Syria: A traumatised nation

Many media outlets vie among themselves regarding the death toll from the Syrian conflict during the last four years. UN statistics conclude that this vile war’s fatalities sit in the region of 200,000. But one notes the near absence in mainstream media of a proper and thorough engagement with the human experiences of war beyond numbering the deaths, or beyond directing the blame towards a certain armed group. Syrians’ tragedies of survival inside and outside Syria must be examined.

The Syrian Ministry of Health recently released a report about the abject lack of coping in the mental health sector in the country. This report was not picked up by mainstream media in the West. The Ministry told al-Watan newspaper that 40 percent of Syrians urgently need mental health support, and 15 percent of those who suffer severe depression contemplate suicide.

Those hit hardest by mental health problems are the young and children, the ministry added, and the unchecked expansion of war across the country exacerbates the problem. Modest health facilities in the country cannot offer proper services to mental health patients.

The Syrian government’s narrative about mental health is absolutely accurate, as my friends in the health sector keep informing me about the unprecedented level of trauma they encounter among patients. But the government gets it wrong when it makes no comment about the poor care in mental health facilities in the main cities in Syria even before the revolution started.

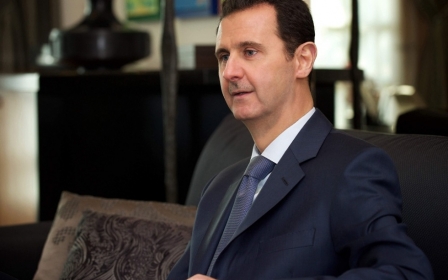

Furthermore, the government gets it wrong when it fails to mention how its own machinery of war performs magic in exterminating people and pushes many among those who manage to avoid the long hand of death further towards the grip of depression and suicide. In the latest interview with the BBC, President Bashar al-Assad had only his army’s "heroic" deeds in the fight against the opposition and Daesh (the Islamic State group) to talk about. Assad did not mention how the living Syrians, inside and outside the country, are managing the traumatic experiences of living in a country drenched in war and blood.

But how do Syrians handle the trauma of dispossession, war and loss on a daily basis?

Trauma and survival

The tragedy of war in Syria is absolutely irrational. In the last four years, ordinary citizens in the country have been trying to grasp why this tragedy cannot be brought to an end. “So far they have failed to do so,” Dr Ramia, a health worker in one of the remaining functional hospitals in Damascus told me. “Many of those who found it impossible to cope with the absurdity of war have fallen into depression and some have already committed suicide,” Dr Ramia added.

But many of those who could not avoid living under the rage of war have been successful in developing tactics of survival based on what we sometimes call indifference or disenchantment. “We are a traumatised nation,” George, a primary school teacher from Damascus, a friend of mine, once said. “Nevertheless, we do not care about the agendas of the warring parties. We just want to live,” he added.

When I asked him how they manage to survive in these difficult moments and whether the war continues to push their mental health conditions towards the edge, he answered that it does, but that they have many things to do in their life that allow them to forget or pretend to forget the absurdity of war. There are games such as cards, football and also chess, he mentioned. There are also the coffeehouse’s gossips and jokes. When I asked about the kind of jokes people use these days in Damascus, he mentioned these daft topics: death, bullets, religious extremism and sectarianism.

I asked for a joke. He replied: "Once a group of friends met in a coffee house to play chess. A man, a friend, approached them and began to say how the government would soon work on fixing severe power and electricity shortages in Damascus. People pretended not to listen to him. They have now become skilful in using the technique of disenchantment or, to put it quite sarcastically, the “stiff upper lip”. They did not believe that what he said was true. They ignored him. But when he mentioned how their previous neighbour, Salim, who lived around the corner had recently died during the government’s raids on the suburbs of the capital, people believed him. They even offered him a chair to sit and also a free cup of tea." This sad story is a clear expression of how traumatised Syrians have become. For my friend George, it is a funny story. I recall that he couldn't stop laughing when he told it to me.

Trauma and heroism

Last November, Pope Francis used the word “cemetery” to describe the tragedy facing many Syrian refugees crossing the Mediterranean to Europe. The use of the word “cemetery” here is deeply profound. If Syrians have become determined to end up braving a cemetery to reach the shores of Europe, then what kind of space did they inhabit before setting out to reach Europe? Is living in Syria worse than ending up in a cemetery, or is life in a cemetery better than living in Syria?

For many Syrians that I spoke with, the debate about the Syrian tragedy across the dangerous seas can be transformed into one of heroism. Many of those refugees who successfully braved the Mediterranean cemetery tend to "unlearn" their tragic journeys by constructing themselves as heroes, not victims. “After all, who can jump into a shaky wooden boat from Turkey into Europe with prior knowledge that death is something we will encounter?”

This question was the reply of a Syrian refugee I met in Sweden. “We have shown the world that heroism is ours and only ours,” Raed said. It is my personal observation that the tactical survival that many Syrians have developed within the country has now in diaspora become a narration of heroism. I find it fascinating that when I confront many of the Syrians I meet about the psychological trauma of war, they respond by saying: “We make no apology that we are a nation embroiled in traumas. But things will not remain like that forever. The slow return of the smell of jasmine within the old walls of Damascus, inshallah, will dispel the smell of gunpowder."

Hearing this, I shuddered.

- Dr Mohammad Sakhnini is a writer and journalist based in London. He lived in Damascus before moving to the UK to do his MA and PhD in English literature at the University of Exeter. His articles have appeared in several academic journals and media outlets.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Syrians, inside and outside the country, are coping with the traumatic experiences of living in a country drenched in war and blood (AA)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].