In Egypt, thieves fall out

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has had two years of unlimited power and support to build a political base. During this time, he received $39.5bn in cash, loans and petrol derivatives from three Gulf States up to January last year. Since then, the figure may have risen closer to $50bn. If any leader had the opportunity to remake politics in his image, it was him.

Instead, the opposite has happened. The general turned president has been hemorrhaging support. The first to peel away were liberals who deluded themselves that the overthrow of Egypt’s first democratically elected president would lead to more democracy.

When Ayman Nour, founder of Ghad al-Thawra party, left Egypt after the coup (he recalls speaking to Sisi with one hand on the mobile and the other packing his suitcase ), Mohammed el-Baradei screamed at him for abandoning them in their hour of need. Weeks later, Baradei found himself doing the same thing. The vice president and founder member of the National Salvation Front left Egypt branded a traitor. The leaders of April 6 followed the Brotherhood to prison.

One by one, Sisi’s troops broke ranks. Some admitted they had been duped. Moheb Doss, one of the founders of Tamarod, the grassroots movement that allegedly collected 22 million signatures calling on Morsi to announce early presidential elections, admitted that they were used by military intelligence, Sisi’s power base in the army.

"How did we go from such a small thing, five guys trying to change Egypt, to the movement which brought tens of millions to the street to get rid of the Brotherhood? The answer is we didn't. I understand now it wasn't us, we were being used as the face of what something bigger than us," said Doss. "We were naïve, and we were not responsible."

By May of last year, Sisi had to bully, bribe and threaten voters for three days to turn up to the polls to vote for him. The millions of 30 June had vanished, never to return.

This internal bleeding has never been staunched. I wrote recently of cracks emerging among Egypt’s generals, some of whom had been talking with candour to colleagues in the Gulf. Last week, some of those cracks appeared on the front page of al-Shurouk newspaper, a government noticeboard.

Ahmad Shafiq, the candidate put up by the army to oppose Morsi at the presidential elections, was accused of trying to mount a coup.

“The security agencies have monitored the movements and communications of Shafiq, who resides in Abu Dhabi, with certain personalities in 'sensitive' places that continue to support him and work for 'destabilising' Sisi's legitimacy in the hope that Shafiq may become the president of the republic once a coup is carried out against the coup leader”.

No irony was intended. The government source quoted by al-Shurouk was candid about the extent of the internal challenge. Not only did the plot involve “security and political personalities ” - ie generals in the army and oligarchs - but officials from the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and the United States.

The coolness between the new King Salman and Sisi is a political fact, of which, more later. But the inclusion of the Emiratis in the list of anti-Egypt actors is new. If Sisi has indeed lost the support of Mohammed bin Zayed as well as losing Salman, he really is in trouble, because that is two of his three main donors. The Emiratis are supplying arms to Sisi’s covert intervention in Libya.

Just in case Shafiq did not take the hint, a further warning was issued the next day by Yousef Al-Husseini - the journalist described as “the boy” by Sisi’s men in the leaked tapes. Al-Husseini said the plot involved a Gang of Four. Shades of the Cultural Revolution? The four he named were Shafiq, Jamal Mubarak, General Sami Anan and Morsi himself, who is now on death row.

Both Shafiq, in denying the plot, and the television anchors like Amir Adib who joined the hue and cry, made the same point: "Weren't Shafiq's people standing by Sisi's side in the (2014 presidential) elections?" They were indeed. This is an internecine struggle conducted in public view among members of the same political and military clan. Shafiq and Sisi were at one time fellow officers. If ever there was truth in the maxim that thieves fall out, it is to be seen in Egypt right now.

In rebutting the claims, Shafiq’s lawyer Yahya Qadri insisted that Shafiq did receive a telephone call on the eve of announcement of the presidential election results from Sami Anan, the former Chief of Staff, congratulating him on winning the presidency.

A fifth member may have joined the gang. Naguib Sawaris, Egypt’s third richest tycoon, a Copt, and staunch opponent of the Muslim Brotherhood, has come under intense public criticism from pro-Sisi television commentators, who have accused him of having US nationality and that his loyalty to the country is now in question. Sawaris’s “crime” is his attempt to create a coalition that will run for the prime minister’s job.

This is still a sensitive post for Sisi, because under the existing constitution, it retains significant power. It is what is stopping him from holding parliamentary elections. If he did, the position of defense minister would still be immune from presidential control. Of course, this was a provision inserted to protect Sisi himself, when he was defence minister under Morsi.

Tahani al Gebali, the former constitutional court member, admitted as much when she said Sisi wanted to remove this provision from the constitution. Sisi is caught in a web of his own making.

I understand that Sisi has already tried once to remove his current defense minister, Colonel General Sedki Sobhi, and failed. If Sisi wishes to pursue this course, the only thing left is for Sobhi to lose his constitutional immunity. The general may not be alone in his concern for the direction Sisi is taking his country. I am told that half of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), are voicing similar concerns.

If this is true, the internal problem for Sisi - with unrest in both SCAF and with big business close to the Coptic Church- is looming as large as the external one. Back to Saudi Arabia.

On Sunday, another article appeared in al-Shurouk, warning Salman that he had crossed a “red line” in arming Islah - a Muslim Brotherhood linked political group - in Yemen. The article claimed: “According to one of those who spoke to Al-Shurouk, 'Saudi Arabia itself, and despite the tight internal security policy, may find itself facing a new predicament associated with the Brotherhood – just like the rest of the Gulf states. And in this regard we have been talking to our brothers in the United Arab Emirates in an attempt to raise the issue quietly within the framework of the Gulf Cooperation Council.'”

It does not stop there. Not only has Riyadh become closer to Islah in Yemen. Saudi Arabia is no longer talking through intermediaries with leading members of the Egyptian opposition. My information is that there have now been meetings between secular and Islamist Egyptian leaders in exile and associates of the Saudi royal court. That included the Muslim Brotherhood. No conclusions were reached, but a dialogue has been set in motion.

There are other hints too of a change in Saudi thinking on the Brotherhood. The Saudi Minister of Islamic Affairs Salih Al Al-Sheikh was quoted by the London-based newspaper Al-Ahdath saying that displaying the Rabaa symbol was no longer considered a crime. He said some of the people who sympathise with the Muslim Brotherhood only do so as an expression of opposition to the destruction and murder that took place in Cairo in August 2013. For this reason, he said it is mandatory to be fair and thorough when judging the sympathisers.

When the former King Abdullah banned the Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation in the Kingdom, thousands of Saudis had to take the Rabaa symbol down on their twitter accounts or face prosecution as Brotherhood sympathisers. Now the symbol itself has been rehabilitated in the kingdom.

If Sisi wants to appeal to his “brothers in the GCC”, he had better be quick. He has few of them left.

- David Hearst is editor-in-chief of Middle East Eye. He was chief foreign leader writer of The Guardian, former Associate Foreign Editor, European Editor, Moscow Bureau Chief, European Correspondent, and Ireland Correspondent. He joined The Guardian from The Scotsman, where he was education correspondent.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

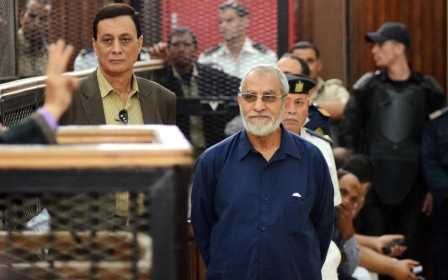

Photo Credit: Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi stands on stage on the opening day of the World Economic Forum on the Middle East and North Africa 2015 on 22 May in the Dead Sea resort of Shuneh, west of the capital Jordanian Amman (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].