How did the Ottoman caliphate come to an end?

It's 100 years since Turkey's Grand National Assembly abolished the 1,300-year old caliphate on 3 March 1924.

Its demise was a key moment in the history of the modern state which now has a population of more than 85 million and the 19th largest economy in the world.

But it was also a landmark in Islam's political history, and set the seal on the end of Ottoman rule, which shaped much of Europe, Africa and the Middle East for nearly six centuries.

The caliphate was an Islamic political institution that regarded itself as representing succession to the Prophet Muhammad and leadership of the world's Muslims.

It was never uncontested: at times multiple rival Muslim rulers simultaneously laid claim to the title of caliph.

Several caliphates have been declared throughout history, including the Abbasid caliphate of the ninth century, which dominated the Arabian peninsula as well as modern-day Iran, Iraq and Afghanistan; the 10th century Fatimid caliphate in modern Tunisia; and various caliphates centred on Egypt from the 13th century onwards.

How did the Ottoman caliphate come to exist?

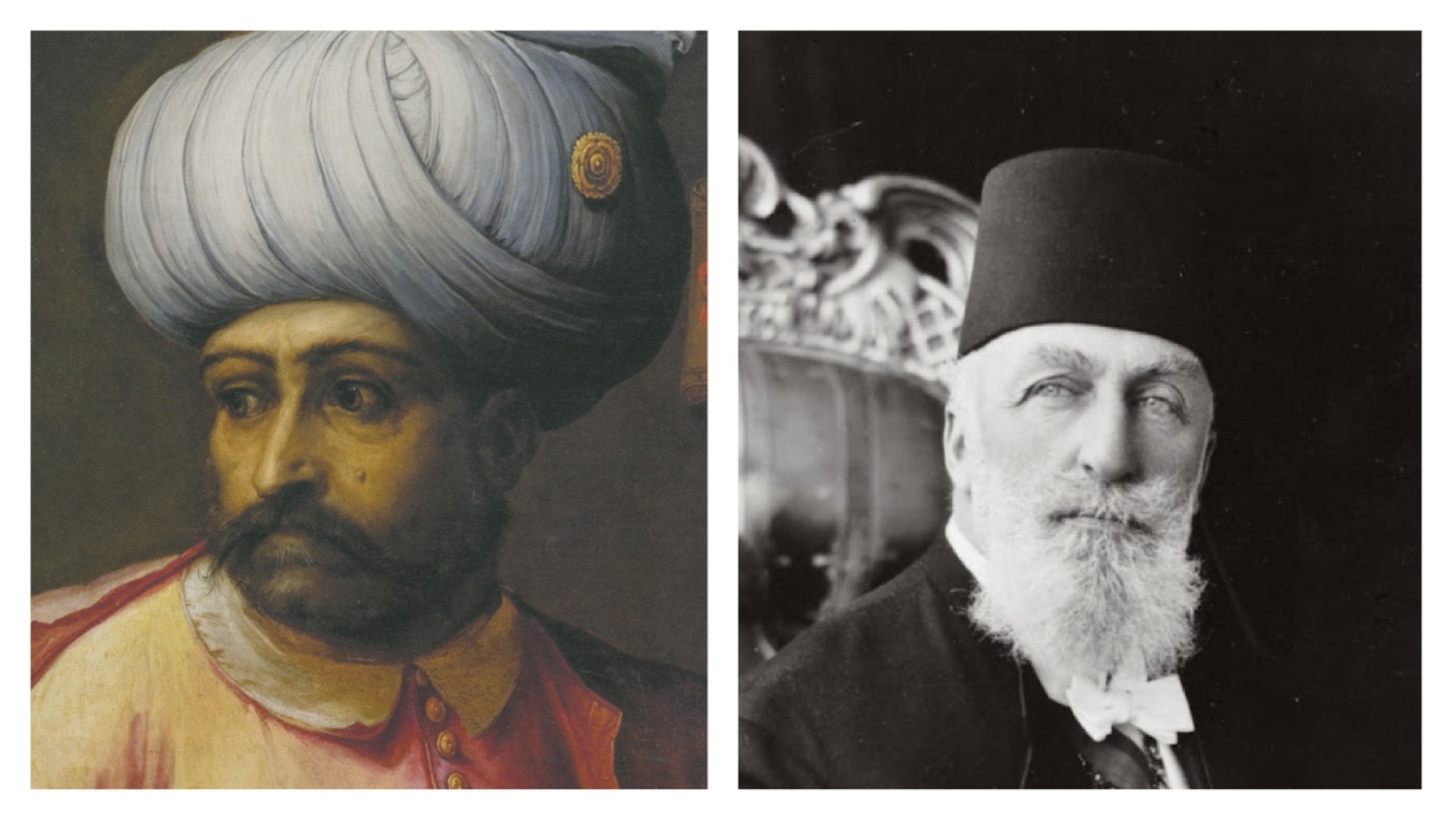

In 1512 the House of Osman, the ruling Ottoman dynasty, laid claim to the caliphate - a claim which grew stronger over the following decades, as the Ottoman empire conquered the Islamic holy cities of Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem, and Baghdad, the former capital of the medieval Abbasid caliphate, in 1534.

In recent years, historians have challenged the previously popular notion that the Ottomans paid little attention to the idea of the caliphate until the 19th century.

During the 16th century, the idea of the caliphate was radically reimagined by Sufi orders close to the Ottoman dynasty. The caliph was now a mystical figure, divinely appointed and endowed with both temporal and spiritual authority over his subjects. Thus the imperial court came to present the caliph (who was always the sultan) as no less than God's deputy on earth.

The Ottoman caliphate, whose nature was reinterpreted multiple times throughout the empire's history, was to survive for 412 years, from 1512 until 1924.

Who was the last caliph?

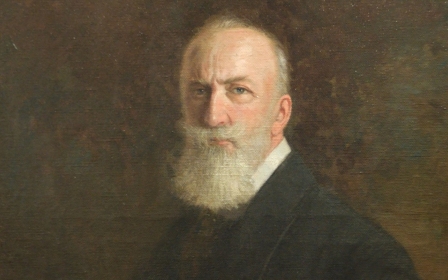

Prince Abdulmecid, who was born in 1868, spent much of his adult life under the heavy surveillance and relative confinement that the then-sultan, Abdulhamid II, imposed on the dynasty's princes.

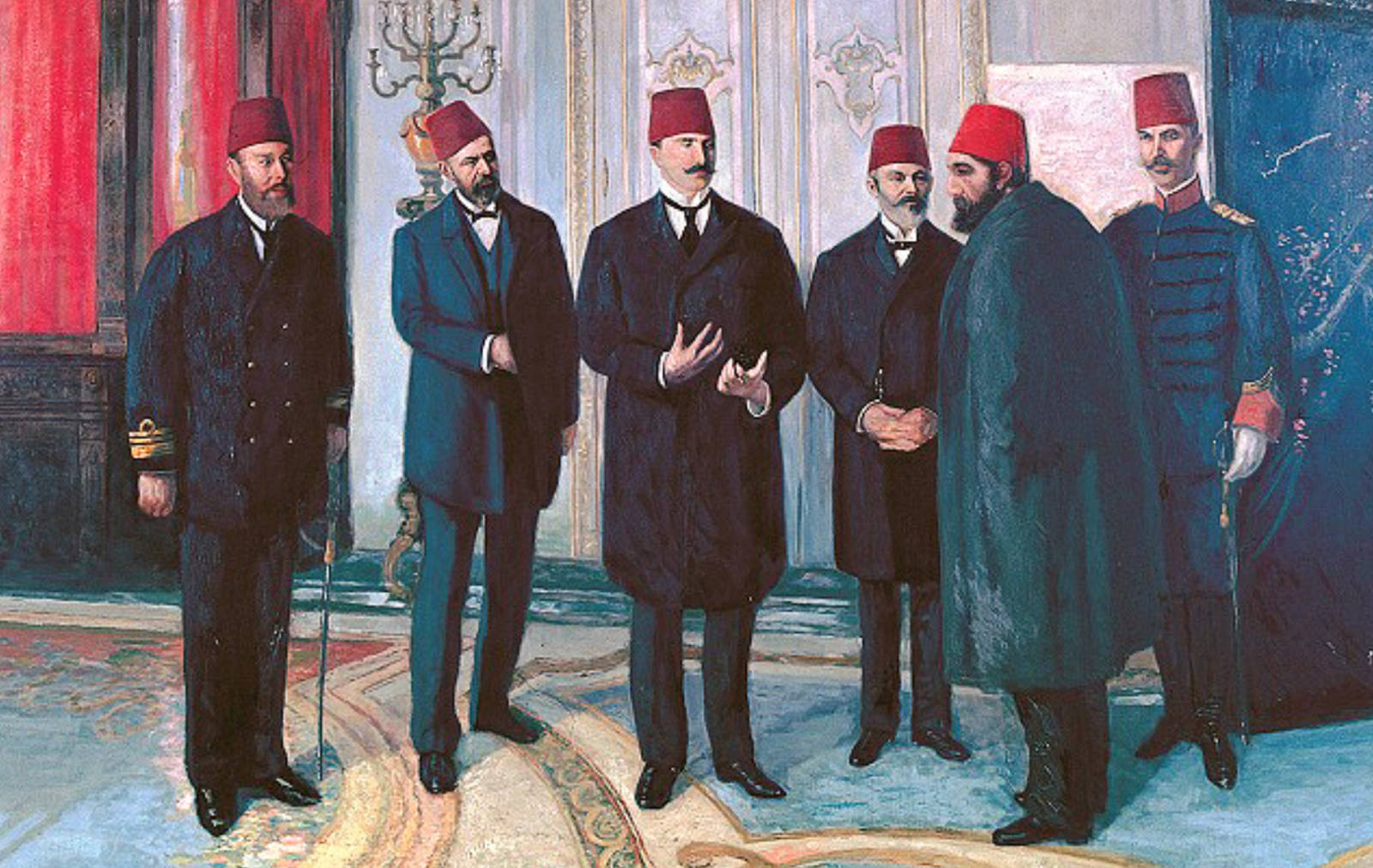

After Abdulhamid was deposed in a coup in 1909 and a "constitutional caliphate" introduced, Abdulmecid - a talented painter, a budding poet and a classical music enthusiast - became a fashionable public figure, styling himself as the "democrat prince". Not only did he produce a painting of Abdulhamid being removed from power, Abdulmecid even posed for a photo with the men who carried out the act.

But the prince was reduced to despair during the First World War (1914-1918) by the empire's military defeats; he was even more despondent during the resulting Allied occupation of Ottoman territory, including its capital Istanbul.

Mehmed Vahideddin was now sultan-caliph, with Abdulmecid crown prince, making him next in line to the throne. But in 1919 Vahideddin refused to support Mustafa Kemal Pasha's emerging nationalist movement as it fought against the Allied forces in Anatolia.

The nationalists established the Grand National Assembly in Ankara on 23 April 1920 as the foundation of a new political order. Later that year, Mustafa Kemal invited Abdulmecid to Anatolia to join the nationalist struggle.

But the Dolmabahce Palace in Istanbul, where the prince lived, was besieged by British soldiers. Abdulmecid had no choice but to decline the offer - a perceived slight that the republicans would later invoke when the tide turned against the caliphate.

How did Abdulmecid become caliph?

In October 1922, an armistice left the nationalists victorious and paved the way for the creation of modern Turkey. Sultan Vahideddin was widely reviled by his people. On 1 November the new government abolished the sultanate – and with it the Ottoman empire.

Vahideddin made an ignominious departure from Istanbul onboard a British battleship on 17 November. In his absence, the government deposed him from the caliphate, and instead offered the title of caliph to Abdulmecid, who immediately accepted and ascended on 24 November 1922.

For the first time, an Ottoman prince was to be made caliph but not sultan, and elected into the role by the Grand National Assembly.

How were relations between Ankara and Istanbul?

The conflict began almost immediately. In his new role, Abdulmecid was banned from making political statements: instead, the government in Ankara put forth a new vision of Islam in which the caliph was a mere figurehead. But as his granddaughter Princess Neslishah later wrote, Abdulmecid "had no intention of abiding by the given guidelines".

The New York Times informed its readers in April 1923 that the caliph, "a monogamous landscape painter, doesn't seem likely to cause anybody discomfort by his political pretensions".

This was in stark contrast to the reality in Turkey, where the grandeur and popularity of Abdulmecid's weekly processions to different mosques in Istanbul for the Friday prayer were increasingly perturbing Ankara. On one occasion, the caliph arrived at a mosque by crossing the Bosphorus on a 14-oared barge, exuberantly decorated with paintings of flowers and flying the caliphal standard.

Abdulmecid was no silent puppet-caliph: in contrast he threw banquets, established a "Caliphate Orchestra" and, much to Ankara's consternation, hosted political meetings in his palace.

What happened next?

After the liberation of Istanbul, Turkey was declared a republic on 29 October 1923. John Finley, an American who observed the Grand National Assembly in session, declared enthusiastically that the nation was "taking her first hopeful face-to-face view of the world".

He thought that the "interested and hopeful - and I think I may add, the beautiful - face of Latife Hanim [President Mustafa Kemal's wife]" could not be more different to the "stooped Caliph, whose grey hair was covered by a tassled fez". For many observers the two figures embodied contrasting aspects of Turkey: the future and the past.

One flashpoint was the government's furious reaction to a letter written by Muslim leaders in India to the Turkish prime minister on 24 November 1923. They warned that "any diminution in the prestige of the Caliph or the elimination of the Caliphate as a religious factor from the Turkish body politic would mean the disintegration of Islam and its practical disappearance as a moral force in the world".

The letter was published by three newspapers in Istanbul. Their editors were arrested, charged with high treason, and questioned in highly publicised tribunals before being released with their newspapers suppressed.

Increasingly, government officials saw Abdulmecid's caliphate as a serious threat to the republic's coherence. When US President Woodrow Wilson died in February 1924, Ankara refused to lower the flags on government buildings, since it had no diplomatic relations with Washington. But in Istanbul, the caliph ordered the Turkish flags on his palace and yacht to be lowered.

How did the tension eventually resolve itself?

By early 1924, the government had decided to abolish the caliphate.

Major newspapers began publishing articles attacking the Ottoman imperial family. If, on Friday 29 February, Abdulmecid was dismayed when his weekly procession was attended by more American tourists than Muslim faithful, he did not show it. Instead, he kept up appearances, greeting the crowd with dignity. But privately, he knew his position was untenable.

On Monday 3 March, the Grand National Assembly not only abolished the caliphate but stripped every member of the imperial family of their Turkish citizenship, sent them into exile, confiscated their palaces, and ordered them to liquidate their private property within a year.

Debate raged in the Assembly for more than seven hours. "If other Muslims have shown sympathy for us," Prime Minister Ismet Pasha proclaimed before the Assembly to widespread approval, "this was not because we had the Caliph, but because we have been strong". His argument eventually won out.

How was Abdulmecid deposed?

Haydar Bey, the governor of Istanbul, accompanied by Istanbul's Chief of Police, Sadeddin Bey, delivered the news to Abdulmecid just before midnight on 3 March.

They found the caliph studying the Qur'an in his library and read him the expulsion order. "I am not a traitor," Abdulmecid responded. "Under no circumstance will I go."

He then turned to his brother-in-law Damad Sherif: "Pasha, Pasha, we have to do something! You do something too!" But the pasha had nothing to offer his caliph. "My ship is leaving, sir," he replied, before bowing and quickly departing.

The caliph's daughter Princess Durrushehvar was 10 years old at the time. Her recollections of the night convey a feeling of betrayal not primarily by the government but by Turkey's people. "My father, whose family had been ruling for the past seven centuries, had sacrificed his life and his happiness for the people who no longer appreciated him," she said.

At around 5am, Abdulmecid emerged from the palace with his three wives, son, daughter and their senior housemaids. The deposed caliph was solemnly saluted by the soldiers and police who by now were surrounding the Dolmabahce.

Then he headed for Catalca, west of Istanbul. Waiting for the train, the family was looked after by a Jewish stationmaster who told them the House of Osman was "the benefactor of the Jewish people", and that to be able to serve the family "during these difficult times is merely the evidence of our gratitude". His words brought tears to Abdulmecid's eyes.

Back in Istanbul, the imperial princes were given two days to leave and 1,000 Turkish lira each; the princesses and other family members had just over a week to arrange their departure. When the princes left the city, a crowd "looking downcast and subdued" gathered to see them off.

Within days Abdulmecid's family had relocated to Territet, a picturesque suburb on Lake Leman in Switzerland.

What was the reaction of Turkey's new rulers?

Back in Ankara, the end of the caliphate was hailed as the beginning of a new era. Kemal, aiming to assuage global Muslim discontent, issued a statement announcing that the authority of the caliphate had been legitimately transferred to Turkey's Grand National Assembly.

But what was to come was a new secular order. In 1928 the Assembly even passed a bill removing all references to Islam in Turkey's constitution. Henceforth deputies were to swear "on honour" and not "before God".

Outside Turkey, the caliphate's abolition sparked a contest on who would assume the institution. Speculation abounded in the global press that a new caliphate would be launched from Mecca by King Hussein of the Hejaz. Egypt's King Fuad toyed with the idea of taking the role and the Emir of Afghanistan publicly put himself forward as a candidate. But no one could muster enough support from the Islamic world to credibly claim the title.

A week into his exile Abdulmecid issued a public proclamation from his Swiss hotel, arguing that "it is now for the Mussulman [Muslim] world alone, which has the exclusive right, to pass with full authority and in complete liberty upon this vital question."

His comments suggested a modern reworking of the Ottoman caliphate, in which it would depend not on the Ottoman empire for its legitimacy but instead the support of the world's Muslims.

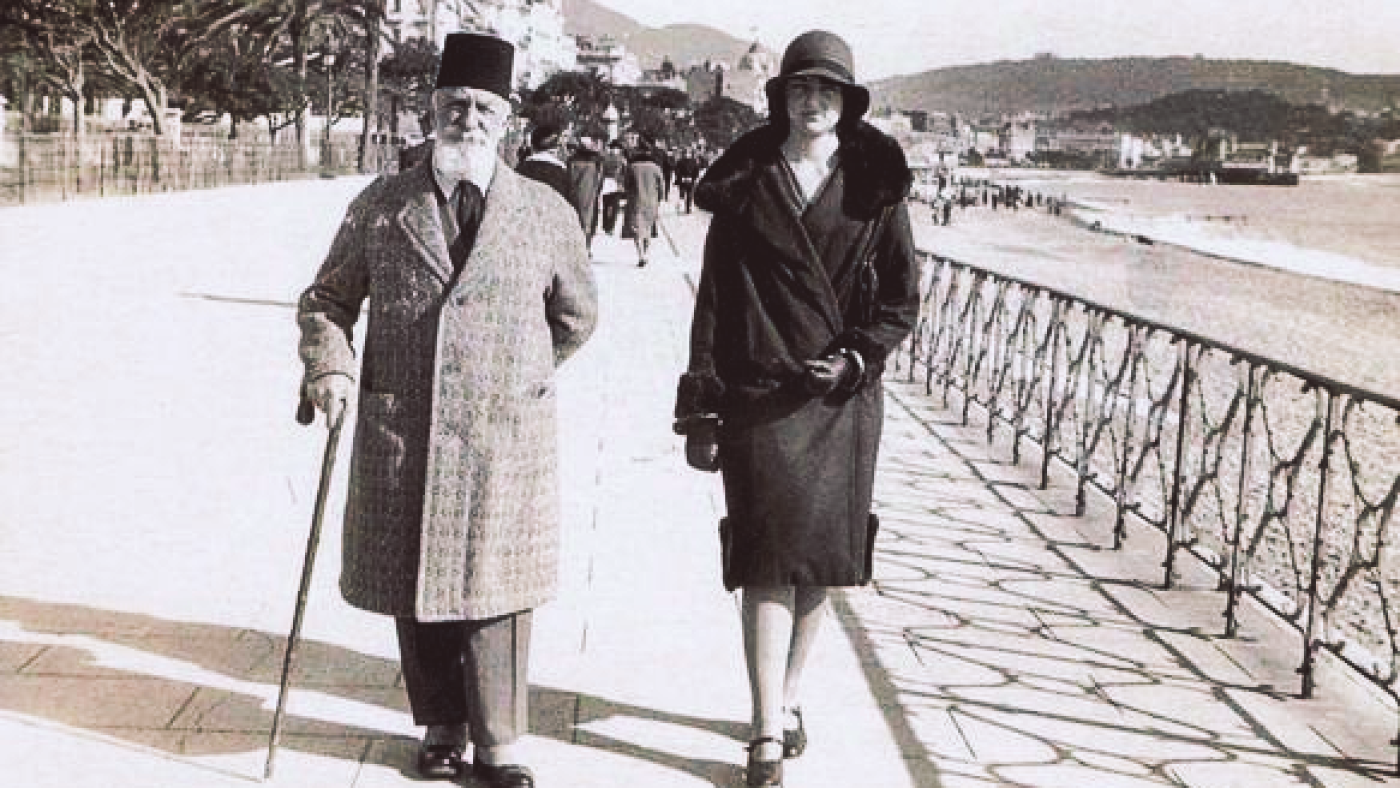

But such a plan would need powerful backing. The caliphal family ended up in a villa on the French Riviera, paid for by the nizam of Hyderabad, one of the world's richest men and ruler of a wealthy and modernising princely state in the Indian subcontinent.

It was to Hyderabad, and through a union of the House of Osman with the princely state's Asaf Jahi dynasty, that Abdulmecid looked for a revived caliphate. In 1931, Indian politician Shaukat Ali brokered a marriage between the caliph's daughter, Princess Durrushehvar, and the Nizam's eldest son, Prince Azam Jah.

Abdulmecid appointed their son - his grandson, who would be the future ruler of Hyderabad - as heir to the caliphate.

Ultimately, though, the caliphate was never declared - the newly formed republic of India annexed Hyderabad in 1948.

What happened to Abdulmecid?

The deposed caliph was never able to return to his beloved Istanbul. But in his years in exile, he never accepted the caliphate as abolished. Writing to a friend in July 1924, Abdulmecid described himself, quoting Shakespeare's Hamlet, as suffering the "slings and arrows of outrageous fortune" – though, unlike the Danish prince, he was still "hearty, with a clear conscience, a strong faith".

Abdulmecid died on the evening of 23 August 1944 in a villa near Paris, at the age of 76. US troops, trying to liberate France, were fighting the Germans nearby: when stray bullets flew into the villa, he suffered a heart attack.

In 1939 Abdulmecid had expressed his wish to be buried in India. The nizam had built a tomb for him, but by 1944 bringing the body over was considered politically untenable. The Turkish government, meanwhile, adamantly refused to allow a burial in Istanbul, and so Abdulmecid was interred in Paris for nearly a decade.

Finally, on 30 March 1954, the last caliph of Islam was buried in the Jannat al-Baqi graveyard in Medina, a site of pilgrimage, in Saudi Arabia; close by where the relatives and companions of the Prophet Muhammad lay.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].