Fighting for a future: Libya’s new generation of boxers

Libya's boxing coaches are determined to keep the rediscovered sport alive, training new fighters armed not with guns but with fitness and fists

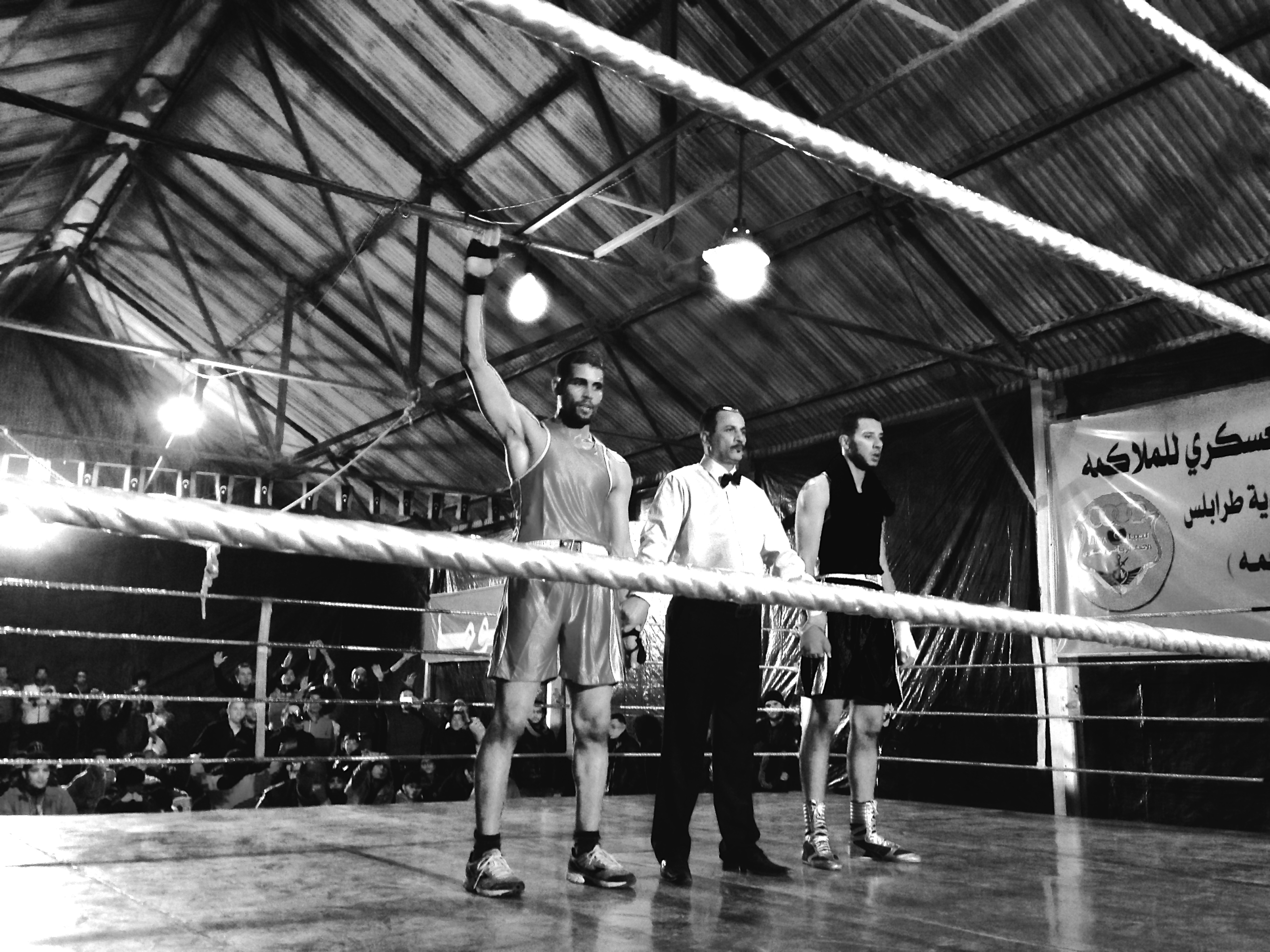

Usama Mohamed Maghboub after winning a local tournament in Tripoli (MEE/Tom Wescott)

Published date: Vendredi 28 août 2015 - 14:24

|

Last update: 9 années 3 mois ago

TRIPOLI - Former boxing Champion of Africa Mahmoud Boshkewa washes down the wooden floors of a gym in a dilapidated stadium in downtown Tripoli, in preparation for the evening’s training. Banned for more than 30 years under Muammar Gaddafi, who termed the sport “savage behaviour,” the 2011 revolution was a chance for boxing to finally make a comeback and Mahmoud was one of the country’s former greats who seized the chance to train a new generation of enthusiasts.

“We got in here two days before they killed Gaddafi and then opened the club on 11/11/11,” Mahmoud explains, proud of the memorable date. There was only one punchbag, formerly owned by Saadi Gaddafi - the sport-obsessed son of Libya’s long-term leader Muammar Gaddafi - who had closed the colonial-era stadium to the public, claiming it as his own personal sporting arena. “We had two more punchbags made by a tailor from an old parachute,” he said. “And that’s how we started, with three bags and 14 people.”

Nearly four years later, Ittihad Boxing Club has become one of Libya’s most successful clubs, where its most committed 50 members train six nights a week. On the evenings when downtown Tripoli is plunged into darkness during the daily power cuts now customary in Libya, they train by the light of torches.

Three of Ittihad’s young fighters have already won medals at international competitions, although two now live abroad, where opportunities for sportsmen are considerably better than in Libya, which does not yet have a boxing federation.

“Boxing is a chance to improve the name of Libya around the world, and show that Libyans are not always fighting with guns,” Mahmoud said. “Like everywhere, we have good and bad people but I would like to put the Libyan flag on the wall for something good, for boxing.”

There is particular poignance to Mahmoud’s new life as a boxing coach. His career was snuffed out in 1979 - the year Gaddafi banned boxing, but any hopes of being able to fight again were dashed when, a few years later, his hands were badly broken during a three-month stint in prison, for daring to claim he was a better sportsman than Gaddafi.

“After I punched one of the prison guards for saying bad things to me and about my mother, he came back with four masked men, who held me down and smashed all my knuckles with a hammer. There was blood everywhere,” he recalls, rubbing his hands, damaged to this day.

Through his work as a coach, Mahmoud has been able to regain some of his pride in the sport. “Gaddafi stopped me boxing for over 30 years but, in just three years I have trained three champions,” he says, adding warmly that all the club’s boxers are champions.

The development of the sport is being held back, however, by a near total lack of support, Mahmoud says. “No one helps us here. The government has given us no money, support, nothing, but still we are fighting, and winning.”

This frustration is felt most keenly by the boxers themselves. “It’s a vicious circle. Because there is no local funding, Libya can’t create a boxing federation but, until it does, it can’t get any international funding, like from the Olympics,” explained boxer Usama Mohamed Maghboub, leaning on the ropes of the scaled-down boxing ring in one corner of the club. A kickboxer for three years, he took up boxing 10 months ago to improve his game. It worked, he said, and the training helped him win a gold medal for Libya in Jordan earlier this year.

Usama said that until either one of Libya’s rival governments puts more funding into boxing, the sport has little chance of being able to support its young boxers. “When I won the gold medal in Jordan, I got just LYD400 (£200) and when I won a Tripoli competition in January, my prize was a pair of trainers that are already worn out,’ he said, flexing his foot to show the holes. “A lot of Libyan sportsmen quit because they have to get jobs to earn money, so they can’t focus properly on training.”

Funding the club themselves, Mahmoud and Sabri Aswad - a former boxer and son of the coach who trained many of Libya’s champions in the 1970s, are determined not to be beaten. Daily training schedules are rigorous and they send fighters to even the smallest local tournaments. Ittihad was the only Tripoli club prepared to travel to Misrata for the third annual Three Cities competition, just days after one of the city’s main checkpoints had been blown up by an Islamic State (IS) suicide bomber.

The tournament was a modest affair, as many of Misrata’s youth are now fighting in Libya’s civil conflict or on the frontline between the city and the IS-occupied town of Sirte.

“We are not in the same position as other cities. We have a war,” explained Muftah Ballowza, head coach of Misrata’s Ahli boxing club - the first of four clubs to open in the city after the revolution. “I had 30 boxers training with me before, but now they are fighting in different places in Libya.” Only two boxers are left, still training at the club, with the rest either injured or still fighting on the front lines.

In the future, when Libya has stabilised, he is convinced that boxing will take a prime position in Libya’s sports scene. “We had a good history of boxing before Gaddafi stopped it and young people like it, so it would grow fast in popularity if there was peace,” he explains. “We hope the war will stop soon. We have lost a lot of people.”

One of the Ahli boxers, 24-year-old Mohamed Sharief, is just back from the frontline. “I was boxing for two years but I need more training now to get back to the same standard as I was before I went to war,” he said. Inspired from a young age by Briton Naseem Hamed, boxing is Mohamed’s passion and he was back at the club within days of returning to his city. “I feel as though my spirit has come back to me,” he said. “I hope to become the best here and, one day, to box in Europe.”

Back in Tripoli, the turnout for the Three Cities tournament was much more modest than for the last competition, held in the capital six months ago. And there is no fight for Usama, whose reputation means that other boxers are too scared to face up to him in the ring. He has already outgrown the Libyan boxing scene and says the only way he can perfect his game now is to train and fight with those better than him, conscious that his first battle is to get the support he needs from his own country.

“My dream is to fight in a world championship or in the Olympics, and win a gold medal,” Usama said. “I am still determined to train and fight outside Libya, even though all the odds are against me.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].