FILM REVIEW: Godard's 'Here and Elsewhere'

CAIRO - “And then we came back home. I came back. You came back…We finally came back.”

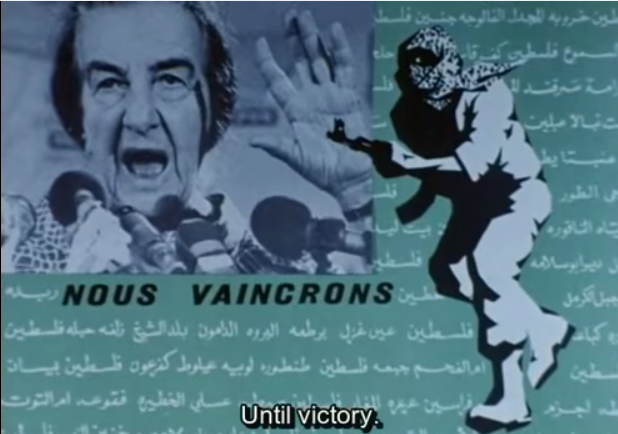

This is one of the first lines of Ici et Ailleuers (Here and Elsewhere), a 1976 documentary-treatise directed by French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard and made as part of the “Dziga Vertov Group” with Jean-Pierre Gorin and Anne-Marie Mieville.

The narrator-auteur is coming back from the front-lines of the Palestinian revolution; back to France and self-reflection. We have already seen the Fatah training camps and the young girls making uncertain karate-ish moves on a makeshift parade ground in the hills; we have seen images of poverty and barefoot children, countless feda’yeen reading newspapers and little red books with kuffiyehs wrapped around their heads, and a little girl bawling Mahmoud Darwish lines amongst the ruins of Karameh. Soon we will be watching a working-class family sitting in an apartment in France. They will be watching Palestine, more or less, on the telly.

Somewhere in the middle of the film’s journey back, to the “here” (France) from the “elsewhere” (the Middle East), lies a story of delays, fraught editing and hard-nosed graft; the real-life narrative of the making of Here and Elsewhere, which is as much a part of the film as the Brechtian stage-props, meandering commentary on film theory and radical politics, or the machine-gun fire that sporadically soundtracks it all.

Although it was finally released in 1976, Godard’s team originally set out at the start of the decade to document conditions in the Palestinian camps, as part of a PLO/Arab League-funded project under a different title, Until Victory. They spent months filming in Jordan, Lebanon and the West Bank at a turning-point in the history of the Palestinian revolution. The 1967 defeat had already happened. But Black September, and the beginning of the PLO’s devastating re-exile in Lebanon, had not. They are both palpably felt, about to happen.

However, as much a product of the events that rocked the Palestinian feda’yeen in the early 1970s, as a reaction to them, Here and Elsewhere ended up as a very different film. The end product is not a film about refugee camps. It is more a film about filming refugee camps.

Here and Elsewhere was screened last weekend as part of the “Hybrid Feels: Revisiting the Documentary” festival at Zawya, a downtown venue now cementing its reputation as Cairo’s one and only art-house cinema. The festival is the cinema’s “first curatorial tribute to non-fiction”, according to the programme, which means that over the next month Cairene audiences get to see timely, important documentaries like Les Chebabs de Yarmouk (2013) and Laura Poitras’ award-winning Citizenfour (2014), as well as sit in on anthropological discussions and workshops on documentary filmmaking.

Godard’s film is a good place to start then, because it is about making film and thinking about film as much as it is about Palestine and how we see it.

In the early 1970s, Godard came back to France with hours and hours of footage from his travels in the Middle East. But, after deliberations and indecision over the direction or content of the film, it stayed on the shelf. Watching it now, you can feel the presence of a frustrated (but equally reflective) filmmaker as he tries to piece something back together. “Nothing is going well anywhere,” the narrator-auteur says, and maybe he is speaking from Palestine or France or the cutting room. There are repeated meanderings about “chains of uninterrupted images … enslaving one another” - and Godard’s usually disorienting cutting and splicing of image and sound now feels doubly disruptive, like dull-clicking synapses frantically making their way towards an idea, or a sense of Brechtian verfremdungseffekt (“alienation”) that has crept into the film as much as the audience watching it.

After early and major successes in the mid-1960s - films like Breathless, for which he is probably best known - Godard is sometimes criticised for turning to overly political obscurantism towards the end of the decade, often by the sorts of people who say that art should not be political because art is art and politics is politics. One example from Godard’s period of “militant cinema”, which arguably support this slightly facile claim, might be Sympathy for the Devil, which splices documentary footage of the studio sessions that produced The Rolling Stones’ counterculture-defining record of the same name, with a series of jarring political allegories.

But Here and Elsewhere, although it is challenging to watch and could probably do with repeat viewings to really appreciate it, goes further. The main thing I walked away from Zawya with was a sense of Godard’s fallibility, something that is openly explored in the film. The argument is that this is also the fallibility of documentary, non-fiction, journalism.

It’s actually quite rare to gain a self-critical insight into how non-fiction like this is made. If you’re lucky, you might get a “story behind the story” text box in your magazine, or a “behind the scenes” extra on your DVD. But isn’t this often just as stage-managed or tidied-up, or at least moulded into a narrative, as the non-fiction itself? You are still being shown what to see, rather than just seeing.

Why did the journalist decide to interview this person? Why was he or she so attracted to this story, and what were they trying to say by communicating it to the audience? Are the subjects of the film representative of the story, or has the filmmaker chosen them for some prejudicial, political or other reason? Questions like these are often absent, while Godard’s film - in some way - tries to present them. We see the refugee camp, but after that, we see why we saw the refugee camp in the way we did.

One of the funniest parts of the film comes when Mieville, Godard’s then partner and co-editor, analyses the images he came back with from Palestine. She admonishes him for the overly performative shots of the girl reciting Darwish in Karameh. What about the attractive Palestinian woman speaking directly into the camera? Godard probably chose her because of her looks, Mieville says.

In Here and Elsewhere, the filmmakers are proving their point by criticising those who made it. Themselves.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].