Suspected ‘price tag’ attack in Jerusalem leaves community shaken

Sunday was a peaceful day on Mount Zion, the hill outside the northwest wall of Jerusalem’s Old City. Tourists mingled with the religious Jews and Christians that both have holy buildings here, and the early spring sunshine made the streets warm and bright. The quiet, however, was misleading.

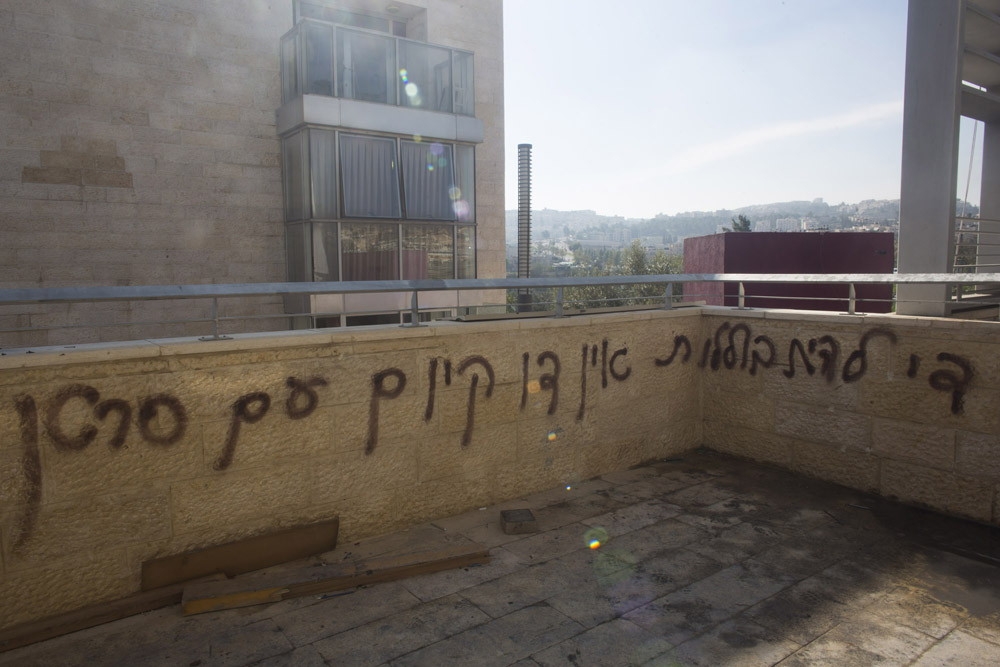

Last Thursday at dawn, masked men invaded the courtyard of a Christian seminary, setting fire to a bathroom and starting a fierce blaze metres from where students of the school were sleeping. Graffiti the attackers left on the building - insulting Jesus and the Virgin Mary, and stating “Zion will come”- indicated that they were Jewish extremists.

Andreas, a 17-year-old student at the seminary who preferred not to use his real name, described the attack to Middle East Eye.

“They broke the window and threw gasoline inside, which burned all the area,” he said. “The police came and they saw the fire. They rang the bell, because everyone was sleeping inside.

“I answered the bell and opened the door. As I walked down the corridor I couldn’t see in front of me because it was filled with smoke.”

Residents said that cameras attached to the buildings caught footage of the perpetrators of the attack, who appeared to be young – 16 or 17 years old and who were wearing masks to conceal their identities.

The first, which took place on Wednesday morning, targeted a mosque in the West Bank village of al-Jaba’a. It too involved arson and graffiti: vandals set fire to the building, causing damage to the walls and carpet, and left graffiti reading “we want the redemption of Zion”, “revenge” and with a star of David on its walls. In a third incident, “death to Arabs” was sprayed on the walls of a school near Nablus.

An international observer working with the Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI) said settler violence of this nature is far from unusual, and that mosques and other public buildings were often a target.

“I think people here are very, very afraid. They fear that they will be coming back,” she told MEE over the phone. “People are most scared that they will threaten their kids, perhaps at school, and hurt people, not just property.”

A familiar pattern

All last week’s incidents fit a familiar pattern of anti-Palestinian violence perpetrated by extremist Israelis in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and even against Palestinian communities in Israel, where hundreds of people protested against a rash of extremist hate crimes in April last year. Attacks take the form of property damage and vandalism, such as spraying graffiti, slashing car tyres, or - in the more extreme cases - setting light to mosques and schools. Hundreds of these attacks take place every year.

Nader Hana, an advocacy officer for EAPPI, which sends international observers to document abuses perpetrated by settlers and the occupation, described settler violence as existing on a scale “from harassment through to vandalism, to violence”. Harassment, he told MEE, might include verbally abusing Palestinians in the streets of Hebron, vandalism the burning of olive trees or spraying graffiti, and physical violence assault that may even be life-threatening.

What is the motivation behind such incidents? While the fascist and often juvenile tone of the graffiti demonstrates that prejudice plays a key role, there may be a strategy behind these crimes too. Many media outlets dubbed last week’s incidents “price tag” attacks, a term for a particularly targeted kind of settler violence. Its perpetrators - generally extremist, right-wing Israelis, who often live in radical West Bank outposts - believe damage to Palestinian life or property is “repayment” for perceived injuries to the Israeli settler community.

In the past, spikes in attacks have followed crackdowns on illegal settlements, including the demolition of several structures in Yitzhar last spring. These extremists believe they are seeking what Haaretz writer, Amos Harel described as a “balance of terror” - a situation in which every move against the interests of settlers will be met with a violent action in return. The strategy, Harel argues, will force the Israeli government to think twice about issuing further orders against settlers.

Despite the assertions of many media outlets, however, at EAPPI Hana was reluctant to describe the recent attacks as price tag incidents.

“It’s hard to know what’s actually a price tag attack,” he told MEE. Only a few attacks by settlers are explicitly accompanied by price tag graffiti, which often clearly lays out that vandalism was repayment for actions taken by the government against Israelis. “I’m not entirely sure the recent incidents were price tag attacks,” Hana explained. “I would categorise them as settler violence. Price tag attacks are a very unique kind of settler violence.”

The precise classification of these incidents, however, does not make them any less serious. In many cases, violence by settlers can be understood as an attempt to intimidate and harass local Palestinian populations into leaving land that expansionist Israelis want to occupy themselves. Sometimes, the strategy is effective, sometimes not: “I see some people who’ve just given up, and others who remain adamant,” Hana says.

At the seminary where Andreas studies, low-level harassment is a big problem too. Andreas told MEE that large groups of Israeli Jews throw stones, verbally abuse or gather threateningly around the building on a regular basis. During January, he says, a large group of “radical extremists” gathered in the garden of the seminary between 11pm and midnight and held a barbecue party there, playing loud music, ringing the bell of the building where students were sleeping, and refusing to leave.

“They are radical, they just represent a small number of Israeli people,” Andreas said. “They make a problem in the school, and in the whole of Mount Zion, because they want this place. They’re always here and there’s always problems, problems, problems.”

Is this a threat that Israeli authorities take seriously? In the case of recent attacks, officials certainly made a strong commitment to condemning violence and promising justice. Reuven Rivlin, Israel’s president, condemned the Jerusalem attack in no uncertain terms. “It is inconceivable that an act like this could happen in a house of prayer,” he was quoted as saying to Greek Orthodox Patriarch Theophilos III. “This is a heinous crime, there must be an investigation and those responsible must be brought to justice.”

Speaking on the phone to MEE, police spokesperson Micky Rosenfeld said that an investigation into the incident at the seminary was ongoing, and that there had been an increase in police operations in the West Bank as well as Jerusalem.

“Every incident that happens is very serious and taken very seriously, not just by the police themselves but by intelligence agencies too,” he said.

Inadequate response

The response to incidents like these, however, does appear to be plagued by a lack of success. Over a period of 18 months between 2012 and 2013, 788 cases of price tag attacks were reported across Israel and Palestine, according to the Israeli agency YNet, yet the incidents resulted in only 276 arrests and 154 indictments. And although such attacks are deemed “nationalistic crimes” and a top priority for authorities, the Israeli government has defied recommendations of the Shin Bet and declined to label price tag attacks acts of terror.

Whether or not the response has been adequate, Andreas said the police response to the seminary’s problem does make him feel safer. That, however, might be less to do with the strength of the official response, and more about the degree of fear the teenager feels in his Jerusalem home. “The police are very good,” he said on Sunday. “I think if it wasn’t for the police then I think I would be killed. I would be dead.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].