Permanent traumatic stress disorder in Gaza

In a July Haaretz article commemorating the first anniversary of Israel’s Operation Protective Edge, which killed more than 2,250 Palestinians in the Gaza Strip in 51 days, journalist Khaled Diab quotes Palestinian psychologist Hasan Zeyada of the Gaza Community Mental Health Programme: “Gaza has endured multiple losses – what we call multi-traumatic losses. People in other places usually endure a single loss: the loss of a home, or a family member, or a job. Many Gazans have lost them all.”

And while Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is often the focus of discussions of the psychological repercussions of conflict, Diab summarises the observation by various experts that “talk of post- or pre-trauma is futile, since trauma is constant and ongoing”.

In addition to attending professionally to the victims of this Israeli-induced brand of eternal trauma, Dr. Zeyada is personally well acquainted with the phenomenon. Last August, the New York Times reported on his “challenging new patient: himself”. Six of the psychologist’s close family members, including his mother, had just been wiped out by an Israeli airstrike.

Operation Protective Edge came to an end on 26 August 2014. But the diagnosis of collective psychological suffering in the Palestinian coastal enclave is open-ended, and serves to compound the more tangible suffering that attends the regular Israeli release of large quantities of ordnance in the direction of human bodies.

Meanwhile, the concentrated mental and physical battering inflicted upon the population of the Gaza Strip can in itself be seen as a form of psychological warfare, designed to forcibly erode the Palestinian identity and the will of the Palestinians to exist as such.

Israel and its international fan club like to jabber on about ostensible Israeli efforts to avoid civilian casualties during military assaults, with much ado made about phone calls placed to Palestinian phones and leaflets dropped warning residents to flee targeted areas. But the problems with this line of defence are many.

For one thing, such warnings are often not forthcoming, as in the case of Dr. Zeyada’s own family. For another, Israel has never demonstrated much reluctance to fatally bomb civilians - including children - whom Israel itself has instructed to evacuate their homes.

Other issues include the fact that it’s simply not clear where people are supposed to go in such a diminutive and densely populated territory, most of whose residents aren’t allowed out in any direction. The Israeli tradition of bombing schools and hospitals helps ensure that no safe space remains in Gaza - a reality that lends itself to neither physical nor mental stability.

Indeed, Israel’s targeting of the very foundations of Palestinian society is fundamentally at odds with the stated aim of avoiding civilian casualties. And those civilians who manage to avoid physical annihilation find it even harder to avoid the psychological casualty list.

A 15 February UNICEF dispatch, titled “Six months after ceasefire, children of Gaza are trapped in trauma,” recounts the story of two young Palestinian girls whose father was killed when an Israeli artillery shell hit the United Nations-run school where the family had sought refuge. The girls were wounded by shrapnel, and their house was destroyed.

After Protective Edge had run its course, one of the girls refused for months to return to class. Her mother explains: “My children were injured in a school. They saw people injured with missing hands or legs, with wounded faces and eyes. They saw [their] father killed. They no longer see school as a safe place.”

The UNICEF article notes that a good many children in Gaza “need both psychosocial and educational support to resume their lives” but that at least 281 schools were damaged in last year’s operation. “Adding to the difficulty of the situation,” the article says, “teachers themselves suffer from distress.”

Forget the old question of who will guard the guards. Who will care for the caregivers of Gaza, like Dr. Zeyada, or the educators and other folks who might under radically different circumstances be seen as curators of healthy societies? In the end, no one in the territory is immune from Israel’s debilitating predations.

According to the New York Times piece on Dr. Zeyada’s conversion from trauma counsellor to trauma victim, he had confessed that “sometimes… he was troubled by the ethics of treating people who were likely to be traumatised again”. Regarding this troubling position, the psychologist is quoted as follows: “You are like a prison doctor treating a victim of torture, making the prisoner healthy to be interrogated and tortured again.”

It’s not merely because the Gaza Strip has been categorised as “the world’s largest open-air prison” that Dr. Zeyada’s metaphor hits home. It’s also because being Palestinian in Gaza - existing, more or less, in a permanent state of traumatic stress - often amounts to psychological torture.

- Belen Fernandez is the author of The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work, published by Verso. She is a contributing editor at Jacobin magazine.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

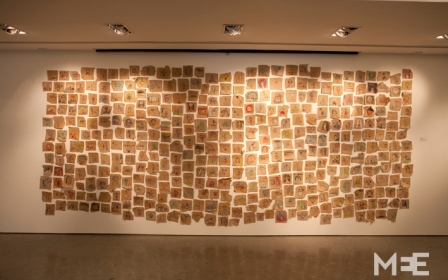

Photo: Palestinian children stand amid the rubble of their partially rebuilt house, on 11 May, 2015, destroyed during the 50-day war in the summer of 2014, in the Eastern Gaza City Shujaiya (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].