Why western support for Israel is not exceptional

It is often suggested that Israel is an exception to the policies of the US and western countries in their economic, military and diplomatic support for the Jewish settler colony.

Indeed, amid Israel's ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people, which has killed more than 34,000 with thousands more under the rubble, US President Joe Biden declared that there is "no red line" for Israel as his administration continued to shield it from international sanctions. And just last week, the US Congress passed a foreign aid bill that will provide Israel with an additional $26bn.

But is Israel really an exception? Looking at the history of western support for some of the well-known European settler colonies shows us unequivocally that western support for Israel is neither unique nor unprecedented, even if it varies in certain details.

It is historically true that many people who supported anti-colonialism in Algeria refused to support the Palestinian people. Similarly, many of those who supported the liberation of South Africa from apartheid insisted on supporting Israel and denouncing the Palestinians.

Still, the vast majority of those who supported French Algeria, Rhodesia, and apartheid South Africa in the West, to take three notable examples from the colonial world, also endorsed a Jewish supremacist Israel.

Shielding white supremacy

At the height of French colonial repression during the Algerian struggle for independence, the US and Europe supported France - shielding it from sanctions at the United Nations - and denounced the Algerian revolutionaries.

President Nixon, in violation of UN resolutions, decided to import Rhodesian minerals for military use in open defiance of the UN

They would maintain similar support for white supremacy in the apartheid state of South Africa, which they also shielded from sanctions at international fora from the 1960s through the late 1980s - and extended to South Africa's illegal white supremacist occupation of Namibia until 1990.

This was also the case in Rhodesia, where the British shielded their white supremacist settler colony from international condemnation before and after white colonists, led by Ian Smith, issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965 to safeguard white supremacy.

Beginning in 1962, the UN Security Council, General Assembly, and the Special Committee on Colonialism took an active role in urging Britain to end white supremacy in Rhodesia, which included a 1962 General Assembly resolution.

Follow Middle East Eye's live coverage for all the latest on the Israel-Palestine war

The British, however, refused to heed such calls. In September 1963, Britain vetoed a Security Council resolution calling on the British to oppose the transfer of the Royal Rhodesian Air Force to the Rhodesian local government.

In April 1965, before UDI, the Security Council adopted another resolution calling on Britain to prevent UDI. In October, the General Assembly passed a resolution calling on the British to use "all possible measures" to prevent UDI. Six days before UDI, another General Assembly resolution was passed urging Britain to use "all necessary means, including the use of military force" to stop the settlers from declaring independence.

After the issuance of UDI, Britain, under international pressure, expelled Rhodesia from the Sterling area and removed it from several Commonwealth preferential economic agreements. It also banned imports and froze £9 million ($25.2m) of Rhodesia's reserves in UK banks.

The UN General Assembly and Security Council passed resolutions immediately following UDI, condemning it and calling on states not to recognise it and to "refrain from any action which would assist and encourage the illegal regime…and to desist from providing it with arms, equipment, and military supplies, and…to break all economic relations."

The Security Council resolution also called for an oil embargo. Meanwhile, nine African countries broke diplomatic relations with Britain for having allowed UDI.

Britain tried to negotiate with the UDI regime again in December 1966 and in October 1968 on offshore ships but to no avail. It was only in 1968 that the British government finally asked the UN to impose international sanctions on the recalcitrant colonists, who had since 1965 shifted their financial assets from British banks to South Africa to safeguard them.

Open defiance

When the Security Council finally passed a resolution in March 1970 condemning Britain for refusing to use force to overthrow the illegal Rhodesian regime, the US and Britain vetoed it. Britain would veto another such resolution in February 1972.

In the meantime, some of the British Conservative members of parliament were apoplectic over the 1966 UN sanctions. They argued that Rhodesia was not an anomaly but an all too normal state. Indeed, "all reasonable men", one MP argued, found the UN biased against Rhodesia, as the UN did not sanction Hungary, Tibet, Zanzibar, or other "tyrannical regimes of various kinds".

In the US, former secretary of state Dean Acheson joined in and condemned the UN sanctions.

The help the UDI regime received from South Africa and Portugal (the colonial power occupying Angola and Mozambique at the time) was instrumental in the survival of the white supremacist settler colony. That West Germany, France, the US, and Japan did not observe the UN-mandated boycott scrupulously, by looking the other way, contributed to that survival.

When the new conservative British government of Edward Heath came to power in 1970, it resumed negotiations with the UDI regime. On 24 November 1971, it reached an agreement with it ("The Anglo-Rhodesian Settlement Proposals"), in which Britain accepted Rhodesia's independence and guaranteed white supremacist rule until 2035 at the earliest.

The US, meanwhile, which had initially loosely observed the boycott, changed its mind in 1972 on account of the British agreement. President Richard Nixon, in violation of UN resolutions, decided to import Rhodesian minerals for military use, joining South Africa and Portugal in open defiance of the UN.

Unrelenting support

In the case of South Africa, in 1963, the US, Britain, and West Germany, among other European countries, refused to abide by a UN Security Council non-mandatory ban on the sale of arms to South Africa.

In 1973, the UN General Assembly also declared apartheid to be "a crime against humanity". Yet western countries did not relent in supporting the apartheid regime, investing in it economically, and providing it with weapons.

The fall of Angola and Mozambique at the hands of African revolutionaries and the end of Portuguese colonial white supremacy in 1975 brought about the first major international disaster for the apartheid regime.

In 1973, the UN General Assembly declared apartheid to be 'a crime against humanity', yet western countries did not relent in supporting the apartheid regime

By the time Rhodesia was replaced by Zimbabwe in 1980, and the revolutionary war for liberation in Namibia had accelerated, South Africa found itself alone in hoisting the flag of white supremacy across Africa. By then, its only remaining major allies, aside from the US and Western Europe, were the fellow settler colony of Israel and Kuomintang-ruled Taiwan.

When the UN finally imposed a mandatory international arms embargo on the country in November 1977, two months after discovering that South African police killed Steve Biko, Israel and Taiwan refused to abide by it and continued to send weapons. This was the first time the UN had imposed such an embargo on a member state.

Economically speaking, by 1978, the Americans were South Africa's largest trading partner, followed by the British, the Japanese, West Germany, and other European countries.

As for foreign investment in the country which surpassed $26bn that year, 40 percent was British capital, 20 percent was American, and 10 percent was West German - investments that had a high rate of return in the 1960s and 1970s.

Indeed, the lack of US interest in the suffering of the Black population of South Africa was such that John Hurd, the US ambassador and Texas oilman, went pheasant hunting on Robben Island (where Nelson Mandela and other ANC and African leaders were incarcerated as political prisoners) with then-Minister of Transport Ben Schoeman in 1972 and used political prisoners as beaters. The State Department rebuked him for his "lapse".

Western shamelessness

Internationally, in the mid-1980s, the refusal of the South African regime to make major concessions led to an increase in international condemnation. The US (under pressure from a domestic mass movement opposing apartheid and demanding divestment) and most Commonwealth and European Community countries increased divestment and economic sanctions.

The only remaining holdout was Margaret Thatcher, who continued to support the apartheid regime with trade and economic links. But when a Commonwealth delegation visited South Africa to assess the situation in May 1986, the South Africans refused to downplay their aggression.

With the delegation in the country, South Africa raided alleged ANC bases in Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Botswana. More condemnation ensued, this time including Thatcher. According to a British Commonwealth committee, between 1980 and 1989, South Africa's invasions and sponsorship of counter-revolutionary groups that started civil wars in neighbouring countries led to the death of one million people, made three million homeless, and caused $35bn worth of damage to the economies of neighbouring states.

The apartheid regime began to make concessions by easing apartheid laws and eventually repealing them amid the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist camp. This removed the communist threat that South Africa and the western imperialist countries used as a pretext for their long-term support of the apartheid regime.

It was then that the imperialist powers exercised sufficient pressure on the South African government to end the ban on the ANC and release political prisoners. Indeed, as the neoliberal age was about to overtake the world, the moment was seen as most apt to integrate the ANC into the new arrangement.

Mandela immediately suspended the armed struggle and began negotiations. This led to the easing of international economic sanctions and sports boycotts.

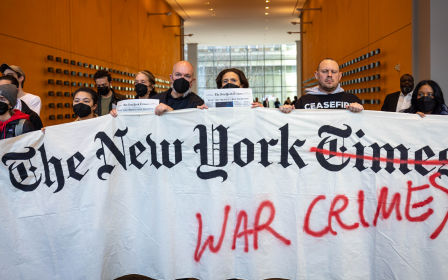

Revisiting some of this history is essential for those who support the Palestinians today and who marvel at the shamelessness of those in the West who continue to support Israel as it continues its genocide against the Palestinians.

These supporters of Israel were just as shameless when they actively supported white supremacist rule in French Algeria, Rhodesia, and South Africa. Israel is hardly an exception in this shameful history.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].