France’s ‘Islam of the suburbs’ and the illusions of the media

In France the word “Islam” often invokes the term “suburb”[A word the French associate with an impoverished neighbourhood]. While it is widely used by both French politicians and the media, it encompasses realities more complex than they appear. Between religious fervour and violent militancy, Islam in the French suburbs is an issue that governments are struggling to define.

Conflating suburbs and terrorism

In a session of the French Senate on 12 February 2015, Prime Minister Manuel Valls expressed concerns over “Salafist groups based in a number of our neighbourhoods” stressing “the influence of these groups in the Chechen circle of influence.”

Four days earlier, six people suspected of belonging to a militant cell were arrested near Toulouse and Albi in the south of France. The following day, in an interview with La Provence newspaper, Valls said it was a “Chechen network on their way to Syria.”

On 12 January, Nicolas Sarkozy, president of the main opposition party UMP, deplored how “immigration complicates things” regarding terrorism, pointing out in a statement to RTL radio “the difficulties of integration” and the resulting “communitarianism”.

Similarly, on 23 February, Roger Cukierman, president of France’s Jewish Institutions Representative Council (CRIF), went further by stating that “all the violence is committed by young Muslims”.

These comments, in the wake of the prime minister’s remarks, hint at the alleged links between Islam, the suburbs and terrorism.

On the ground

In 1991, Gilles Kepel, a French political scientist and professor of Sciences Po Paris, published a reference book on that matter: Les banlieues de l'islam: naissance d'une religion en France [The Suburbs of Islam: the Birth of a Religion in France]. Kepel, an expert on Islam, traced the religion’s development in France from 1926 to the 1990s when it began settling in the impoverished neighbourhoods.

Kepel distinguished three phases: the fathers’ Islam; the brothers’ Islam related to the migrants’ countries of origin; and the youth’s Islam. Kepel sought to prove how Islam in France has become an Islam of France.

Based on field research, Kepel unveils the reality of the Muslim community.

Twenty-five years later, Kepel, accompanied by five researchers, returned to the suburbs in order to observe what had changed, and especially to understand from an insider’s perspective how Islam has evolved.

The survey, titled “Suburbs of the Republic”, focused on a specific geographic area: Montfermeil and Clichy-sous-Bois in the Paris suburban city of Seine-Saint-Denis, where the 2005 riots began.

The research, published by a French think tank the Institut Montaigne, aimed to delve deeper than the Suburbs of Islam book:

“'Suburbs of the Republic' goes further into the inextricably interwoven layers where the Islam of France is evolving 25 years later: the habitat, in degraded - or renovated - suburbs and detached houses; school, college and high school; employment and unemployment; public tranquility and riots; civil society networks, local elections; mosque building, Ramadan, halal,” as one can read in the introduction.

The survey, with two-thirds of the respondents being Muslims, highlights “a skyrocketing increase of the halal market and the expansion of such a concept”. According to Kepel’s survey, the halal concept, which sets the boundary between the lawful and the unlawful in Islam, extends to various aspects of social life.

Another research finding is about the presence of the Tabligh movement (which means “spreading Islam”), a proselytising and pious movement that has mostly targeted suburban youth in order to “re-socialise” them through Islam.

The movement is not really welcomed by local representatives, as in the area of Lunel, in France’s southern department of Hérault. Last December, the city was shocked to discover that six of its young people were killed while fighting within the ranks of the Islamic State in Syria. “We are facing a phenomenon of sectarian deviation,” said Philippe Moissonnier, councillor of the Socialist Party (PS) in the city.

Islam by default?

According to Kepel’s survey, the socioeconomic malaise in the suburbs resulted in an increased devotion and religiosity.

Thus, with an unemployment rate of 22.7 percent in Clichy-sous-Bois against 11 percent in Ile-de-France [the Paris metropolitan area], the survey alleges that social misery is the primary cause of Islam’s expansion in the suburbs.

This observation, however, leaves 25-year-old Anissa perplexed. The law and foreign languages student grew up in an impoverished neighbourhood of Val d'Oise, near Paris.

In a span of four years, she has built a strong religious devotion through various readings and comparing sources of knowledge. In 2011, she decided to start wearing the hijab. While she agrees with the observation of the pauperisation of suburbs, she challenges Kepel’s method.

“All the neighbourhoods are not undergoing the same realities. It is true that there are unemployment and social inequality problems, but in my opinion, the current religious revival is not the result of social frustration,” she exasperatedly told Middle East Eye (MEE). “Around me I see highly educated people who feel good about themselves and are not seeking to find in Islam a therapy to their malaise.”

For Jaouad, a suburb resident and community activist in Seine-Saint-Denis, the concept of “suburban Islam is related to fantasies and illusions promoted by the media”. Skeptical about the findings, he criticises Kepelfor “not going deeper in his research”. He told MEE: “People using faith to find solutions to their problems do not remain for long on the religious path.”

Beyond the social reality, the core issue is the “lack of knowledge”, he said. “There are initiated/knowledgeable persons who read and compare scholars’ opinions, and on the other hand there are the uninitiated who are fooled by a preacher’s speech. How could you understand the message of Islam if you do not master the basics?”

An intellectual approach that is not followed by all

This observation is shared by Samy Ullah, a web designer who converted to Islam. His father, a Muslim originally from Bangladesh, and his mother, who was born to a Christian family and adopted by a French Catholic family, did not really provide him with a religious culture.

“I rather grew up in atheism,” he told MEE. Until the age of 13, Ullah lived in an impoverished neighbourhood. “When my parents divorced, I moved to live with my mother in a different town in the Essonne area.” As he had kept close relations with his childhood friends, he returned to his hometown and settled alone. “Gradually, through my acquaintances, I became interested in Islam. I was trying to find myself, with my parents' divorce it was not easy,” he said.

Then, to his mother’s great displeasure, he converted. “At the beginning, it is true, I was only in a process of mimicry. I focused on appearances to show off my conversion.”

Two years after Ullah’s conversion, he adopted “a more intellectual approach.” The entry point was Malcolm X. “I read his biography and spiritual journey.” Ullah then increased his readings and became receptive to knowledge.

As for the religious currents in the neighbourhoods, Ullah explained having “mixed with the Tabligh movement, but not identified with its approach.”

“Today, I do not feel affiliated with any movement. I just prefer checking sources [of knowledge].” It is worth pointing out that in his neighbourhood, from early on, Ullah was warned against extremist currents, even if he reports “having never been approached by the ultra-extremist Takfir movement, for example”.

The dangers of the internet

The risk of deviations is to be found elsewhere, according to Samy Ullah: “on the internet”.

In his opinion: “Clearly, the web is the operator of radicalisation. Many converts, in particular, will seek knowledge on the internet, thereby becoming prey to any extremist activist.”

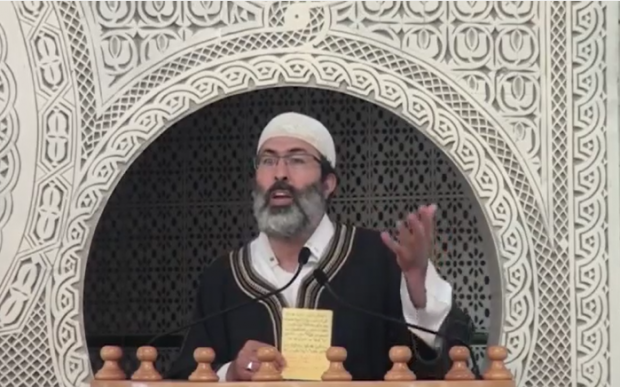

This view is shared by Nourredine Aoussat, imam of the mosque of Athis-Mons, in the Essonne department, who is more concerned about the internet than about the presence of religious currents in the suburbs.

“We discourage young people from learning on their own or by solely relying on the internet,” he said to MEE.

Aware of not being able to prevent young people from acquiring their knowledge via the internet, Aoussat, through his sermons or consultations, makes sure he cautions the faithful. “Many of them ask us for advice after reading things on the internet. We have been alerting them [to the dangers] for many years now.”

Aoussat assumes both a social and civic role. He doesn’t hesitate, for instance, to react when an atrocity is committed in the name of Islam, in both his sermons and on the internet: “I started using video clips in order to counter the extremists’ influence on our youth,” said the 54-year-old cleric.

This year, he produced four videos, including one in which he addresses al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo magazine attacks on 7 January in Paris. “I wanted to denounce their horrors and confront them with their idiocy.”

On that same line, Jaouad experienced a meaningful anecdote: “I had a discussion with a young man from my neighborhood on Muslims participating in the republican march following the attacks. On Facebook, this young man argued that we should not participate, saying he had read that on a website.” Jaouad, too, stresses the importance of countering the negative effects of the internet.

However, Aoussat observes a rise of “intellectual fervour among Muslims” in recent years. “The training courses of Islamic sciences are proving very successful,” he said.

A civic Islam rather than a suburbs Islam, so to speak, seems to be emerging.

According to Jamel el-Hamri, a PhD student in Islamic thought and member of the executive board of the French Academy of Islamic Thought (AFPI), told MEE: “’Islam of the suburbs’ links up social and territorial discrimination on the one hand, and religious and cultural discrimination on the other. The concept is derogatory, therefore problematic.”

For him, “The 1983 march for equality [the first national anti-racist movement in France] was a turning point, for it gave birth to a new category of citizen activists, ready to be at ease with their religious practice.”

Translation from French (original: http://www.middleeasteye.net/fr/reportages/islam-des-cit-s-vs-islam-citoyen-194029940)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].