In Morocco, it’s the women who carry the Atlas

TIZI OUSSEM, Morocco – Every day after lunch, the women of the village of Tizi Oussem walk down a steep rocky path to the valley. They work the fields, herd the cattle, do the laundry by the river and gather wood for the fire. Even before that all starts they will inevitably have already worked for half a day doing household chores and taking care of the children.

At the end of the day they gather the wood or crops into bundles which they hoist onto their shoulders and carry back up to the village. Then they start preparing dinner and beginning their chores for the evening.

In this Amazigh region, the women take care of pretty much everything. That includes the carrying of very heavy loads. Whenever you see a bundle of wood or hay being transported by a human here, it’s women’s legs carrying it.

“It is a tough life, but it is what it is”, says Yemna Ait Lmalame, one of the women of the village. Like all the older women, she can’t read or write, and she doesn’t really know how old she is. “This is the life of the mountains. It’s good, but we also don’t really have a choice. Why don’t men carry the heavy burden? I'm not sure, but most of them just don’t.”

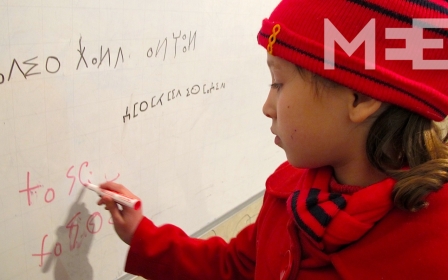

Ait Lmalame points at her granddaughter Samira, a bright 12-year-old with sparkling eyes. “I hope she will lead a different life. But in order for that to happen, we'd have to send her to a school far away, and that costs money.”

Last stop

Tizi Oussem lies at 1800 metres in the heart of the High Atlas mountain range, close to the Toubkal, Morocco’s highest peak. Asphalt doesn’t exist here; the village is the last stop on a rocky dirt road through the beautiful and - in summer- lush Azzaden valley, a nearly two-hour drive from Asni, past deep ravines. It has a primary school, but the secondary school is in the next village. To get to a high school, the children have to travel outside the valley.

The families of Tizi Oussem live off their cattle and what they make of the crops of their lands, mostly apples, walnuts and cherries. Whatever they gather in summer is needed to get them through winter. Recently, the 140 houses - home to some 750 or so people - of Tizi Oussem got snowed in for twenty days and food and resources had to be rationed.

“That too, is part of mountain life,” says Lahcen Bounasser, 52. He is one of the key figures in the village and has multiple responsibilities; he has to call an emergency if someone is in danger, when a woman has to give birth or when the roads are blocked in winter. He settles disputes and when a family suffers from poverty, he makes sure other villagers help out. In this Amazigh region, people take care of their neighbours. “We like our way of living. When we have a good harvest, life is good. When the harvest is bad, life is rough.”

He agrees life can be difficult in the valley, especially for women. They do 100 percent of the work, far more than the men, he says. “Yes, they carry heavy loads here. It was like that in the days of my father and my grandfather, it’s our tradition. Some people here think it’s bad for a man's reputation, if a he does a woman’s work.”

The men leave

However, that is not the only reason women carry the weight of the Atlas, he emphasises. At least two dozen men have recently left Tizi Oussem, leaving their wives and children behind, because there just isn’t enough work. They went to find jobs in cities like Marrakech, Agadir and Casablanca. “Usually they barely make enough to get by,” says Bounasser. “They work for six, seven Euros a day, but the cost of living in the cities is higher. The families here don’t really profit from them, and neither does the village. It would be better if they stayed here to make this a better place.”

There are hundreds of villages like this in the Atlas, says activist Fouad El Agguir. He sits in a local coffeehouse in Demnate, about a 150 kilometres northeast of Tizi Oussem, and is a member of The Moroccan Association of Human Rights (AMDH), the largest human rights organisation in Morocco. “Men often work outside the villages, women are mostly illiterate, people are poor. It’s the result of years of marginalisation”, he says. “The government invests in cities like Tangier, Casablanca and Agadir, but not really in the rural areas.”

The main problem is the lack of roads, he says. The main roads in Demnate are fine, but take a left or a right turn and the asphalt turns into sand. Recently he visited a village deep in the Atlas, he says. It was a four-hour trip, the last part of which he rode on a donkey because there were no roads. Those remote areas lack basic needs like health-care and schools, he says. “If a woman is pregnant and something goes wrong, she has to come to the hospital in Demnate. To see a gyneacologist, she has to go to Marrakech or Beni Mellal, which is at least another hour away. The government is investing in things like a high speed train, but these people don’t even have their most basic needs met. Thousands upon thousands of people live like this in the rural communities.”

Off to Marrakech

Back in Tizi Oussem, Jamou Ait Talb Mbark is tending to her cow under one of the apple trees in the valley. At the same time, she looks after her young daughter. Ait Talb Mbark is one of the women who regularly saw her husband leave the village. When he’s at home, he works the fields just like her, or helps in the construction of new houses.

But when he’s off to Marrakech to find a job, the work lies on her shoulders, literally; her four children, the livestock, the harvest, the household. “Women have to do a lot in one day”, she says. “That’s why I hope at least one of my daughters will marry someone outside the valley, for a better life, or get a good education, even though we cannot save money to pay for the expenses. We’ll try our best.”

Later in the afternoon, Yemna Ait Lmalame has taken her sheep down to the river to feed them. She sits watching the water flowing by and says: “A lot of boys and girls in the valley marry at a very early age. They see it as a solution, as a form of security. I understand, but I also think that it’s not a rational decision. They don’t think ahead. Maybe instead they should better their future while they are still young, and marry later but this way, nothing changes. Not for them, and not for their children.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].