Defiant Erdogan faces elections

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is used to winning handsome majorities in elections that politicians dream of in other countries. Last August he became the first-ever popularly elected president of the Turkish Republic with 51 percent of the votes. A few months earlier, Turkey’s ruling party, the AKP, or the Justice and Development Party, took 43 percent of the votes in the March 2014 local elections. This was down from the 49 percent of votes it won in the 2011 elections, but was still nearly 17 percent ahead of its nearest rivals.

Though no one doubts that Sunday’s general elections will see the AKP emerge well ahead of its rivals, this might not spell a real political victory. This is because AKP is campaigning not just to win a simple majority in the National Assembly but for a much harder goal - a parliamentary mandate to convert Turkey into a presidential republic in which most executive power will rest with the head of state. Erdogan believes that Turkey’s parliamentary system has been holding the country back. To achieve this, he ideally needs a two-thirds majority in parliament, something the AKP very nearly achieved in its first parliament but which has receded steadily in subsequent polls.

Though he is not explicitly campaigning for his former party, President Erdogan has toured the country tirelessly over the last month, speaking to huge rallies that do not directly mention the campaign - they are not called "meetings" but "gatherings" - but convey the message that a strong and prosperous Turkey depends on re-electing the AKP. Initially, the president spoke of winning 400 out of 550 seats. But that never looked likely and the tide of public opinion now seems to be ebbing.

It would be wrong however, to underestimate the strengths both of Erdogan’s personal appeal to conservative voters and the organisational strength of the AKP.

Since his early years as mayor of Istanbul (the office that propelled him to national prominence) Erdogan has been a very effective organiser. Even when there is not an election campaign going on, the AKP is run with almost military precision, its deputies being fed constant instructions over their phones and summoned to regular weekend briefings with the leadership. It is thanks to this that despite the rupture with its former allies in the Gulenist movement in 2013-2014, the AKP’s parliamentary contingent only lost about a dozen MPs of the 326 seats it won in 2011. Its candidates this time will also have been selected for their loyalty.

Erdogan’s organisational skills and those of the AKP’s managers can be seen in the rallies. These feature giant crowds (the AKP claimed two million at the president’s meeting at Yenikapı in Istanbul on 31 May, though this was certainly exaggerated), a sea of flags, cheering people and fierce enthusiasm, even if perhaps these occasions are somewhat orchestrated.

Even in Bingol last Wednesday, an ultra-conservative town in southeastern Turkey, Erdogan was greeted by a large crowd. All his skills and the force of his rhetoric were in play. He held up a Kurdish translation of the Koran, reminded his listeners of all that he had done to help the Kurds to have a recognised public place in Turkey’s life, pledged that he would continue to do so. He also lashed out against the Kurdish-rooted Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), though he did not name it, accusing it of links with the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) and of "terrorism" and of being hostile to religion. He warned that there were people thinking of having the call to prayer in Kurdish, and said that the Armenian lobby, homosexuals and atheists were among the "representatives of strife" linked with HDP.

Uncompromising as discourse of this kind is, it signals to tens of millions of Anatolian religious conservatives that President Erdogan is their man - and those millions include many Kurds in eastern Turkey where the AKP is locked in a two-party contest with the HDP and the Kurdish nationalists. It is the reason why the political map of Turkey in the last three general elections shows the AKP heavily dominant across almost all of Turkey, barring some provinces in the southeast where Kurdish nationalism is strongest and on the western and southwestern seaboard fringe where the centre-left still hold out.

Despite President Erdogan’s constant emphasis on a religion-based "unity", however, and the absence of energetic, well organised opposition parties, the AKP seems to have a nationwide ceiling of about half the electorate in the staunchest provinces. It is this reality, and Turkey’s proportional representation system, which makes the president’s dream of a two-thirds majority apparently unattainable.

That goal has slipped even further away with the unexpected appearance of a strong new opposition party from among the Kurds that appeals also to the left-of-centre vote nationally. Despite the obstacles to the emergence of major new parties in Turkish politics (not just the well-known 10-percent barrier, but also formidable branch requirements and no access to the enormous state subsidies that the established parties enjoy), the HDP looks poised to enter parliament. If it were to win the 12 percent suggested by the final opinion polls, the HDP could have between 60 and 80 seats in the new parliament and the AKP might be hard put to obtain an overall majority.

Erdogan’s response to challengers is always defiant and uncompromising, perhaps because he sees them as threats to his hopes for a resurgent Turkey, heir to its Ottoman past, a land religiously conservative, but economically strong, even producing its own airplanes. He and the prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, have hurled the strongest possible accusations against their opponents in other parties and the press. It appears to him that opponents inside Turkey and outside are conspiring to fell the AKP.

Last week Erdogan personally launched proceedings against a left-wing editor who published claims the government had sent arms into Syria, denouncing him as "a spy and an agent", and seeking a double sentence of "aggravated life imprisonment". This may please AKP conservatives but does nothing to win marginal votes. Against an increasingly difficult economic background, an election which should be an effortless victory – no poll has predicted less than 38 percent of the votes for the AKP, and most have been over 40 percent - could turn into a political setback. In that case, Erdogan would remain dominant but have few potential allies outside his party to work with.

- David Barchard has worked in Turkey as a journalist, consultant, and university teacher. He writes regularly on Turkish society, politics, and history, and is currently finishing a book on the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

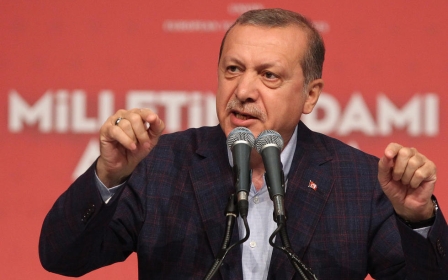

Photo: File photo shows Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].