Cameron’s mixed message on extremism and democracy

Throughout his premiership David Cameron has made a habit of delivering his most significant pronouncements about British Muslims when outside Britain.

The famous speech on “muscular liberalism” was delivered in Munich. Last month he escalated his rhetoric about what he likes to call “non-violent extremism” at a meeting of security experts in Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia. The prime minister’s weekend pronouncements about ISIS were made on television in the United States.

To make matters even worse, Mr Cameron’s choicest remarks about Islam at these events have often been shown in advance to newspapers with a record of stigmatising British Muslims, above all the Murdoch press.

The primary effect of his various international pronouncements has therefore been to strengthen the prejudices of those who already dislike or are suspicious of Islam. This approach has sent an unmistakable message out to British Muslims that his government is interested in lectures, but not dialogue.

This message has been reinforced by David Cameron’s systemic failure to pay serious attention to mainstream Muslim voices. Incredible to relate, he has entered a mosque only once during the five years of his premiership. This is a wretched record from a prime minister who has repeatedly claimed that he cherishes British minorities.

The prime minister’s speech on Islam yesterday took place in Birmingham. The decision to locate himself in Britain was in itself was a major step forward. It should be welcomed in other ways. The prime minister explicitly recognised that there is no contradiction between Islam and British values.

This is a statement which will disappoint some of his Conservative supporters, who have been arguing with increasing confidence that loyalty to the British state cannot be reconciled with Muslim faith.

Cameron even gave something close to an acknowledgement that Muslims can be subject to Islamophobia: “We should challenge together the conspiracy theories about our Muslim communities too and I know how much pain they can cause.”

In general, however, the prime minister’s analysis remains so flawed that it is fair to call it delusional. Like Tony Blair before him, the prime minister is either unwilling or unable to come to terms with the proven links between Western foreign policy and domestic terrorism.

This failure is especially baffling because the intelligence officials who advise the prime minister have for many years been crystal clear that a link exists.

For the prime minister, the problem has very little to do with facts. In fact, it boils down to just one concept which he calls “Islamist extremism”.

There are huge intellectual problems with Mr Cameron’s analysis, and he did not even begin to solve them in yesterday’s speech.

The first problem concerns definition. Mr Cameron thinks that extremists entertain “ideas which are hostile to basic liberal values such as democracy, freedom and sexual equality”.

According to this definition, Tim Farron, the newly elected Liberal Democrat leader who has problems coming to terms with gay marriage because of his Christian faith, is beyond doubt an extremist.

So are devout believers in most if not all of the world’s religions. Mr Cameron promised that a counter-extremism bill will be published when parliament returns from its summer recess. As matters stand his proposed legislation is a conceptual shambles.

But there is an even bigger problem for the prime minister if he wants anyone to take yesterday’s remarks seriously. This concerns consistency. The prime minister lectured Muslims yesterday (Why is it only Muslims, and not members of other faiths, who get spoken to in this way?) that they must abide by the liberal values of free speech, democracy, sexual equality, tolerance etc.

This is well and good. However, Muslims are surely entitled to expect that the British state itself honours and respects those vital qualities. It assuredly does not do this when it comes to foreign policy, and especially not when that foreign policy concerns Muslim countries.

Let’s take the crisis in Egypt, where the Cameron government has quietly endorsed the military takeover which ousted Mohamed Morsi, the democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood president. British ministers are so frightened of upsetting the bloodstained junta that now rules the country that they won’t even use the term coup d’etat to describe what happened.

Since the military takeover free speech has been suppressed with quite exceptional brutality. Thousands have been murdered by the state for protesting against an illegal regime.

David Cameron’s response? He’s invited General Sisi on a state visit to London. This visit is scheduled for later this year, and indeed is likely to happen at roughly the same time the British prime minister unveils his counter-extremism bill.

Saudi Arabia is another case in point. Here is a state which doesn’t know the meaning of free speech, which beheads its citizens, tolerates forced marriages, defines political opposition as terrorism, and arranges the persecution of homosexuals (last year a Saudi man was sentenced to three years in jail and 450 lashes after he was caught using Twitter to arrange dates with other men: a married man found engaging in homosexual acts can be stoned to death). Yet David Cameron treats the Saudi Arabia as one of our closest allies.

This means that the British prime minister is simultaneously sending out two diametrically opposite messages to a confused Muslim youngster in Bradford contemplating joining ISIS.

His system of international alliances makes the unambiguous statement that it is ok to behead, to torture homosexuals, to kill your opponents without trial, to force women into marriage.

At home, however, Mr Cameron lectures Muslims that such conduct is extremist, and warns them about entering what he calls a “pathway” to violent terrorism.

The contradiction between the prime minister’s support for democracy in Britain and dictators in the Middle East is very dangerous. Al-Qaeda and ISIS thrive on it. They use the contradictions embedded in David Cameron’s argument to argue that protestations that the West believes in liberal democracy are cynical and false. They have a strong point.

There is some good sense in the prime minister’s speech. It is an improvement on recent efforts. However, if the prime minister genuinely believes his own rhetoric that the fight against ISIS is the challenge of our generation, then he needs to think again

His assertion that there is no meaningful link between British foreign policy and domestic terrorism is laughably false. Mr Cameron urgently needs a new analysis if Britain really is to combat Isis.

- Peter Oborne was British Press Awards Columnist of the Year 2013. He recently resigned as Chief Political Columnist of the Daily Telegraph. His books include The Triumph of the Political Class; The Rise of Political Lying; and Why the West is Wrong about Nuclear Iran.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye

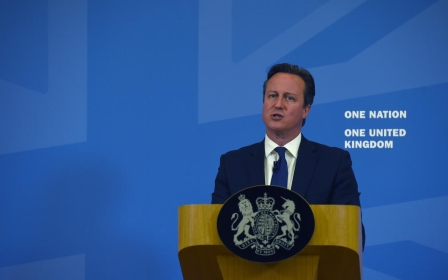

Photo: British Prime Minister David Cameron attends a ceremony offering condolences to new King Salman on January 24, 2015 at the Diwan royal palace in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, a day after the death of King Abdullah. (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].