BOOK REVIEW: Yusif Sayigh: Arab Economist, Palestinian Patriot

Rosemary Sayigh will always be remembered for her prescient book, Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries: A People’s History (Zed, 1979/ 2007), written as a result of her prescient 1970s interviews with residents of Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. Using contemporary technology – audiocassettes – she gleaned privileged insights into these exiled communities’ post-1948 and post-1967 traumas. In this, her late husband’s place in history, she’s selflessly kept the lowest profile possible.

Rosemary married the politically active economist Yusif Sayigh in 1953. Through years at the American University in Beirut, he was the only financial expert in town in the Palestinian rights movement, with a good organisational sense too. This kept him essentially overworked as his life was one of two jobs. In the early 1980s, during a period of recovery from open-chest heart surgery, his academic wife and partner recorded what is most of this book.

So, 20 hours of spoken recollection results in some extraordinary micro-history of his youth that manages to convey how things were, without him being the central focus. Although personal, with both pride and regret, Yusif’s life story is a series of windows to see Galilee and Tiberius as they once were. Fascinating pages point us to clothing, village drinking and gambling, forced mobility due to the British Mandate occupation, a free trade agreement between Palestine and Lebanon, co-operative ownership of local buses, and more surprises.

One disadvantage of such a non-biography is the lack of frequent criticism. Indeed, Yusif is routinely praised for everything from his humility and sensitivity to his talent for management. Still, if you can manage to be married to someone for half a century and emerge singing his praises, there’s got to be a lot that’s praiseworthy.

Ever attempting objectivity, the Syrian Liberation (PPS) and pan-Arab emancipation are compared, with the former being intellectually hijacked by Antoun Sa’adeh as almost a cult, what Sayigh calls “Syrian Soul”. Therefore, the Arab’s music became Syrian music. Yusif, the clear-thinking witness, repeatedly reminds the reader that, back in the day of the post-Great War carve-up of former Ottoman areas by Britain and France, Palestinians thought of themselves as Arabs. Palestine’s cultural and topographical links to Syria were politically, realistically severed when Paris claimed Damascus.

The Jewish communities are observed sociologically, archly separating themselves from the Christian and Muslim communities under the pre-Israel, British Mandate decades. In these scenes, it’s not hard to see the Zionist Jews as taking the same roles as Hitler’s so-called Aryans, with Arabs cast as the dehumanised vermin.

Even the misunderstood Mufti, Hajj al-Husseini, is rationally analysed. Yusif knew him for some years after the Mandate Government had forced the religious liberator’s exile. So it’s speculated that, on one hand, the by then roaming Mufti was a weak organiser, but, on the other hand, he might not have wanted a large political movement that wriggled out of his own control.

Mr Sayigh was manager of a Tiberian hotel during the war years 1943-1944, when the singing film star Asmahan stayed while working undercover to get Druze co-operation with British forces. Sayigh was also diligent in trying to block land sale to the Jews. When an internationally induced, two-state solution was being slapped onto the front pages, he wrote the Arab Land Hunger Report, classifying dunums not just by their flat map measurement but also by their agricultural worth. He ran the Arab National Treasury, which, like the Arab Higher Committee, meant Christian and Muslim Palestinians.

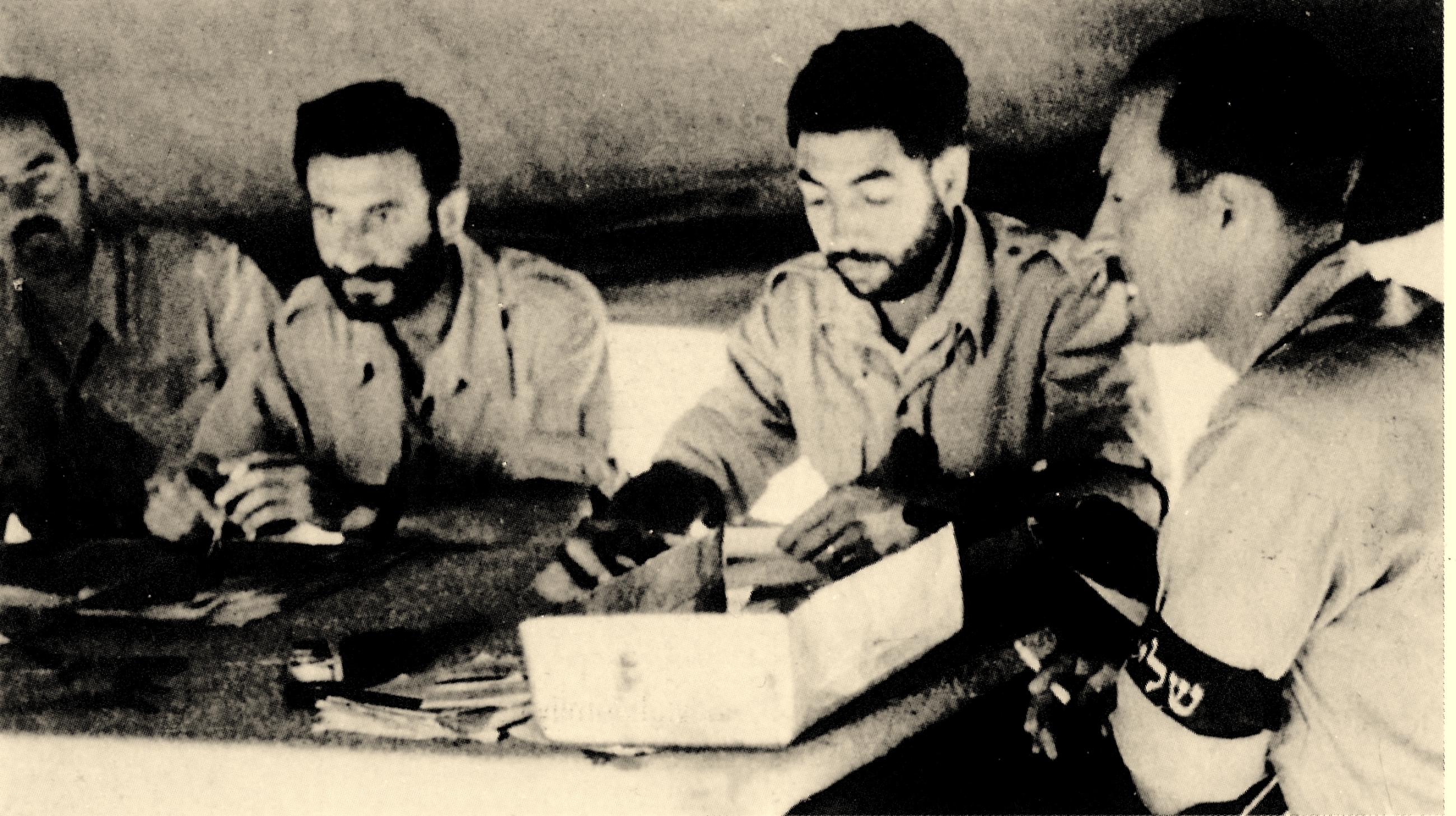

The immediate period before the Nakba is detailed as a kind of de facto Israeli garrison era, with settler checkpoints, as the British were reduced to either reacting or packing-up. He likens it to “Beirut in the civil war.” Palestinian efforts at armed defence were comparatively weak, as Yusif tried in vain to raise the necessary funds. In 1948, he became a prisoner of war.

He soon emerged as an economics expert, spending more than two decades in professorship at the American University in Beirut (AUB). One fascinating account deals with one of his many economics papers. Well respected in the region as well as by such American establishment bodies as the Ford Foundation, he debunked the myth that Muslims couldn’t be entrepreneurs. This had been touted by an Israeli economist who mistranslated the Qur’an.

A generation later, the birth of the PLO is detailed as part farce. The author’s role was always a supportive one, providing quality advice to their planning centre for three crucial years (1969-1971), sometimes at risk to his own life and certainly to his bank account. Imagine a husband and father working half-time, at half-salary, and then taking a full year of leave at no pay. And all for the cause.

All I’d known about Yusif Sayigh was his post-Oslo argument with Yasser Arafat over the latter’s alleged misappropriation of millions of dollars, and, more importantly, insistence on being the sole authority of World Bank development money. If the weakest point of these memoires is the post-Nakba years, the creation of the PLO is unpacked with insight, and, even better, there’s a detailed dissection of the Palestinian incompetence in using the USA and EU financial incentives that were intended to make Oslo a success.

Somehow, this economist managed to balance the books between his personal desires and political goals by refusing payoffs, grade promotions and privilege. So he wasn’t about to watch his mouth; they could all just watch inconvenient truths leap out of it.

Sayigh and others may have gone on holding Abu Ammar (Arafat) in their hearts, but that didn’t change the fact that the beloved leader had messed up big time and been a victim of his own importance. To be fair, he and the PLO still worked together, even though they’d let his development plan gather dust on the shelf (similar advice to Kuwait went ignored).

Still, he was seemingly always consulted for his brain and was too admirable to be dismissed. Perhaps Yusif was the only PLO thinker to not only challenge the leader, but let some hot air out of the leader’s balloon too: “I argue things out with Abu Ammar himself, or with people even more important than Abu Ammar [ouch!]. I will never relinquish my right to argue.” Sayigh’s unpacking of this drama is worth the price of the book alone.

Arab Economist is a conversational session and, if you keep this in mind, it’s a privileged read indeed. You’ll be glad to feel that you’ve known him.

Yusif Sayigh: Arab Economist, Palestinian Patriot – A Fractured Life Story, edited by Rosemary Sayigh is published by American University in Cairo Press, 388pp, February 2015 (ISBN 978-9774166716, 977416671X) £30/$45

- Andy Simons is a London-based retired book curator of modern UK publications for the British Library, who works with Palestine Solidarity Campaign branches, the Palestinian Return Centre and CADFA. He organised the 2014 Tottenham Palestine Literature Festival and has edited Palestine: The Reality, the 1939, Balfour-related work by JMN Jeffries, for republication in 2016.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].