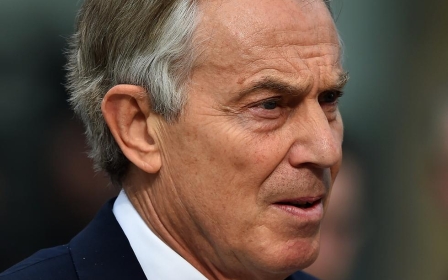

Why Tony Blair is talking to Hamas' Khaled Meshaal

The revelation that Tony Blair and his officials are in active negotiation with Khaled Meshaal, the leader of Hamas, to bring about an end to the eight-year siege of Gaza might come as a surprise to those acquainted with the record of the former Middle East envoy.

Blair has provided invaluable international cover for Israel’s actions; he remains an outspoken supporter of the military coup in Egypt; and has ideologically positioned himself as the nemesis of Islamists of any colour.

Not many politicians would have turned up to Ariel Sharon’s funeral and said the following of the former commander of Unit 101 responsible for the massacre of 42 villagers in Qibya, or the defence minister who invited Phalangist forces into the Sabra and Shatila camps in Beirut: "The state, from which the age of 14 he fought to bring into being, had to be protected for future generations. When that meant fighting, he fought. When that meant making peace, he sought peace."

Even recently, Blair made little secret of his ambition to unseat Hamas. In rejecting the military option, he suggested the same ends could be achieved through other means: “There won't be a destruction of Hamas ... you won't destroy Hamas as a political entity...what I do know is that will only happen if it happens within the context of a way forward, particularly for the people of Gaza, that gives them some hope for the future, because in the end a political movement like that has support on the ground, and you need to shift ... take away that support."

So why are these talks taking place at all, and why now?

The first place to look for evidence of a rethink about the eight-year-long siege of Gaza is Israel’s security establishment. It has fought three wars in that time. That is not to count smaller incursions, bombing raids and targeted killings.

Hiroshima's worth of TNT

Israeli forces dropped an undeclared amount of TNT on Gaza from the sea, land and the air in the 50 days of the last war. The tonnage used at one point on Rafah was so great that even the Pentagon recoiled and refused temporarily to open up its arsenal of guided bombs to replenish Israel’s stock. The head of the Palestinian bomb squad claimed, before he was killed, that the total amount of explosive used on Gaza was between 18,000 and 20,000 tonnes, the equivalent of the Hiroshima bomb. The IAF itself admitted dropping 400 tonnes in two days alone.

This blitzkrieg has only strengthened Hamas’ military capability over the years. It has developed, and continues to test, rockets with a range covering much of Israel. This leaves Israeli military planners with only one option, a full occupation of Gaza. But that would not be straightforward.

It would entail heavy loss of civilian life and high Israeli military casualties in urban warfare. It would mean resuming responsibility for Gaza’s devastated population and the outcome of such a war would be unpredictable.

Hamas remains, along with Hezbollah, Israel’s most active enemy. It can not challenge Israel’s military might, but it has managed to create a rudimentary army on the land of Palestine itself, and there continues to be a strong camp within Israel, headed by Avigdor Lieberman, that presses for its complete elimination.

But another camp in Israel exists which sees chaos as a greater enemy.

They argue that it is better for Israel to have Hamas controlling Gaza than the Islamic State or its affiliates. This idea is not new. Two years ago, the head of the IDF’s Gaza Command, Brigadier-General Miki Edelstien said that Hamas was acting as Gaza’s policeman: “Hamas leaders, both military and political, are doing everything to maintain restraint. One of their most important brigades is now acting as ‘border police,’ with 800 combatants taking shifts preventing all sorts of tiny organisations that want to fire rockets or place roadside bombs [on the border].”

The same idea has resurfaced in a column by Mossad’s former chief Efraim Halevy, who called Hamas Israel’s “frenemy”: "Hamas, for example, is in a state of war with Israel, while its battle against other organisations in the Gaza Strip, which reject its authority, serves Israel's security needs.

“If the recent talks mature into an agreement between Israel and Hamas for a limited period of time, it will be necessary to turn it into the first stage of taking a new road. The tactic must lead to a strategy of an ongoing dialogue. The strength of every agreement will always depend on the relations between Israel's citizens on this side of the border and the Arabs on its other side. An official source was quoted recently as saying that we have calm even without giving the Palestinians in Gaza a seaport and an airport. Without addressing these two ambitions, the recent talks prove that the 'calm for calm' formula is outdated. Such an approach guarantees another round of fighting."

Powder keg

The third ingredient is the prospect that if nothing happens to change the current status quo, Gaza could be the epicentre of an uncontainable explosion.

This is what Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the German Foreign Minister, meant when he said recently that Gaza was a powder keg : “I came out of all my discussions yesterday in Jerusalem and in Ramallah with the hope that all parties are mindful that we are sitting on a powder keg here and that we must ensure that the fuse does not catch light,” Steinmeier said on June 1.

The prospect of a security meltdown in Gaza, of Hamas losing its ability to restrain other armed groups in its territory, does not appeal. With the proximity of jihadi groups in Sinai swearing allegiance to IS, and the battle going on around Damascus on Israel’s northern border, the prospect of Gaza disintegrating into small, undisciplined but heavily armed groups of militants presents a major security risk to Israel.

For the EU, which has recently been forced to revise its measures to pick up migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean from Libya, a major explosion in Gaza could force an exodus of hundreds of thousands of civilians. Neither Israel nor Egypt would accept them. They would literally be pushed into the sea.

A fourth element in these calculations could be the possibility that Hamas still holds Israeli military prisoners. There is the story of the Israel-Ethiopian citizen who crossed into Gaza after the war and was detained there. As Richard Silverstein reported, Hamas put up a billboard which featured images of Oron Shaul, an Israeli soldier, whom Israel claims was killed during the war. Shaul is behind bars on the billboard, indicating that Hamas claims he is alive. Steinmeyer himself was thought to be negotiating the return of the remains of Shaul and Hadar Goldin to Israel.

No deal to end the siege is yet on the table or even close to being signed. The negotiations between Blair and Meshaal have taken their time for two reasons: there is much suspicion of Blair’s motives in acting as go-between. His involvement with the Emiratis and the Egyptian authorities have not gone unnoticed in Gaza City.

Avoiding the Fatah trap

More substantively, Hamas does not want to be seen as treading in Fatah’s footsteps after it recognised the State of Israel. Hamas does not have to recognise Israel nor indeed decommission its armed forces, to secure an opening of the borders. It merely has to agree to and maintain a ceasefire, which is what it is already doing.

But nor can it sell the resistance to Israel’s occupation for pallette loads of bananas and pasta. That is short selling. Palestinians have a painful collective memory of two decades of peace negotiations, which allowed 600,000 settlers to establish their own facts on the ground in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

This time a ceasefire must lead to tangible political as well as physical gains for Palestinians in West Bank and Gaza alike. If what we are seeing are the first steps of Hamas being brought in from the cold, its strategic challenge is to achieve liberation from occupation for all Palestinians without compromising the founding principles of this conflict such as establishing the right of return. Its not just a principle or a distant memory. Just remember where Gaza’s population came from. It is a population of refugees.

The British involvement in the Doha talks could yet backfire on Cameron. He is sitting on a report by Sir John Jenkins which concludes that the Muslim Brotherhood is not a terrorist organisation. This has not stopped ministers in the government from attempting to conscript this report as the basis for a declaration that the Brotherhood is an extremist organisation which endangers the social fabric of Britain. They after all have links with Hamas.

Cameron will be hard put to publish a proposal which argues that the Brotherhood’s influence in Britain should be monitored and curtailed, if a former British premier is talking - with Cameron’s full knowledge and authority - to the leader of Hamas. The release of the Jenkins report could have a bad impact on the dialogue Cameron is trying, through Blair, to foster with Hamas.

- David Hearst is editor-in-chief of Middle East Eye. He was chief foreign leader writer of The Guardian, former Associate Foreign Editor, European Editor, Moscow Bureau Chief, European Correspondent, and Ireland Correspondent. He joined The Guardian from The Scotsman, where he was education correspondent.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo caption: Middle East Quartet envoy Tony Blair (2nd from R) visits a UN-run school sheltering Palestinians, whose houses were destroyed by what they said was Israeli shelling during the 50-day war last summer, in Gaza City on February 15, 2015 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].