Egypt’s campaign of elimination continues, violence and instability loom

Egypt’s military-backed government is on a mission to completely eliminate the Muslim Brotherhood from Egyptian political and social life. It’s not as though additional evidence of eliminationism was needed, but Egypt’s government provided it on Wednesday when it killed 13 members of the Muslim Brotherhood as they gathered in a private home, reportedly over how to distribute money to orphans.

Earlier in the day, ISIS launched an attack against Egyptian military posts in the Sinai Peninsula, killing dozens of Egyptian soldiers. The MB quickly denounced the killings, while ISIS - which considers the Brotherhood apostates - claimed responsibility. The Egyptian government’s decision to go after the Brotherhood members was absurd, but not at all surprising.

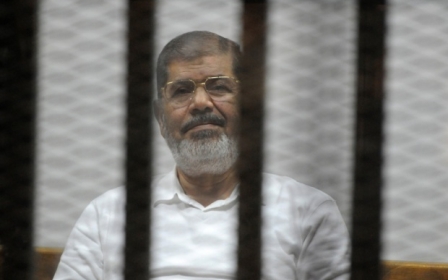

The Brotherhood represents one of the greatest threats to the Egyptian military, police and judiciary, each of whom has enjoyed immense privilege and a relative lack of public accountability for the better part of six decades of military dictatorship. In Egypt’s brief 2011-2013 transition to democracy, the MB swept five consecutive elections, including the 2012 presidential election that brought Mohamed Morsi to office.

Most of the elections were landslides and there was no serious indication that the Brotherhood could have been defeated at the polls in the short term. Although the Brotherhood did not perform well while in office, the mere threat of elected governance - represented by the MB’s successive electoral victories - demonstrated the extent to which Egypt’s state institutions could, over time, lose influence.

During Egypt’s brief flirtation with democracy, the Egyptian military, police and judiciary came out losers. Police were tried and sentenced after a democratic fact-finding committee provided evidence they were responsible for killings in Port Said; high-level military officers were implicated in a fact-finding committee assembled by the elected president; and the work of the judiciary was placed under greater scrutiny.

These measures of accountability were implemented before Egypt had even been provided a complete stable of democratic institutions. Had Morsi’s plans for parliamentary elections come to pass, Egypt would have had, for the first time in its modern history, a meaningful balance of power - the now defunct 2012 Egyptian Constitution decreed a prime minister who constitutional law experts said would have been as powerful as the elected president.

It is perhaps not difficult to see, then, why Egypt’s largely corrupt police force celebrated Morsi’s removal. In a speech delivered shortly after the coup, a police general told officers that the days of humiliating police officers were over. He said, “What used to happen is done and not going to occur again.” He went on to tell the officers that “no one will be able to stand against us.”

Even with an elected president, there were still numerous problems with Egypt’s fledgling democracy. Over time, however, political pluralism and competition (there were more than 40 registered political parties by the time Morsi was ousted in July 2013) would have ensured greater accountability for all of Egypt’s political actors. Hopes for more accountability were dashed when the military removed Morsi from office on 3 July 2013, just one year into his four-year term.

What the military-backed government did immediately after the coup was telling. On the day of the coup, the elected president and his entire presidential team were kidnapped; arrest warrants were issued for hundreds of Brotherhood leaders; a new discourse suggesting the Brotherhood was “treasonous” began to crystalise; and all media outlets sympathetic to the Brotherhood were shut down.

In the weeks and months after the coup, the newly cemented government carried out several large massacres of mostly unarmed Brotherhood members and supporters, arrested tens of thousands of Islamists on political charges, formally banned the Brotherhood’s political party, passed legislation preventing individual MB members from running for office as independent candidates, and issued the largest mass death sentences in modern world history. Additionally, the Egyptian government has banned books written by Brotherhood religious scholars and frozen the funds of Brotherhood-operated charities. The government has also cracked down on secular opponents of the military order.

In summer 2013, political scientists and other analysts correctly predicted that Egypt’s coup would produce repression and instability. As all avenues of dissent have been shut off and Islamists told in clear terms that they will not be allowed to participate in politics or have any say in Egypt’s sociopolitical existence, ISIS has stepped in as a major force.

Terrorism has spiked dramatically in Egypt since summer 2013 - hundreds of police and military personnel have been killed in dozens of attacks - and Egypt has become a hotbed of terrorist recruitment. Although the Brotherhood continues to preach a predominantly peaceful line, evidence suggests that they are having difficulty convincing some younger members and supporters of the need to remain peaceful. Reports indicate that a small number of Brotherhood youth may have already left the group and embraced ISIS’s violence doctrine. Moreover, Wednesday’s violence against Brotherhood members could prompt the MB to abandon peaceful resistance altogether.

Professor John Esposito wrote in July 2013 that “The [Egyptian] military’s purpose is transparent and in line with the modus operandi of Mubarak for decades: use brute force to intimidate, repress, and provoke the opposition to violence and then say, ‘Look I told you they were wolves in sheep’s clothing’.”

A cryptic Wednesday statement by the Brotherhood seems to suggest that the group may be shifting from peaceful to more violent resistance. The statement referenced a “new phase” to account for the impossibility of “controlling the anger of oppressed people who do not accept to die in their homes in front of their families”.

With Sisi’s government demonstrating that it is not capable of stopping vigilante violence even in heavily secured areas - on Monday, Egypt’s prosecutor general was assassinated in a heavily guarded section of Cairo - Egypt may be headed for an unprecedented violent abyss. The victims, then, would not only be the moderate Islamists who have been killed and arrested en masse for two years, or Egyptian soldiers simply carrying out mandatory duties, but everyday Egyptians simply trying to live their lives.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].