Neoconservatives ruined David Cameron's foreign policy realism

In the days when I worked as a political reporter I used to speak often to David Cameron, then a young, up and coming politician. I liked him very much. The future prime minister was decent, courteous, sensible, honest and highly intelligent.

After five years in 10 Downing Street he remains (to his credit) remarkably unchanged. But there is one puzzling exception. Mr Cameron’s views on foreign policy, and in particular the Middle East, are completely different to those he used to hold 10 or 15 years ago.

Back then he was conservative in the old-fashioned sense of the term. He was sceptical of foreign adventures and pretty well immune to popular clamours.

He only voted with reluctance for the invasion of Iraq in 2003. During the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 2006, he permitted William Hague, his foreign affairs spokesman, to describe Israeli conduct as "disproportionate," a sentiment which led to open revolt among some pro-Israeli supporters of the Conservative Party.

Today David Cameron is a neoconservative. Along with President Sarkozy of France, he led the way in the Western intervention in Libya four years ago. Eighteen months ago he wanted to intervene militarily against President Assad, and was only deterred by a parliamentary vote.

One mark of neoconservatism is uncritical support for the state of Israel. Mr Cameron has become the most vocal international backer of Benjamin Netanyahu. Mr Cameron has gone out of his way to repeatedly defend the conduct of Israeli forces during the Israeli invasion of Gaza last year.

Mr Cameron regularly seeks advice from Tony Blair. Mr Blair was one of the circle of advisors urging David Cameron to bomb Libya. In foreign policy terms, David Cameron should indeed be seen as a protege of the former prime minister. Both men have been steadfast supporters of the Gulf dictatorships and of Netanyahu’s Israel, and both men are unbendingly hostile to democratic movements within Islam, in particular the Muslim Brotherhood.

David Cameron has protected Tony Blair. Had Mr Cameron wanted, he could have insisted on the publication of the Chilcot Inquiry into the Iraq War, which is expected to contain damning criticisms of Mr Blair.

This investigation was meant to publish its conclusions within 18 months of the British withdrawal from Iraq in 2007: it is disgraceful that eight years later, Sir John Chilcot is still at work.

Before the 2010 general election, David Cameron also promised an investigation into the very serious allegations that Britain was complicit in torture and extraordinary rendition during the Blair premiership. Instead the investigation has been suppressed.

So what happened to the foreign policy realist I used to talk to a decade and more ago? I believe that part of the explanation lies in David Cameron’s near total lack of knowledge of the world beyond Britain when he was elected prime minister. Beyond beach holidays in the Mediterranean it was negligible.

This ignorance created a vacuum which has been filled by the small, well-knit and very powerful clique of neoconservatives who surround the prime minister. The two most important of these are George Osborne, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and chief whip Michael Gove.

These are not really Conservatives in the traditional sense of the word, and essentially feel themselves far more at home in the smarter right-wing cadres of the US Republican Party. They are both backed very strongly by the Murdoch press, which remains by far the most significant force in British media notwithstanding the phone hacking scandal.

Michael Gove has drawn much of his inspiration from neoconservative think tanks. His book Celsius 7/7 is a lurid work which divides the globe between benign western liberal democracies and barbaric Islamic movements. Mr Gove was one of the most eloquent cheerleaders for Tony Blair and George Bush's catastrophic invasion of Iraq.

One of the most puzzling phenomenon of the last decade has been the continued success of neoconservative doctrines, long after they have been discredited by the twin calamities of Iraq and Afghanistan. Part of the answer lies in the capture of the 21st century Conservative Party by a neoconservative clique.

This is why I believe that today's general election has the potential to be a breakpoint in British politics. Ed Miliband has a much deeper understanding of the outside world than David Cameron did when he became prime minister five years ago.

This is not surprising, since he is the son of remarkable parents. They were Jewish, fled the Nazi holocaust, and gave him a wider international outlook, as well as a deeper understanding of the tragedy of history.

He was an opponent of the Iraq invasion, and led the parliamentary opposition to the planned military intervention in Syria in 2013. More eye-catching still, Mr Miliband whipped Labour MPs in favour of recognition for a Palestinian state.

Two weeks ago he took time off the general election campaign to give a speech on foreign policy at Chatham House. He defended the rule of law, international institutions and diplomatic engagement, adopting a kind of language that could never have been used by George W Bush or Tony Blair. Indeed Mr Miliband’s speech was a rebuttal of American exceptionalism, what has caused such chaos around the world over the last two decades.

The neoconservative movement has often been traced to a group of American Trotskyist intellectuals who abandoned their faith in Marxism in the 1960s. In Britain it is a more recent phenomenon. John Major’s government of the 1990s was a traditional Conservative administration, which would never have supported George W Bush’s subsequent adventurism.

Neoconservatism gained power in Britain with the election of Tony Blair, a left-wing leader, in 1997. It survived the departure of Mr Blair, gaining a second lease of life with the emergence of David Cameron as prime minister in 2010. If Ed Miliband becomes prime minister after today’s general election, his arrival is likely to mark an important break point in British foreign policy. It may bring a more nuanced approach to international relations.

He does of course support the state of Israel, but with a refreshing new emphasis on the obligation of the Israeli state to recognise Palestinian rights. He favours diplomatic initiatives over military methods, another sharp break with the British approach of the last 15 years. Ed Miliband’s Labour offers a completely contrasting vision of foreign policy to David Cameron’s Conservatives. This is not widely understood.

- Peter Oborne was British Press Awards Columnist of the Year 2013. He recently resigned as Chief Political Columnist of the Daily Telegraph. His books include The Triumph of the Political Class; The Rise of Political Lying and Why the West is Wrong about Nuclear Iran.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye

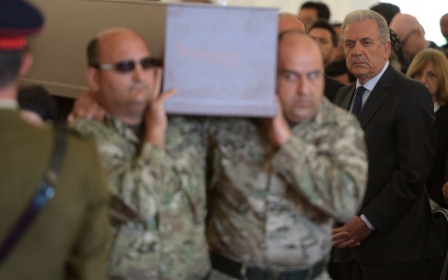

Photo: British Prime Minister David Cameron meets pilots, engineers and logistic support staff in front of a Tornado GR4 at RAF Akrotiri base (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].