Why is Israel so vulnerable?

Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud Party has prevailed after a bitterly fought election in Israel. He will now be horse-trading with smaller right-wing and extremist parties to form a coalition under the country’s complex political system. Although this will be his fourth premiership, the Netanyahu effect has proved extremely divisive in Israeli society. In any event, the talk of Israel’s political left and right is utterly meaningless when it comes to Palestinian citizens of Israel, Palestinians living in the occupied territories and Israel’s image in the wider world. The past is the future in this context, and the most fundamental problem for Israel is that of legitimacy of its conduct.

States and governments emerging out of conflict often have to struggle for legitimacy at home and abroad. Legitimacy is about establishing virtues of their origins, qualities and behaviours of political institutions, their decisions and consequences thereof. Legitimacy requires acceptance of those virtues nationally and internationally. We hear justifications for the conduct of Israel continuously. So how the Israeli state and governments fare in terms of their legitimacy is a question which must be examined continuously.

How policies and laws affect citizens is part and parcel of the pursuit of legitimacy. The coercive ability to impose authority by direct or indirect methods is important to establish legitimacy, but it is insufficient and cannot substitute for the rule of law. Equality of all citizens before the law, including rulers, is essential - a concept which stands against autocracy or dictatorship, narrow oligarchy or wealthy plutocracy.

What is the status of Israel’s non-Jewish minorities? How are Israeli-Arab citizens, mostly of Palestinian origin, treated within Israel? And how does Israel treat Jews and non-Jews living in the occupied territories? Indeed, how should Israel’s occupation of Arab territories since the 1967 war be interpreted? Can Netanyahu’s claim of Israel being a “Jewish democracy” be valid? After all, the very essence of democracy is that all citizens are equal, and that minorities must have appropriate protections to ensure equality.

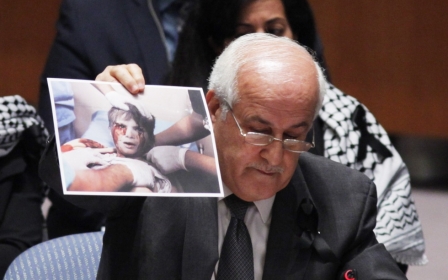

Such questions point to Israel being not a strong, but a weak state armed to the teeth with weapons, and immunity ensured only by the American veto in the UN Security Council.

The 1967 Six Day War established Israel as the dominant military power in the Middle East. The armed forces of Egypt, Jordan and Syria were heavily defeated. Israel captured the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip from Egypt, the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria. A quarter of a million Palestinians and a million Syrians were made refugees. That is how the conflict became perpetual.

In victory, Israel acquired the label of occupier, but the law of war required Israel, like any combatant, to limit the suffering to affected people, in particular to non-combatant civilians. It means protection for the injured, the sick and prisoners of war, together with vulnerable civilians. With a history of forced evictions of Palestinians from their homes, questions raised over Israel’s conduct in the 1967 conflict, and the resulting humanitarian crisis, would not go away.

Israel fought another serious war with Egypt and Syria in 1973, but its outcome meant that the main thrust against Israel thereon came from Palestinians under Yasser Arafat’s leadership. The will of Arab states to go to war against Israel faded after the 1967 defeat.

By September 1978, Egypt’s Anwar Sadat and Israel’s Menachem Begin had signed the Camp David accords, followed by the Israel-Egypt treaty. Resistance from Arab governments had weakened and Arab governments, except Syria, learned to pay only lip service in support of the Palestinians.

The legitimacy of Israel’s conduct is challenged today more than before for three main reasons. First, the logic of Israel’s fragility in military terms is no longer valid. Its frailties are of a different kind. Questions about Israel’s legitimacy have much more to do with how it uses its overwhelming military power against non-Jewish people - Palestinians who live under Israeli control.

Second, not only does the question of occupation of Arab territory since 1967 remain unresolved, but hundreds of thousands of Jewish residents have been settled in the occupied territories. Most Jewish settlers have been encouraged to move from Europe, the United States and the ex-Soviet Union. The Palestinian economy in the occupied territories is in the control of, or heavily dependent on, Israel. Palestinian workers sustain the lifestyle of wealthy Jewish residents living in illegal settlements in the West Bank, and Gaza is besieged.

In the midst of the recent election campaign, Prime Minister Netanyahu announced that Israel will not cede territory to Palestinians, ruling out the establishment of a Palestinian state. Netanyahu asserted: “Any evacuated territory will fall into the hands of Islamic extremists and terror organisations supported by Iran. Therefore, there will be no concessions and no withdrawals. It is simply irrelevant.”

Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman went beyond the prime minister. Addressing a rally in Herzliya, Lieberman issued a call for the beheading of Arabs not loyal to the state of Israel. Netanyahu himself is engaged in a push to alter the country’s basic law that would assert that “Israel is a nation-state of one people only - the Jewish people - and no other people.” In truth, Israel’s declaration of independence in 1948 already defines the country as a Jewish state.

These developments have put almost two million Palestinian citizens of Israel under great pressure. Surely, a state that treats minorities differently under the constitution cannot call itself democratic, because the essence of democracy is equality of treatment under the law. The question of democracy is inevitably tied to the legitimacy of the Israeli state’s behaviour, which gets worse when consideration is broadened to include Israeli conduct in the occupied territories.

The population of Israel proper comprises just over six million Jews and nearly two million non-Jews. Non-Jews are mostly Arab or Palestinian who describe themselves as Palestinian citizens of Israel, but there are other groups, too. Consider four-and-a-half million Palestinians, and nearly seven hundred thousand Jewish residents of illegal settlements, in the occupied territories.

Therein lies Israel’s nightmare which evokes parallels with the bygone apartheid era in South Africa before white supremacist rule collapsed in the early 1990s. The most fundamental question challenging Israel’s legitimacy is: How can a state be democratic and claim to be legitimate if it treats half its population differently, and constantly invents ways to maintain Jewish supremacy which are both discriminatory and enduring? Attempts to invite Jews from all over the world to settle in the “land God gave to Jews” can be explained by this nightmare.

he views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A man carries a container of water on his head as he walks on scorched earth (AFP)

- See more at: http://www.middleeasteye.net/columns/new-age-water-wars-portends-bleak-future-804130903#sthash.GyHpO4JL.dpuf- Deepak Tripathi is a writer with particular reference to South Asia, the Middle East, the Cold War and America in the world. He is a fellow of the Royal Historical Society and the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Questions about democracy in Israel suggest it is a weak state armed to the teeth with weapons, and immunity ensured only by the American veto in the UN Security Council (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].