Washington fights fire with fire in Libya

Is the US secretly training Libyan militiamen in the Canary Islands? And if not, are they planning to?

That’s what I asked a spokesman for US Africa Command (AFRICOM). “I am surprised by your mentioning the Canary Islands,” he responded by email. “I have not heard this before, and wonder where you heard this.”

As it happens, mention of this shadowy mission on the Spanish archipelago off the northwest coast of Africa was revealed in an official briefing prepared for AFRICOM chief General David Rodriguez in the fall of 2013. In the months since, the plan may have been permanently shelved in favor of a training mission carried out entirely in Bulgaria. The document nonetheless highlights the US military’s penchant for simple solutions to complex problems — with a well-documented potential for blowback in Africa and beyond. It also raises serious questions about the recurring methods employed by the US to stop the violence its actions helped spark in the first place.

Ever since the US helped oust dictator Muammar Gaddafi, with air and missile strikes against regime targets and major logistical and surveillance support to coalition partners, Libya has been sliding into increasing chaos. Militias, some of them jihadist, have sprung up across the country, carving out fiefdoms while carrying out increasing numbers of assassinations and other types of attacks. The solution seized upon by the US and its allies in response to the devolving situation there: introduce yet another armed group into a country already rife with them.

The rise of the militias

After Gaddafi’s fall in 2011, a wide range of militias came to dominate Libya’s largest cities, filling a security vacuum left by the collapse of the old regime and providing a challenge to the new central government. In Benghazi alone, an array of these armed groups arose. And on September 11, 2012, that city, considered the cradle of the Libyan revolution, experienced attacks by members of the anti-Western Ansar al-Sharia, as well as other militias on the American mission and a nearby CIA facility. During those assaults, which killed Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans, local armed groups called on for help or which might have intervened to save lives reportedly stood aside.

Over the year that followed, the influence of the militias only continued to grow nationwide, as did the chaos that accompanied them. In late 2013, following deadly attacks on civilians, some of these forces were chased from Libyan cities by protesters and armed bands, ceding power to what the New York Times called “an even more fractious collection of armed groups, including militias representing tribal and clan allegiances that tear at the tenuous [Libyan] sense of common citizenship.” With the situation deteriorating, the humanitarian group Human Rights Watch documented dozens of assassinations of judges, prosecutors, and members of the state’s already weakened security forces by unidentified assailants.

The American solution to all of this violence: more armed men.

Fighting fire with fire

In November 2013, US Special Operations Command chief Admiral William McRaven told an audience at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library that the United States would aid Libya by training 5,000 to 7,000 conventional troops as well as counterterrorism forces there. “As we go forward to try and find a good way to build up the Libyan security forces so they are not run by militias, we are going to have to assume some risks,” he said.

Not long after, the Washington Post reported a request by recently ousted Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan that the US train his country’s security forces. In January, the Pentagon’s Defense Security Cooperation Agency, which coordinates sales and transfers of military equipment abroad, formally notified Congress of a Libyan request for a $600 million training package. Its goal: to create a 6,000 to 8,000-man “general purpose force,” or GPF.

The deal would, according to an official statement, involve “services for up to 8 years for training, facilities sustainment and improvements, personnel training and training equipment, 637 M4A4 carbines and small arms ammunition, US Government and contractor technical and logistics support services, Organizational Clothing and Individual Equipment (OCIE), and other related elements of logistical and program support.”

In addition to the GPF effort, thousands of Libya troops are to be trained by the militaries of Morocco, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and Italy. The Libyan Army also hopes to graduate 10,000 new troops at home annually.

While Admiral McRaven has emphasized the importance of building up “the Libyan security forces so they are not run by militias,” many recruits for the GPF will, in fact, be drawn from these very groups. It has also been widely reported that the new force will be trained at Novo Selo, a recently refurbished facility in Bulgaria.

The US has said little else of substance on the future force. “We are coordinating this training mission closely with our European partners and the U.N. Support Mission in Libya, who have also offered substantial security sector assistance to the Government of Libya,” a State Department official told TomDispatch by email. “We expect this training will begin in 2014 in Bulgaria and continue over a number of years.”

There have been no reports or confirmation of the plan to also train Libyan militiamen at a facility in Spain’s Canary Islands mentioned along with Novo Selo in that Fall 2013 briefing document prepared for AFRICOM chief Rodriguez, which was obtained by TomDispatch.

Officials at the State Department say that they know nothing about this part of the program. “I'm still looking into this, but my colleagues are not familiar with a Canary Islands component to this issue,” I was told by a State Department press officer. AFRICOM spokesman Benjamin Benson said much the same. “[W]e have no information regarding training of Libyan troops to be provided in the Canary Islands,” he emailed me. After I sent him the briefing slide that mentioned the mission, however, he had a different response. The Canary Islands training mission was, he wrote, part of an “initial concept” never actually shared with General Rodriguez, but instead “briefed to a few senior leaders in the Pentagon.”

“The information has been changed, numerous times, since the slide was drafted, and is expected to change further before any training commences,” he added, and warned me against relying on it. He did not, however, rule out the possibility that further changes might revive the Canary Islands option and demurred from answering further questions on the subject. A separate US Army Africa document does mention that “recon” of a second training site was slated to begin last December.

Neither the State Department nor AFRICOM explained why plans to conduct training in the Canary Islands were shelved or when that decision was made or by whom. Benson also failed to facilitate interviews with personnel involved in the Libyan GPF training effort or with top AFRICOM commanders. “Given the continuing developing nature of this effort, it would be inappropriate to comment further at this time, and we have not been giving interviews on the topic,” he told me. Multiple requests to the Libyan government for information on the locations of training sites also went unanswered.

Training day

Wherever the training takes place, the US has developed a four-phase process to “build a complete Libya security sector.” The Army’s 1st Infantry Division will serve as the “mission command element for the Libyan GPF training effort” as part of a State Department-led collaboration with the Department of Defense, according to official documents obtained by TomDispatch.

Agreements with partner nations are to be finalized and Libyans selected for leadership positions as part of an initial stage of the process. Then the US military will begin training not only the GPF troops, but a border security force and specialized counter-terror troops. (Recently, AFRICOM Commander David Rodriguez told the Senate Armed Services Committee that the US was also helping to build up what he termed Libyan “Special Operations Forces.”) A third phase of the program will involve developing the capacities of the Libyan ministries of justice, defense, and the interior, and strengthening Libya’s homegrown security training apparatus, before pulling back during a fourth phase that will focus on monitoring and sustaining the forces the US and its allies have trained.

Despite reports that training at Novo Selo will begin this spring, a State Department official told TomDispatch that detailed plans are still being finalized. After inspecting a briefing slide titled “Libya Security Sector Phasing,” AFRICOM’S Benson told me, “I do not see us in any phase as indicated on the slide… the planning and coordination is still ongoing.” Since then, Lolita Baldor of the Associated Press reported that, according to an unnamed Army official, a small team of US soldiers has now headed for Libya to make preparations for the Bulgarian portion of the training.

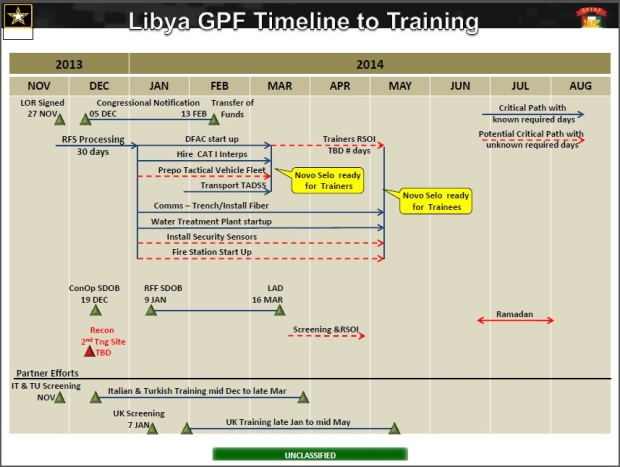

A timeline produced by US Army Africa as part of a December 2013 briefing indicates that the Novo Selo site would be ready for trainers sometime last month. After communications systems and security sensors are set up, that training range will be ready to accept its first Libyan recruits. The timeline suggests that this could occur by early May.

While this may have been an early version of the schedule, there’s little doubt the program will begin soon. Baldor notes that formal Libyan approval for the training may come this month, although AFRICOM Commander David Rodriguez pointed out at a Pentagon press briefing that the Libyan government still has to ante up the funds for the program, and a Libyan official confirmed to TomDispatch that the training had yet to commence.

Experts have, however, already expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of the program. In late 2013, for instance, Benjamin Nickels, the academic chair for transnational threats and counterterrorism at the Department of Defense’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies, raised a number of problematic issues. These included the challenge of screening and vetting applicants from existing Libyan militias, the difficulty of incorporating various regional and tribal groups into such a force without politicizing the trainee pool; and the daunting task of then devising a way to integrate the GPF into Libya’s existing military in a situation already verging on the chaotic.

“For all their seriousness,” wrote Nickels, “these implementation difficulties pale in comparison to more serious pitfalls haunting the GPF at a conceptual level. So far, plans for the GPF appear virtually unrelated to projects of disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) and security sector reform (SSR) that are vital to Libya’s future.”

Berny Sebe, an expert on North and West Africa at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, noted that, while incorporating militiamen into a “mainstream security system” could help diminish the power of existing militias, it posed serious dangers as well. “The drawback is, of course, that it can infiltrate factious elements into the very heart of the Libyan state apparatus, which could further undermine its power,” he told TomDispatch by email. “The use of force is unavoidable to enforce the rule of law, which is regularly under threat in Libya. However, all efforts placed in the development of a security force should go hand in hand with a clear political vision. Failure to do so might solve the problem temporarily, but will not bring long-term peace and stability.”

In November 2013, Frederic Wehrey, a senior associate with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and an expert on Libya, pointed out that the project seemed reasonable in the abstract, but that reality might be another matter entirely: “[T]he force’s composition, the details of its training, the extent to which Libyan civilians will oversee it, and its ability to deal with the range of threats that the country faces are all unclear.” He suggested that an underreported 2013 mission to train one Libyan unit that ended in abject failure should be viewed as a cautionary tale.

Last summer, a small contingent of US Special Operations Forces set up a training camp outside of Libya’s capital, Tripoli, for an elite 100-man Libyan counter-terror force whose recruits were personally chosen by former Prime Minister Ali Zeidan. While the Americans were holed up in their nighttime safe house, unidentified militia or “terrorist” forces twice raided the camp, guarded by the Libyan military, and looted large quantities of high-tech American equipment. Their haul included hundreds of weapons, Glock pistols and M4 rifles among them, as well as night-vision devices and specialized lasers that can only be seen with such equipment. As a result, the training effort was shut down and the abandoned camp was reportedly taken over by a militia.

This represented only the latest in a series of troubled US assistance and training efforts in the Greater Middle East and Africa. These include scandal-plagued endeavors in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as a program that produced an officer who led the coup that overthrew Mali’s elected government, and an eight-month training effort in the Democratic Republic of Congo by US Special Operations forces that yielded an elite commando battalion that took part in mass rapes and other atrocities, according to a United Nations report. And these are just the tip of the iceberg among many other sordid examples from around the world.

The answer?

The US may never train a single Libyan militiaman in the Canary Islands, but the plan to create yet one more armed group to inject into Libya’s already fractious sea of competing militias is going forward -- and is fraught with peril.

For more than half a year, a militia controlled the three largest ports in Libya. Other militiamen have killed unarmed protesters. Some have emptied whole towns of their residents. Others work with criminal gangs, smuggling drugs, carrying out kidnappings for ransom, and engaging in human trafficking. Still others have carried out arbitrary arrests, conducted torture, and been responsible for deaths in detention. Armed men have also murdered foreigners, targeted Christian migrants, and fought pro-government forces. Many have attacked other nascent state institutions. Last month, for instance, militiamen stormed the country's national assembly, forcing its relocation to a hotel. (That assault was apparently triggered by a separate unidentified group, which attacked an anti-parliament sit-in, kidnapping some of the protesters.)

Some militias have quasi-official status or are beholden to individual parliamentarians. Others are paid by and support the rickety Libyan government. That government is also reportedly engaging in widespread abuses, including detentions without due process and prosecutions to stifle free speech, while failing to repeal Gaddafi-era laws that, as Human Rights Watch has noted, “prescribe corporal punishment, including lashing for extramarital intercourse and slander, and amputation of limbs.”

Most experts agree that Libya needs assistance in strengthening its central government and the rule of law. “Unless the international community focuses on the need for urgent assistance to the justice and security systems, Libya risks the collapse of its already weak state institutions and further deterioration of human rights in the country,” Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch, said recently. How to go about this remains, however, at best unclear.

“Our Defense Department colleagues plan to train 5,000 to 8,000 general purpose forces,” Anne Patterson, the assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern Affairs, told the House Armed Services Committee earlier this year, noting that the US would “conduct an unprecedented vetting and screening of trainees that participate in the program.” But Admiral William McRaven, her "Defense Department colleague," has already admitted that some of the troops to be trained will likely not have “the most clean record.”

In the wake of failed full-scale conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the US military has embraced a light-footprint model of warfare, emphasizing drone technology, Special Operations forces, and above all the training of proxy troops to fight battles for America’s national security interests from Mali to Syria — and soon enough, Libya as well.

There are, of course, no easy answers. As Berny Sebe notes, the United States “is among the few countries in the world which have the resources necessary to undertake such a gigantic task as training the new security force of a country on the brink of civil war like Libya.” Yet the US has repeatedly suffered from poor intelligence, an inability to deal effectively with the local and regional dynamics involved in operations in the Middle East and North Africa, and massive doses of wishful thinking and poor planning. “It is indeed a dangerous decision,” Sebe observes, “which may add further confusion to an already volatile situation.”

A failure to imagine the consequences of the last major US intervention in Libya has, perhaps irreparably, fractured the country and sent it into a spiral of violence leading to the deaths of Americans, among others, while helping to destabilize neighboring nations, enhance the reach of local terror groups, and aid in the proliferation of weapons that have fueled existing regional conflicts. Even Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for African Affairs Amanda Dory admitted at a recent Pentagon press briefing that the fallout from ousting Gaddafi has been “worse than would have been anticipated at the time.” Perhaps it should be sobering as well that the initial smaller scale effort to help strengthen Libyan security forces was an abject failure that ended up enhancing, not diminishing, the power of the militias.

There may be no nation that can get things entirely right when it comes to Libya but one nation has shown an unnerving ability to get things wrong. Whether outside of Tripoli, in Bulgaria, the Canary Islands, or elsewhere, should that country really be the one in charge of the delicate process of building a cohesive security force to combat violent, fractious armed groups? Should it really be creating a separate force, trained far from home by foreigners, and drawn from the very militias that have destabilized Libya in the first place?

- Nick Turse is the managing editor of TomDispatch and a fellow at the Nation Institute. A 2014 Izzy Award winner, his pieces have appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Nation, at the BBC, and regularly at TomDispatch. He is the author most recently of the New York Times bestseller Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam (now in paperback).

Copyright 2014 Nick Turse (republished from TomDispatch with permission)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].