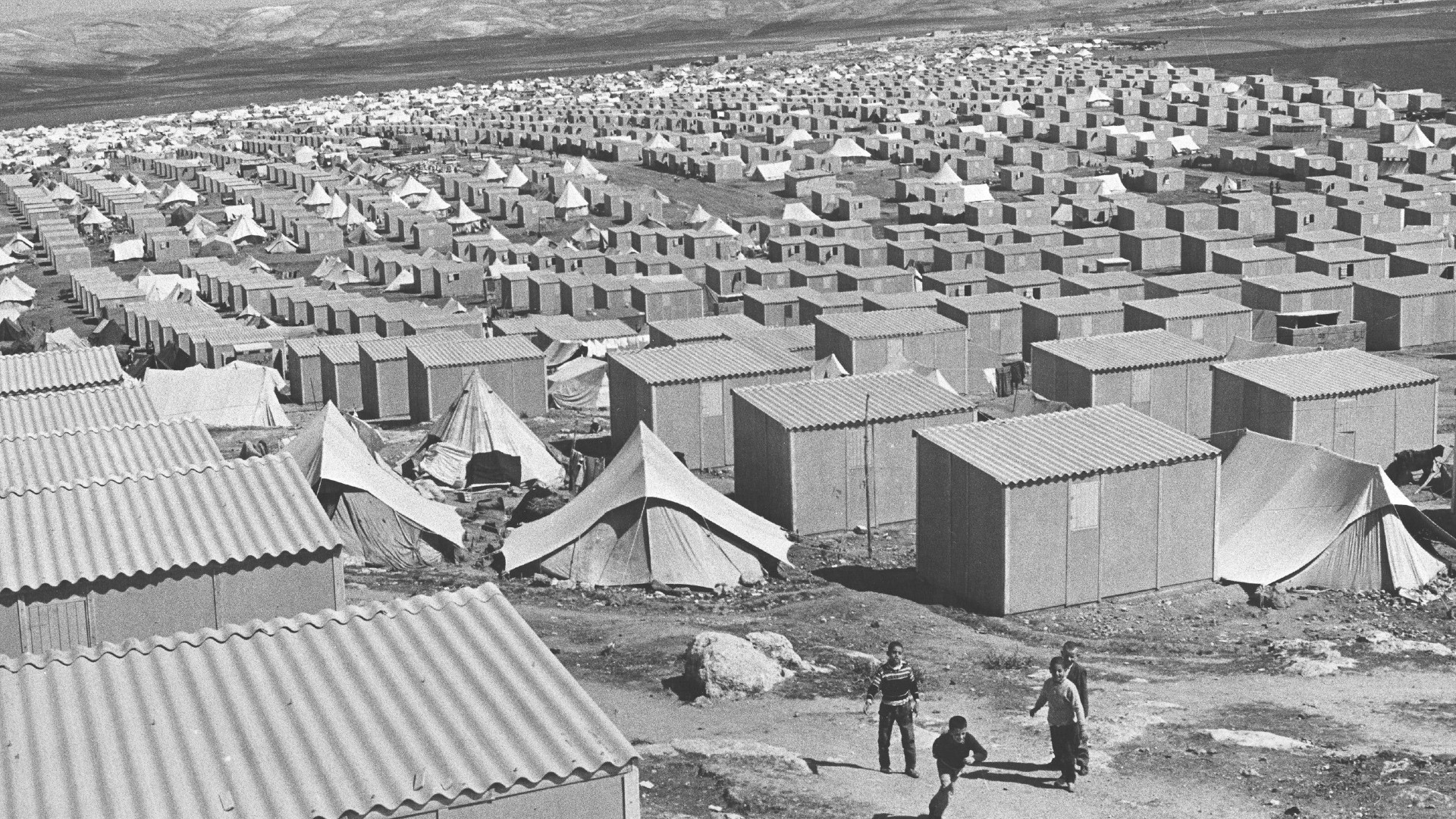

What Refaat was referring to was a 12 sqm room made of prefabricated material with a zinc roof, given to Palestine refugees after they had endured tents when they were forcibly displaced from their homeland in 1948 and 1967 respectively.

This room was provided for each refugee family on a 100 sqm plot of land in all Palestine refugee camps across the near east, with the camps left to grow independently as space and people inside a bordered piece of land deemed politically temporary. More specifically, what Refaat was referring to was the Palestinian shelter in the Palestine refugee camp.

Politically abandoned

Today, more than 1.5 million people live in 58 recognised Palestinian camps across Gaza, the West Bank, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon.

In Gaza alone, 80 percent of its 2.1 million population are refugees, half of whom still inhabit refugee camps. A dedicated UN agency, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (Unrwa), was established in 1949 to service Palestinian camps and refugees while maintaining a temporary status, regardless of how long these refugees would have to inhabit these camps.

Follow Middle East Eye's live coverage of the Israel-Palestine war

Furthermore, unlike its sister agency, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, which attends to all other refugees of the world, Unrwa is denied a political mandate to take an active role in repatriating Palestine refugees to their homeland.

This political paralysis was reinforced through downsizing the political urgency of the UN General Assembly-adopted "right of return" as exemplified in the proceeding resolutions.

The original text of article 11 in resolution 194 (III) adopted in December 1948, maintained that the General Assembly: "Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the governments or authorities responsible."

Apart from the problematic and contradictory wording of article 11 - whereby Palestinian refugees are portrayed as the ones interrupting peaceful coexistence while simultaneously recognising the "loss" and "damage" of Palestine property - the legal operative wording of the article changes dramatically.

Operative paragraphs inside UN resolutions begin with an action verb that expresses the action the UN member states agree on taking. The original action verb adopted for the "right of return" was "Resolves". "Resolves" proceeded to change into "Recognises" to "Considers" and then to "Endorses", effectively scaling down the responsibility of the international community towards the Palestinian displacement and its resolution.

This meant that Palestine refugees were politically abandoned and left to "carve into the rocks"- to use the Arabic proverb to mean trying to do the impossible - inside their camps as one camp leader put it to me in 2014. Indeed, Palestine refugees resorted to "carving into the rock", although it was cement that they carved instead of rock.

'Security threat'

Historically, refugee camps are designed with a purpose. That purpose could be to cut off solidarity across a society by creating a confinement embodied in a camp border; to develop and enrich impoverished rural zones; to concentrate and exterminate; or to quell the crisis at hand through resettlement and economic integration.

Yet, in all these mentioned examples, those sent to camps create their own agency and resist the sovereign's vicious aims, utilising whatever means their camps provide them with. In the Palestinian case, it was space and space-making. Palestinian refugees realised their inevitable protraction early on and that their fate is tightly connected to the camp as a space of refuge and a space of armed struggle to achieve self-determination.

In light of the international abandonment of the Palestinian ambition for return and self-determination, the Palestine refugees turned to their camps and shelters to compensate for the former. They worked hard to earn the means that would enable them to build space and livelihoods inside what is a controlled and confined space.

Palestine camps were meant to become economically and spatially integrated rather than sites of Palestinianhood and resistance. As a result, the camp became a "security threat" for the governments hosting them.

For the host governments and the international community, these camps were designed in a spatial layout that would allow controlled growth while utilising spatial means to downsize the political crisis.

The genocidal war in Gaza is very much a war on Gaza's refugee camps. This is in great part because half of Gaza's inhabitants live in camps and many more in camp extensions

The camp layout would adhere to rules and standards agreed on by the UN and host governments that ensure the camps grow into gridded spaces of controlled livelihoods, allowing the host government to easily police the space as well as swiftly storm it to quell any political activity, such as simple solidarity demonstrations.

As Michel Foucault proclaimed: "A territory that is well-policed in terms of its obedience to the sovereign is a territory that has good spatial layout."

The genocidal war in Gaza is very much a war on Gaza's refugee camps. This is in great part because half of Gaza's inhabitants live in camps and many more in camp extensions.

Furthermore, camps have historically been sites of active resistance against violent attacks and refugee refusal to give up their rights to self-determination. Enduring over 75 years of protracted displacement within confined spatial borders, the Palestine refugees built up their camps into densities that surpass that of Manhattan.

This enabled refugees to turn them into sites of innovative spatial resistance, utilising spatial elements such as tunnels or elevated walkways as strategic counter-offensive mechanisms to avoid on-the-ground movement, which is most vulnerable when the battle is confined to the camp.

As a result, the Israeli occupation army would build mock-ups of camps and Arab towns to train their soldiers on ways to innovatively attack such spatiality and density

Place of life and death

For Palestine refugees, their camps are spaces, places and means to resist occupation and violent oppression; to resist their exclusion from the professional workforce (as in Lebanon); to resist their social and economic marginalisation (as in Jordan and Syria); and to resist their controlled and forbidden movement (as in the occupied Palestinian territories).

While Palestinian camps grew in density and agency, host governments would adopt various spatial practices to re-exert control and confinement. For example, Jordan would adopt a spatial mode of reorganising the Palestine camp by widening camp streets that run in their middle, thus dividing them.

In Lebanon and the occupied territories it would be a mode of confinement, as in surrounding camps with cement walls and metal gates to control movement. In some cases, they would adopt a complete destruction of the camp, as in the cases of Tel Zaatar camp, Jisr el Basha camp, Nahr el Bared camp, Jenin camp, and today all of Gaza's camps.

So "what is a home" in a Palestinian camp? It is a place of refuge; a place of endurance; a place of livelihood; a place of happiness and misery; a place of resilience and steadfastness; a place full of memories and aspirations; a place of moments and conversations; a place of collective struggle and resistance; a place of sheltering your neighbour when they don’t have a place; a place of life and death.

Most of all, a home in a Palestinian camp is a place to remain in place until a just, rightful return is achieved.

As eminent British-Palestinian surgeon and humanitarian Ghassan Abu Sitta said: "One of the things that I think really surprised me about this war is that the humiliation of becoming a refugee, that degradation that happens to the soul of becoming a refugee, was such a formative part of Palestinian modern identity that it is a fate for Palestinians worse than death.

"That's why Jabalia camp is still full of people."

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].