What Hamas wants from Israel - and why the ceasefire talks are faltering

On paper, both sides in the US-led Gaza ceasefire talks in Cairo are working towards the same goals: a cessation of hostilities and the exchange of Israeli captives for Palestinian prisoners.

Yet, as Hamas sees it, the Palestinian movement and the Israelis are worlds apart.

The Israeli government, under domestic pressure, prioritises the release of people taken captive on 7 October.

Hamas, meanwhile, seeks not only a complete end to the war, but a future where Gaza is liberated from the blockade Israel has imposed on the coastal enclave for the past 16 years.

“The problem is, I think, that we have a strategy, and the strategy that we negotiate through is the strategy of a ceasefire, and not the strategy of a hostage exchange,” says Hamas official Basem Naim.

Middle East Eye has obtained the latest proposal passed by Hamas to Israel via Egyptian and Qatari mediators.

Like those presented to Hamas since a summit in Paris in January, it suggests winding down the war in three phases.

But whereas proposals given to Hamas have three truce periods that would, in theory, progress towards an end to the conflict, the Palestinian movement is seeking something more concrete.

'The Americans are not guarantors nor are they mediators. They are an oppositional player, they are an enemy'

- Basem Naim, Hamas official

In Hamas’s framework, phase one would see a “temporary cessation of hostilities” and the return of Palestinians to residential areas of northern Gaza.

The second phase would start with a permanent ceasefire taking effect and Israeli troops withdrawing from the Gaza Strip completely.

In phase three, Israel totally lifts the blockade it has imposed on Gaza since 2007 and a five-year reconstruction plan begins.

The document also suggests a framework for exchanging prisoners and says the guarantors of the agreement should include Turkey and Russia.

This, Naim says, is because the negotiations are tilted too much in Israel’s favour when led by the United States, which has heavily backed Israel during the war.

“At the end of the day, the Americans are not guarantors nor are they mediators. They are an oppositional player, they are an enemy,” he tells MEE.

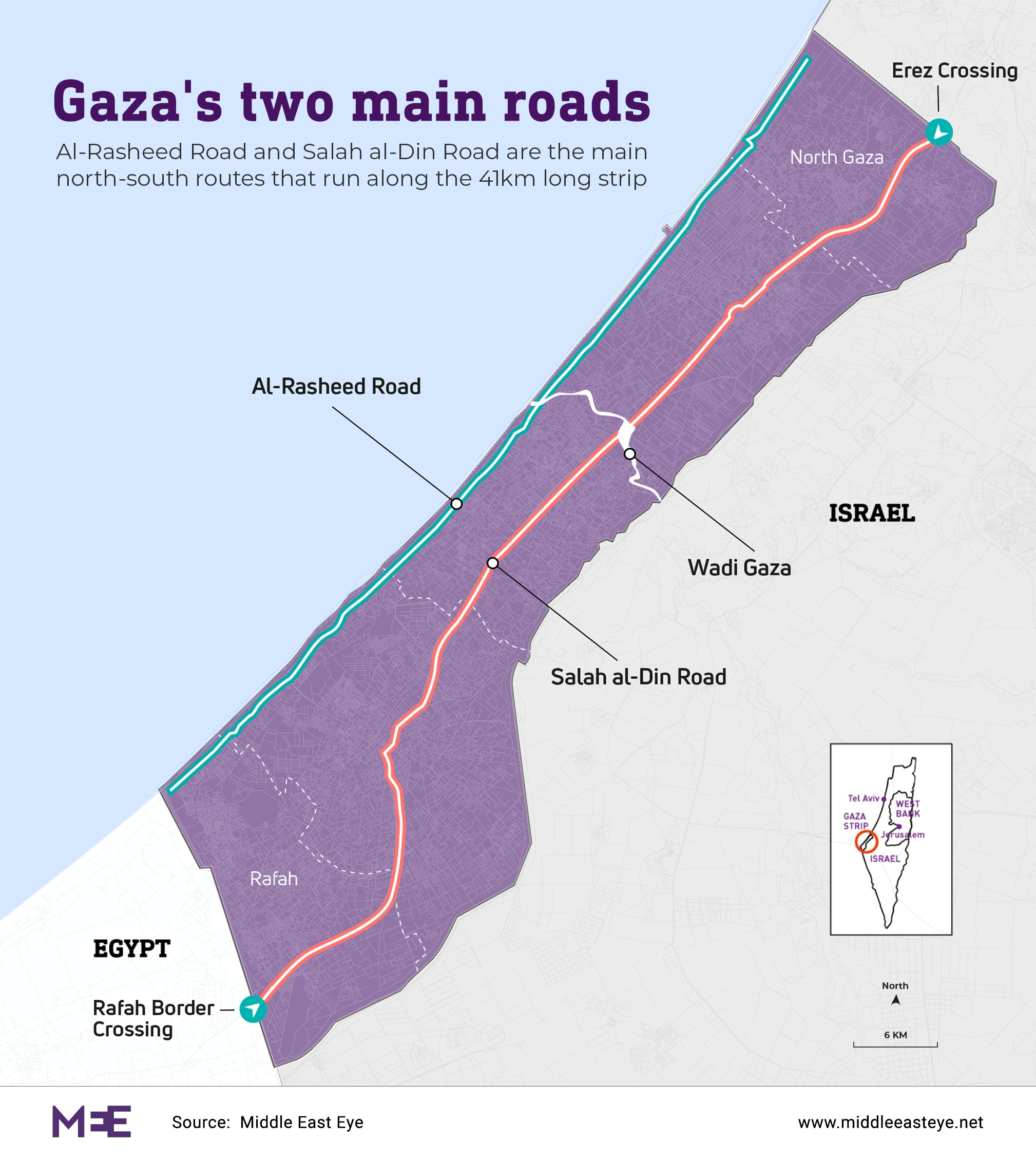

Hamas says the Israelis should withdraw from densely populated areas in stages. First, the Israelis would head east of the al-Rasheed Road that runs down the coast, “allowing free movement of the local population”.

After 14 days, Israeli soldiers should then move east of the parallel Salah al-Din Road and deploy along Gaza’s boundary with Israel, so displaced Palestinians can reach other areas of the north.

In recent weeks, the Cairo talks have focused heavily on the return of displaced Palestinians to the north.

Israel’s latest proposal suggested allowing some of the 1.7 million displaced people, most of whom are in camps around southern Gaza’s Rafah, to resettle northwards.

That flexibility has been talked up by Washington, with US State Department spokesperson Matthew Millar saying on Monday: “There was a deal on the table that would achieve much of what Hamas claims it wants to achieve, and they have not taken that deal.”

Naim, though, says the deal fell short of what Hamas deems acceptable. It was a “conditional return”, he says, with those conditions set by Israel.

“On top of that, the people would not return to their homes, but they would move into designated areas that would be predetermined on maps by the occupation,” Naim says.

Oversight and exchange

Israeli oversight over activities in Gaza is a sticking point.

Hamas says it wants United Nations agencies and international organisations to be able to carry out humanitarian aid operations immediately and unimpeded. That includes Unrwa, the UN agency for Palestinian refugees, which has been vilified by Israel and has lost at least 178 of its staff in Gaza to Israeli attacks.

The framework document also demands 60,000 prefabricated units and 200,000 tents to shelter the displaced, followed by reconstruction work overseen by the UN, Egypt and Qatar, and increased trade mobility.

Israel, according to Naim, insists on maintaining its strict controls on what enters Gaza, and this is a problem for Hamas.

“Even the aid, or anything that will come in for construction, would come in according to the conditions and restrictions of the occupation,” Naim says.

Israel says its strict regulations for goods entering Gaza are designed to avoid any potentially hazardous materials falling into Hamas hands, though aid agencies say arbitrary rules have badly impeded humanitarian relief. The UN human rights office has called the Israeli restrictions "unlawful".

Then there is the prisoner exchange issue.

Of the 240 captives taken on 7 October, 133 people - Israeli soldiers and civilians, as well as 11 foreigners - remain captive in Gaza. Perhaps 50 of the missing Israelis are believed to be dead.

Palestinian rights group Addameer says Israel holds 9,500 Palestinian political prisoners.

Hamas proposes exchanges in the first two phases, and it has different demands depending on the type of captive.

'Israel absolutely won’t talk about a comprehensive, complete and permanent ceasefire'

– Sari Orabi, a Palestinian writer and researcher

Women, children under 19, the infirm, the elderly and female soldiers would be traded in phase one. Hamas suggests each Israeli would be traded for 30-50 Palestinian prisoners, depending on their value.

Male soldiers would be released in phase two for a number of Palestinians, the number to be specified at a later stage. The remains of the dead would be handed over in the third phase, in exchange for the corpses of Palestinians held by Israel.

Wary of Israel rearresting Palestinians, Hamas wants legal guarantees for the freed prisoners. Similarly, it wants everyone who Israel freed then rearrested following the 2011 Gilad Shalit exchange to be released. It also demands better conditions for Palestinian prisoners.

Though Israelis familiar with the talks have suggested to MEE that prisoner exchanges are the least problematic side of negotiations, a difficulty has arisen. Israel demands the immediate release of 40 captives, including all the women, sick and elderly, in return for hundreds of Palestinian prisoners. Yet Hamas says not enough people meeting that criteria are still alive, and refuses to release male soldiers in their place.

No serious pressure

Sari Orabi, a Palestinian writer and researcher based in the occupied West Bank, expects Hamas and Israel to have serious difficulties as long as the Israelis are bent on continuing the war.

“Israel absolutely won’t talk about a comprehensive, complete and permanent ceasefire, the withdrawal of its forces from Gaza, alongside the lifting of the blockade and beginning the reconstruction,” he tells MEE.

“That is the main reason for the lack of ability to complete a deal.”

Hamas is in no rush to lose its leverage, particularly by releasing male soldiers.

And though popular pressure is building on Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to free the captives, public opinion is firmly against ending the war.

A recent poll found Israelis overwhelmingly believe their government should not accept Hamas demands such as withdrawing from Gaza.

Orabi says there has been no “serious pressure” placed on Israel by the lead mediator in Cairo - namely the United States - and this has also played its part.

With Washington so clearly pro-Israeli, and Egypt and Qatar merely acting as interlocutors, there is an imbalance in the negotiations, Orabi adds.

“America is a partner in this war, therefore it manages the negotiations from an Israeli perspective and for Israeli interests.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].