Deaf in Palestine: Society outstrips government policy

RAMALLAH, West Bank - “Ten years ago, most Palestinians gawked if they saw sign-language on the streets,” remembers Suheir al-Badarneh. “They’d look at you strangely. But attitudes are changing now. It’s better than before.”

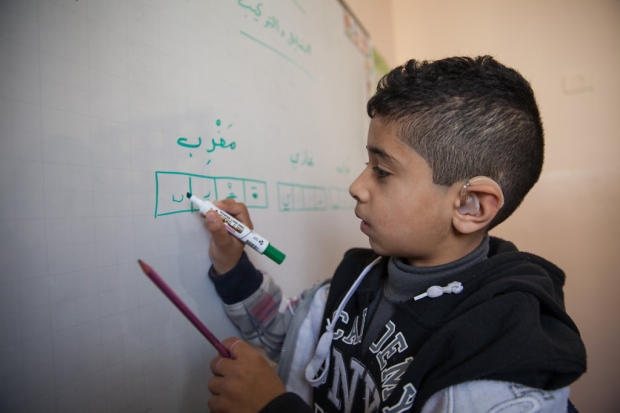

As director of the rehabilitation department at the Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS), Suheir heads a deaf school, one of only 11 in the West Bank. Compared to a decade ago, she says educational opportunities for the deaf are markedly improved, and the social stigma that shamed many families into hiding their deaf children at home is waning.

“Families have started to treat their deaf children differently because there are opportunities now,” she told Middle East Eye. “Deaf children in Palestine can go to school, they can work.” Before, PRCS went to lengths to reach out to reluctant families with deaf children. Now, families are contacting its early intervention unit to diagnose children as young as one month old.

But Suheir and her colleagues at the 10 other deaf schools in the West Bank feel they are fighting a lonely battle. Frustrated by the government’s lack of involvement, they maintain that the Ministry of Education in Ramallah is failing to implement policies that create opportunities for Palestine’s deaf youth.

Suheir believes the “change in society’s attitudes is more evident than change in the government’s education policy”. With some hesitation, she adds that the Ministry of Education’s role in deaf education is roundly “limited to the support they offer NGOs and charitable schools”.

All 11 deaf schools in the West Bank are operated and funded by NGOs or charities. Combined they enrol 700 deaf or hard-of-hearing (HoH) students. Beyond subsiding teacher salaries and donating books, the ministry offers scant support to these schools.

Of 27 teachers at PRCS deaf schools, the Ministry of Education pays salaries for 10. At the Islamic Charitable Society deaf school in Ramallah, the ministry pays for less than one-third of the staff, but donates some materials, including books.

Horia Safi, who has been headmistress of the Islamic Charitable Society deaf school since the mid 80s, says her school is in particular need of government support, since international donors have proven less inclined to support a charitable society with religious connections. Would-be donors, she says, “are put off by our name”.

Safi's Islamic school is further burdened, because, unlike other deaf schools, hers provides housing and food to deaf students. Neither classes nor room and board at the charitable school come at any cost to families.

More than 800 deaf/HoH children in the West Bank who aren’t afforded the benefit of attending NGO- and charity-run deaf schools are “integrated” into the public school system. But by the Ministry’s own admission, enrolling deaf/HoH students into public schools is mired by obstacles, not limited to a lack of properly trained staff and stilted communication between deaf students and hearing teachers.

The head of Special Education Institutions at the Ministry of Education, Khalil Alawni, says that the roughly 800 HoH and 100 deaf children integrated in public school system would be better catered for in any of the privately operated deaf schools.

NGO and charitable schools agree. “We want to be very realistic,” says Suheir at PRCS. “We can’t say that public schools are prepared to integrate children with hearing loss.”

There is little evidence to suggest Palestine’s Ministry of Education in Ramallah will assume a more prominent role in deaf education in the immediate future. Alawni says that beyond early-stage talks with Scandinavian donors to open a deaf high school in Ramallah, the Ministry is focused only on identifying systemic issues and potential solutions with its integration policy.

Even assessing NGO and charitable schools’ reach in Palestine is problematic. The Palestine Bureau of Statistics’ most recent figures on deaf/HoH Palestinians is four years outdated. “We can estimate how many children are still in homes,” says Suheir, “or how many are integrated into public schools, but we can’t even be sure of the numbers.”

The bureau’s dated figures suggest that approximately 17,000 Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza are deaf/HoH. Compared side-by-side with current deaf school enrolment, PRCS estimates that at best, only one-third of the deaf/HoH school-age population is either in NGO or charitable schools, or integrated into public schools.

There are signs of hope for deaf/HoH students in Palestine beyond the work spearheaded by West Bank NGOs and charities. Surprisingly, these glimmers come from Gaza.

Educational resources there easily surpass opportunities in the West Bank. Six schools in Gaza enrol 1,700 deaf/HoH students, which amounts to nearly half as many schools enrolling twice as many students as in the West Bank.

Gaza’s encouraging enrolment figures are mainly the result of a new school, the Mustafa Sadeq Rafaee Secondary School for the Deaf, founded and funded by the Hamas government in Gaza City. It’s the only fully government-funded deaf school in Palestine.

More than 160 students are enrolled at the gender-segregated deaf school, which opened in February 2011. Over 120 - nearly five times more than in the West Bank - graduated last year, passing the government’s matriculation exams, known as Tawjihi, with some graduates going on to earn places in Gazan universities. Seventy will sit the Tawjihi this summer.

Not only does the Mustafa Sadeq school in Gaza educate deaf/HoH Palestinians without cost to families, but it provides transportation to and from the school for its student population. This, says Hassan Nassar, a deaf teacher at the Palestinian Red Crescent in Gaza, is a major obstacle to student engagement in the West Bank, where the cost of transport to deaf schools has proven to be prohibitively expensive for families with limited incomes.

While opportunities for primary and secondary education are scarce, but improving, those for deaf high school graduates seeking work or university education are nearly nonexistent. Even though universities in the West Bank have begun accepting small numbers of deaf high school graduates, these students would struggle without the continued support of NGOs and charities.

“Even though we know it’s not our role, says Suheir, “we provided our PRCS graduates in universities with volunteer interpreters who could support them in university classes. We know if we didn’t provide this assistance, the students wouldn’t continue.”

Already stretched for resources, and with seven of their graduates in universities, PRCS understands that without their continued support, universities are unlikely to subsidise resources deaf/HoH students require, particularly interpreters.

Hassan Nassar sees increased university enrolment among deaf students as “a positive step” but criticises universities that restrict course offerings for deaf/HoH students, particularly at the Islamic University in Gaza: “If the students passed the Tawjihi exam, they should be allowed to study in any department they are qualified for, not only those designated for deaf students.”

Employment prospects are also improving, but slowly. The British Council in Palestine and PRCS are offering vocational training workshops - metalworking for boys, hairdressing for girls - to improve employment opportunities for deaf/HoH high school graduates. The British Council has led ceramics workshops for deaf/HoH Tawjihi graduates, some of whom are now teaching hearing students. These initiatives, though promising, are still in the early stages of development.

David Tawil, 21, was born with profound hearing loss towards the end of the First Intifada near Bethlehem. David left Palestine with his family for the US when he was 12 years old, around the same time Suheir says opportunities for Palestine’s deaf began to show promise.

Despite the recent growth in opportunities for Palestine’s deaf community, David, who is now studying business accounting at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf in New York, says he is not tempted to return to Palestine. “I want my life to be in the US. Compared to Palestine, life here is better, there are more opportunities.”

Additional reporting by Richard Freund

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].