The story of a missing Mediterranean migrant

As reports of thousands of migrants dying in the Mediterranean flooded in over the past week, the memory of many tragedies resurfaces, bringing to life the story of 24-year-old Sajed Nafez, a Gazan who attempted the risky journey last autumn.

Like many Mediterranean migrants, Sajed was in search of a future after the summer 2014 Gaza War had cost him his dream – a media production company which he had set up a year before.

The office and all the team’s equipment was destroyed when one of the final Israeli airstrikes hit a central Gaza building, just two hours before a ceasefire was announced on 26 August 2014.

Less than two weeks later, on 6 September 2014 and after 10 failed attempts, Sajed left Gaza through an underground tunnel and boarded a ship from Alexandria in Egypt that would cross the Mediterranean and land him in Europe.

“After he lost his company, I could see him getting paler and thinner every day,” said Sajed’s sister Nour, as she described a miserable Gaza in the aftermath of the war.

“I encouraged Sajed to go. He said the traffickers had family members on the ship; I thought it would be all ok,” said Nour, who shared an especially close relationship with her younger brother.

Sajed had secured a scholarship offer in Turkey where he intended to pursue a master’s degree in cinema and film studies. After the war, Gaza's border crossing were all blocked off and one of the few ways to leave the Palestinian enclave was on migrant boats.

A literature graduate of Gaza’s Islamic University, Nour had also planned to join Sajed when he settled, and pursue her graduate studies there.

But only six days later, his family received news that Sajed, along with 500 other migrants – including other Palestinians, Syrians and Egyptians – were feared to have drowned when their boat was apparently rammed and deliberately sunk by traffickers near Malta.

“We received a phone call from one of the few people who were rescued. He said that Sajed had been floating at his side for three days until they lost him, unconscious, to the water,” recounted Nour.

There was no verification of what happened to the Italy-bound vessel, mainly because only nine people are believed to have survived, the Geneva-based International Organisation for Migrants (IOM) said at the time.

According to survivors' accounts, the traffickers had rammed into the boat after passengers refused to shift onto a smaller vessel, for fear it would capsize, said Nour.

"Most women and children were moved to the basement when a fight between the traffickers and the passengers broke out onboard the ship. Apparently, they [women and children] were the first to drown," she said.

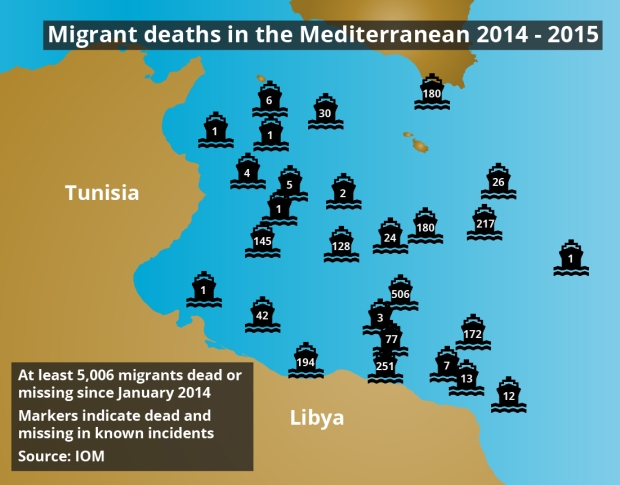

The issue of migrant deaths in the Mediterranean has escalated since the beginning of this year, with recent accounts saying more than 1,750 migrants have perished at sea since the start of the year - more than 30 times higher than during the same period of 2014, according to IOM.

When a migrant ship sinks at sea, the passengers on board may end up in a number of scenarios: some passengers survive and are rescued, others die and their bodies are recovered, while a great majority go missing.

Verifying the death of missing persons however, is among the most difficult tasks for organisations and state authorities working on an incident.

“We rely on what eyewitnesses tell us," said Joel Millman, press officer at IOM.

"In times when we have more survivors, we often know the names of those that perished because someone who knew them was at their side when they drowned,” added Millman.

But with less than a dozen survivors on the ship Sajed had boarded, chances of verifying information were quite low.

"No-one is diving into the waters trying to find the wreck. It’s what the intelligence community would call uncorroborated information,” said Millman.

Like Nour, family members are left to embark on a witch hunt of their own in search of their loved ones.

“The Italian Red Cross kept referring me back to the Gazan Red Cross, while the coastal guards would only tell me that they had thousands of cases to deal with every day,” Nour said describing her many disappointing phone calls with authorities telling her information could not be disclosed over the phone.

She therefore applied for visas to Malta, Greece and Italy – locations at which survivors of the incident had been found - but her applications were all rejected.

After months of failed attempts to leave Gaza for more direct engagement in the search for her brother, Nour jumped at an opportunity to attend a teaching course in London – a place she believed could be a jumping board to find Sajed.

She secured a visa to the UK and in early January 2015 left Gaza through the Rafah border crossing when it was opened on two brief occasions that month.

Compiling a thorough report of all the information she had gathered about the incident and mapping out possible scenarios of Sajed’s whereabouts, she contacted and met several authorities and aid organisations – including members of the British parliament, the Red Cross and Amnesty International - during her stay in London.

She says, however, that little has come out of her many meetings, emails and months of waiting.

“They all sent emails here and there and then told me to wait. I really thought they would be more helpful than this,” said Nour explaining her disappointment.

Although to Nour it seems that more efforts should be made to locate her brother, as time passes, there is less of a chance missing persons will be found at all, let alone alive.

“We usually don’t know any more information than what we gather over the few days and weeks after an incident. After months have passed, the likelihood of people reappearing is quite slim,” he added.

But, Nour – despite the challenges – believes there is always a possibility that Sajed is alive, yet unable to reach out.

“He could be in an Egyptian prison, at an immigration camp in Italy or Malta, or in some sort of trouble preventing him from contacting us,” said Nour, as her eyes filled up with pain and reminiscence at the mention of possible danger her brother could be facing as she spoke.

One survivor of the incident was indeed found in Egypt’s Azuli prison, a military jail facility - known by the name of Egypt’s secret prison - where many detainees and missing persons face extreme conditions and torture.

Although Nour hopes to find Sajed safe and alive anywhere, she wishes he is not in an Egyptian prison where many refugees are caught in extreme conditions.

According to Meron Estafanos, a journalist and human rights activist, missing migrants to the Middle East are more likely to be alive than those headed to Europe.

Although Sajed's boat sank off the shores of Europe, if by some chance he is in Egypt, Sajed may be in a prison with no access to a phone, or - as in the case of many African migrants - in a hidden migration camp facing torture or his family being extorted for ransom.

"There are those that die at sea. But it is likely in the Middle East, that people who go missing are alive - in prison or kidnapped," said Estefanos, whose work focuses on finding Eritrean and Ethiopian migrants that have disappeared.

Although most times her difficult work comes to nothing, Estefanos has in some instances reconnected families with their loved ones after years of searching.

Nour is currently trying to travel to Malta after she received fresh news that another survivor was found by the Swedish Red Cross on the Mediterranean island.

According to the news she received from the survivor’s father, there are ten other individuals with his son – Nour believes one of them could be Sajed.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].